How Europe’s Next War Could Start in the Balkans — @RealLifeLore

@RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Geopolitical Unrest: Azerbaijan’s Offensive, Kosovo’s Struggle, and Serbia’s Response | 0:00:00-0:05:20

- Presence of NATO peacekeeping troops in the Western Balkans and the potential for conflict escalation | 0:05:20-0:08:00

- Former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and its Six Republics | 0:08:00-0:09:40

- Legacy of Conflict: Serb-Majority Regions in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina | 0:09:40-0:19:20

- Kosovo’s Independence and Recognition | 0:19:20-0:26:40

- Unraveling the Balkans: Ethnic Cleansing, Secession, and Regional Instability | 0:26:40-0:33:00

- Complex Situation in the Western Balkans | 0:33:00-0:39:00

- Consequences of Redrawing Borders in the Balkans | 0:41:00-10:09:33

https://youtu.be/xV04wSfa4Zs

Geopolitical Unrest: Azerbaijan’s Offensive, Kosovo’s Struggle, and Serbia’s Response | 0:00:00-0:05:20

In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched a military offensive against Artsakh, a region that had declared de facto independence but was considered a province of Azerbaijan by the international community. Within 24 hours, Azerbaijan achieved a decisive victory, leading to the defeat of the separatist ethnic Armenian government. The government agreed to dissolve, and Azerbaijan’s authority was restored over the entire claimed territory. Concerns about ethnic cleansing arose as the Azerbaijani military took control of the region.

Virtually the entirety of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian population, some 100,000 people, fled the area westwards towards the Armenian nation-state, and hardly a single word of condemnation was uttered by anyone in the international community. After all, despite its unilateral declaration of independence and ethnic Armenian majority population, Nagorno-Karabakh was always recognized by every other country in the world as rightful Azerbaijani territory. And what Azerbaijan did in its own territory, even if it looked like an ethnic conflict, was not considered by most outsiders to be a big cause for concern.

But perhaps after witnessing how rapidly Azerbaijan recaptured Nagorno-Karabakh within those 24 hours, and after seeing how little they were even condemned or punished for it after the entire Armenian population fled for their lives, the government of another country with the territory they regard as being an open rebellion felt emboldened to become the next ones to act. Just three days after Azerbaijani forces secured their final control over Nagorno-Karabakh, a group of 30 heavily armed Serb paramilitary militants suddenly appeared in the town of Banjska in the northern reaches of Kosovo and began blockading a road there. The Kosovo police force responded and a deadly gunfight erupted, in front of the government in Belgrade. Nonetheless, Serbia’s government hailed the attack as a form of legitimate resistance by the supposedly oppressed ethnic Serbs in northern Kosovo, and blamed the Kosovo government for having escalated the situation in the area to the point of having caused the deadly gunfight. You see, the geopolitical situation in northern Kosovo has been complex for some time. Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence from Serbia back in 2008, which the Serbian government to date has never recognized as legitimate. Serbia therefore continues to officially assert that Kosovo still belongs entirely to Serbia, and effectively considers it as a Serbian province in open rebellion.

But Kosovo is overall very ethnically and religiously distinct from Serbia. Roughly 93% of Kosovo’s nearly 2 million people today are ethnic Albanians who largely follow the Islamic faith and who represent the territory’s overwhelming majority. However, there is still a substantial ethnic Serb minority in Kosovo as well, who largely follow Orthodox Christianity and represent around 6.5% of the overall population, though they’re largely inclined to consider finally recognizing Kosovo’s independence. The Kosovo government has continually dragged its feet on this issue and has never agreed to do so. The issue finally came to a boiling point in April of 2023, when Kosovo hosted municipal elections that the ethnic Serbs in northern Kosovo overwhelmingly boycotted in protest over the lack of their autonomy being granted. This led to an abysmal 3.5% voter turnout in the north, resulting in the election of ethnic Albanian mayors to govern over the ethnic Serbs.

When the Kosovo security forces then attempted to escort these Albanian mayors into their government offices in the Serb-majority north, the Kosovar Serbs began organizing widescale protests that escalated in violence and injured dozens, ultimately culminating with the armed Serb attack in northern Kosovo that killed four. In the immediate aftermath of that attack and Kosovo’s accusations that the Serbian government itself was responsible, the Serbian army began what the United States referred to as a completely unprecedented military buildup along their entire southern border with Kosovo, surging enough troops into the area to roughly double their numbers, up to roughly 8,400 strong. This situation was described by the United States as the largest Serbian military buildup on Kosovo’s border since Kosovo declared its independence in 2008.

Presence of NATO peacekeeping troops in the Western Balkans and the potential for conflict escalation | 0:05:20-0:08:00

After Kosovo declared independence, the situation seemed eerily similar to Washington’s previous warnings of Russia’s military buildup on Ukraine’s borders leading up to their February invasion. The difference was an additional presence of around 4,500 NATO peacekeeping troops in the country. These troops would likely be caught in the line of fire and could potentially draw the rest of the NATO alliance directly into the war. Since NATO currently surrounds Serbia on virtually all of its sides, Serbia knows that it would quickly lose if NATO were to get involved. Therefore, after Serbia began building up its troops on the border, the United States warned that Serbia would immediately suffer devastating consequences if it were to escalate the situation any further, while NATO quickly announced a troop surge of its own into Kosovo with around a thousand additional deployed peacekeepers.

Serbia’s nationalist and increasingly autocratic and revisionist President, Aleksandar Vučić, blinked first. Serbian troops and their equipment began withdrawing from the Kosovo border, and troop levels were brought back down to more historically normal levels, and the immediate crisis fizzled out. However, at the same time, tensions have also been rising again in nearby Bosnia and Herzegovina. A deeply sectarian and ethnically divided country, where the current leader of the ethnically Serb majority Republika Srpska has repeatedly threatened to secede his territory from the country and join with Serbia. This has been a long-time goal of many Bosnian Serbs since the 1990s, who represent around 31% of the country’s population today and control around half of the country’s territory. While the United States champions the ethnic Albanians, they have urged Republika Srpska to halt the talk on secession or face consequences. After Serbia’s military buildup on Kosovo’s border, the United States authorized the sale of $75 million worth of Javelin anti-tank weapons to the Kosovo security forces so that they can better defend themselves against a possible future Serbian invasion. This development deeply disappointed the Serbian government. Still today, in the 2020s, the Western Balkans continue to be Europe’s more traditional powder keg that has the potential to explode in another violent conflict in the future if the region’s leaders and outside powers aren’t careful enough. This situation is no doubt being encouraged to happen by outside influences like Russia to continue distracting the world from the war in Ukraine.

The Balkans as a whole have infamously been among the most chronically unstable and chaotic regions in Europe for centuries. But to understand the current unstable geopolitical fault lines that run through here, and the risk of war that the status of Kosovo and/or Bosnia could ultimately trigger today, we only need to go back to the recent events of the 1990s during the collapse of the former Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was a complex, multi-ethnic state that existed across most of the 20th century, but by the time of its collapse, it was administratively composed of six largely autonomous socialist republics.

Former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and its Six Republics | 0:08:00-0:09:40

The former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia consisted of six republics: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Serbia. Serbia contained two largely autonomous provinces, Vojvodina in the north and Kosovo in the south. The administrative boundaries were based on distinct ethnic and sectarian groups, including Slovenes, Croats, Bosniaks, Albanians, Serbs, Montenegrins, and Macedonians. However, these divisions did not perfectly align with geographic realities, leading to mixed populations in various regions. For example, there were large numbers of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia, and Serbs in Kosovo, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia.

Yugoslavia’s collapse in the early 1990s led to a series of inter-ethnic and sectarian wars as different ethnicities fought to remain united and free from domination in a post-Yugoslavia world.

Legacy of Conflict: Serb-Majority Regions in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina | 0:09:40-0:19:20

The conflicts in the Serb-majority parts of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina led to secessions and desires for annexation into greater Serbia and Croatia. Wars in the 1990s resulted in over 120,000 deaths and the displacement of millions. Croatian Serbs attempted ethnic cleansing but were defeated by the Croatian government. In Bosnia, a civil war involving Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs ended in 1995 with NATO intervention and the Dayton Peace Accords. Bosnia and Herzegovina became a decentralized state with two autonomous entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska.

The Bosnian Serbs dominate Bosnia with a shared district controlled jointly with another entity. Republika Srpska carried out ethnic cleansing, altering the demographics. The Bosnian constitution is Annex 4 of the Dayton Peace Accords, drafted by the US, preventing secession attempts. The High Representative, appointed internationally, enforces peace and has wide-sweeping powers in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been likened to a colonial Viceroy, overseeing an internationally governed protectorate to maintain peace and prevent further conflict. NATO deployed 60,000 soldiers as peacekeepers to support the High Representative’s authority.

Following the wars in Bosnia and Croatia, a conflict erupted in Kosovo in 1998, despite the Dayton Peace Agreement leaving Kosovo as part of Serbia. The ethnic Albanian majority of Kosovo initiated an armed insurgency against the Serbian government in the name of either independence or union with Albania. The Serbs decided to massively retaliate against this insurgency in Kosovo by sending in tens of thousands of soldiers and police to harshly repress the entire Albanian population. More than 2,000 Albanians in Kosovo were killed, and by March of 1999, the Serbs began initiating a full-scale campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo in a literal attempt to forcibly expel the entire Albanian population from the country. Around 860,000 Kosovar Albanians were forcibly expelled from their homes in Kosovo and pushed out of the country by the Serbian army and police.

This led to NATO demanding that the Serbian army immediately leave Kosovo, halt their operations, and allow tens of thousands of NATO peacekeepers into the country to restore peace. After Serbia refused, NATO went to the United Nations again, just like they did with Bosnia back in 1995, to request legal approval for another armed intervention to defend Kosovo.

But this time, Russia and China each threatened to use their status as permanent members of the United Nations Security Council to veto the authorization, and so no UN approval was ever granted. Nonetheless, NATO decided to militarily intervene against Serbia in 1999 without the UN’s approval anyway, under the argument that doing so was a humanitarian imperative to prevent the total ethnic cleansing of the 1.5 million Albanians who lived in Kosovo. And while the intervention might not have been technically legal under international law, NATO argued that it was still fully justified and legitimate anyway under these humanitarian circumstances.

For two and a half months with unchallenged air superiority, NATO warplanes relentlessly bombarded Serbian military targets and civilian infrastructure all across the country in an attempt to cripple the country’s ability to wage war in Kosovo. The NATO air campaign killed more than a thousand Serbian soldiers and police and wounded more than 5,000 others. It also resulted in the deaths of several hundred civilians and the destruction of several hundred Serbian tanks and aircraft, while only suffering minimal losses of their own, including the shootdown of an F-117 Nighthawk, the first loss of a stealth aircraft due to combat in the history of warfare. By June of 1999, the Serbian Armed Forces had been crippled by NATO’s largely unchallenged aerial attacks. Later, in 2015, the Serbian government self-calculated that the NATO bombing campaign had resulted in economic losses to Serbia of approximately $29.6 billion. After more than 13,400 deaths caused by the Kosovo War between 1998 and 1999, which also saw approximately 90% of the 1.5 million ethnic Albanian population of Kosovo displaced and turned into refugees, the Serbian army and police agreed to withdraw from Kosovo. Subsequently, 50,000 NATO ground troops immediately moved into Kosovo to replace them.

With the stated mission of retaining peace and facilitating the return of the estimated 860,000 Albanians who had been forcibly expelled beyond Kosovo, most of the Albanian population returned to Kosovo after the war. However, more than half of the ethnically Serb population in Kosovo either fled or were forcibly expelled themselves into Serbia, dramatically reducing the Serb population in Kosovo from around 200,000 people to fewer than 100,000 remaining today, largely concentrated in the north. To continue protecting the Kosovar Albanian population from the Serbs who had attempted to ethnically cleanse them, a UN interim administration was established as Kosovo’s new de facto government.

While NATO forces remained on the ground to guard the territory, known as the Kosovo Force or KFOR, a contingent of NATO troops has permanently remained there to this day. Regardless of NATO’s intentions, intervening against Serbia and protecting Kosovo in 1999 set a number of major international legal precedents that have carried consequences ever since. Serbia did not attack NATO first, and Kosovo, up to that point, was universally recognized internationally as a territory belonging to Serbia. NATO, originally founded as a strictly defensive military alliance, intended to go to war only if one of its member states were attacked by an outsider first. However, NATO attacked and bombed a country that had not actually attacked them first, and they did it without the legal approval of the United Nations. Many outside countries took note of this precedent set by NATO, especially Russia, which afterwards became convinced that NATO was not actually the strictly defensive military alliance it claimed to be.

Russian foreign policy grew increasingly paranoid that if NATO attacked Serbia on the grounds of a humanitarian intervention, it might do the same to other countries, such as Ukraine, which Russia never wanted to see within NATO. The wars across the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s collectively killed more than 140,000 people, displaced millions more, and created the modern ethnic and political borders in the Balkans that we know today, with only moderate changes being made to them since then. In 2006, Montenegro hosted a referendum on independence from Serbia that was narrowly approved by just over 55% of voters, leading Montenegro to declare its independence from Serbia.

Kosovo’s Independence and Recognition | 0:19:20-0:26:40

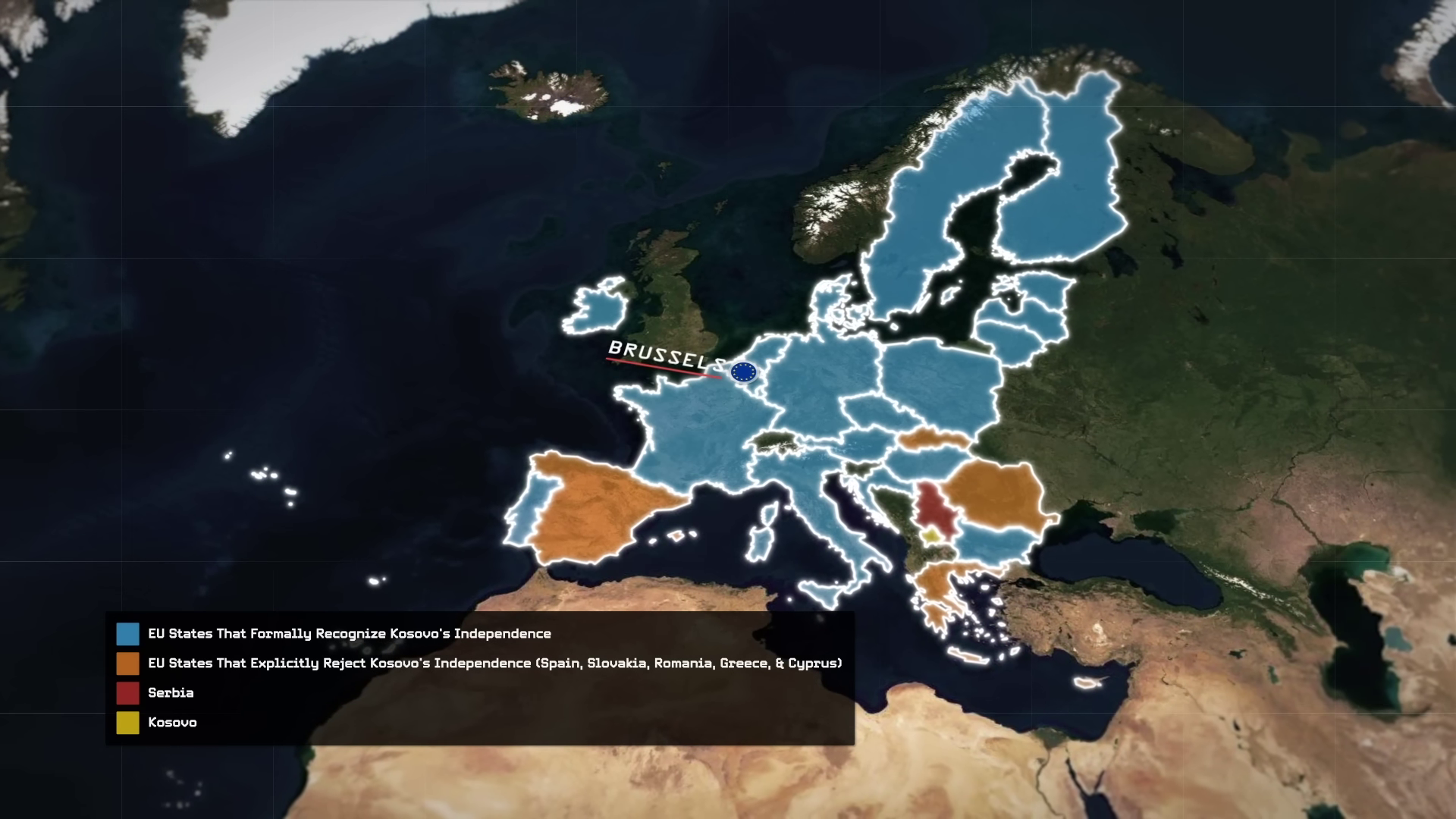

Kosovo’s independence was recognized by the government in Belgrade as a legitimate expression of self-determination, leading to Serbia becoming landlocked. However, only 102 out of 193 UN member states recognize Kosovo’s independence, with concerns about setting a precedent for other territorial disputes and independence movements globally.

While the vast majority of countries in both the European Union and NATO have chosen to recognize Kosovo’s independence, five notable exceptions in this bloc continue to staunchly reject it: Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain. All of them fear what precedent would be set by recognizing Kosovo. Cyprus and, by extension, Greece each fear that recognizing Kosovo’s unilateral secession from Serbia would carry legal implications for the legitimacy of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which similarly unilaterally declared its own secession from Cyprus without the Cypriot government’s permission. Romania fears that recognizing Kosovo’s unilateral secession could have implications for their large ethnic Hungarian minority, which makes up around 6% of the entire Romanian population.

Slovakia has similar concerns about recognizing Kosovo over the precedent it could set for their own large ethnic Hungarian minority, which makes up about 8% of their population and lives across the south. If Romania and Slovakia recognize the Albanians’ right to unilaterally secede from Serbia, Serbia, would the ethnic Hungarians in Romania and Slovakia eventually use the precedent it sets to declare their own unilateral secessions?

For the government in Spain, the biggest fear of recognizing Kosovo’s unilateral independence would be setting a huge precedent for their own large independence movements that are still going on in Catalonia and the Basque Country. China has never and likely will never accept Kosovo’s independence because of the precedent it would carry for Taiwan’s right to unilaterally declare its own independence. Indeed, Kosovo and Taiwan are directly diplomatically linked with each other. Both are considered to be rebellious provinces by larger revisionist powers, and both are militarily and diplomatically supported by the United States against those revisionist powers. Consequently, Kosovo and Taiwan maintain very close diplomatic relations with each other to support one another’s similar cause, while Serbia and China conversely maintain very close diplomatic relations as well to suppress each other’s similar independence movements.

Serbia firmly supports Beijing’s One China policy and Beijing’s claim to Taiwan. Serbia is considered to be China’s strongest ally in Europe, while China firmly supports Serbia’s continued claim to Kosovo and uses its position as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council to block Kosovo’s admission into the United Nations. Both countries stand in firm opposition to unilateral independence movements worldwide.

Perhaps most infamously, Russia saw the precedent of what happened in Kosovo and began immediately applying it to fit its own foreign policy objectives. Russia cited the precedent of NATO troops attacking Serbia in 1999 without the UN’s approval, NATO’s subsequent occupation of Kosovo, and Kosovo’s 2008 unilateral independence declaration from Serbia to justify its own non-UN sanctioned intervention into Georgia mere months later. This culminated in a wide-scale Russian bombing campaign and the Russian occupations of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which each declared their own unilateral secessions from Georgia based on the legal precedent supposedly set first by Kosovo.

The ethnic Russian majority in Crimea would also cite the precedent set by Kosovo in 2008 when they unilaterally declared their own independence from Ukraine in 2014, while in the lead-up to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia and by extension Belarus have never recognized Kosovo’s independence, even though they’ve repeatedly cited the precedent supposedly set by Kosovo to justify their own actions taken in Georgia and in Ukraine. While Georgia, Ukraine, and also Moldova have all conversely never agreed to recognize Kosovo’s independence either, due to the precedent it would set for their own pro-Russian And, besides for the precedent that Kosovo set for Russia’s military interventions in Europe, the other potentially dangerous precedent that it set was very nearby in the seemingly always troubled Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Serb-dominated Republika Srpska within the country immediately grew emboldened after Kosovo’s unilateral secession from Serbia, and their leader, Milorad Dodik, has repeatedly ever since asserted that if the Albanians in Kosovo enjoy the right to self-determination from Serbia, then the Serbs of the Republika Srpska should enjoy the right of self-determination from Bosnia as well.

Within days of Kosovo’s independence declaration, Republika Srpska passed a resolution calling for an independence referendum of their own. If a majority of UN member states ever recognized Kosovo, in 2010, a poll of Bosnian Serbs taken by the Brussels-based Gallup Balkan Monitor found that 87% of them at the time would support the independence referendum being called. So far, though, Milorad Dodik has not yet ever called for this referendum on Republika Srpska’s independence, though he frequently threatened to do so and warned that he will if the Bosnian Serbs’ autonomy and privileged position within Bosnian Herzegovina’s government are ever threatened.

NATO, the United States, and the Peace Implementation Council that has appointed the High Representative to Bosnia ever since the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995 have, conversely, repeatedly insisted that the Republic of Serbska has absolutely no legal right to ever secede from Bosnia. Washington has always taken the argument that Kosovo’s unilateral secession from Serbia was a unique case in modern history that does not set any legal precedent for any other separatist movements anywhere else.

Unraveling the Balkans: Ethnic Cleansing, Secession, and Regional Instability | 0:26:40-0:33:00

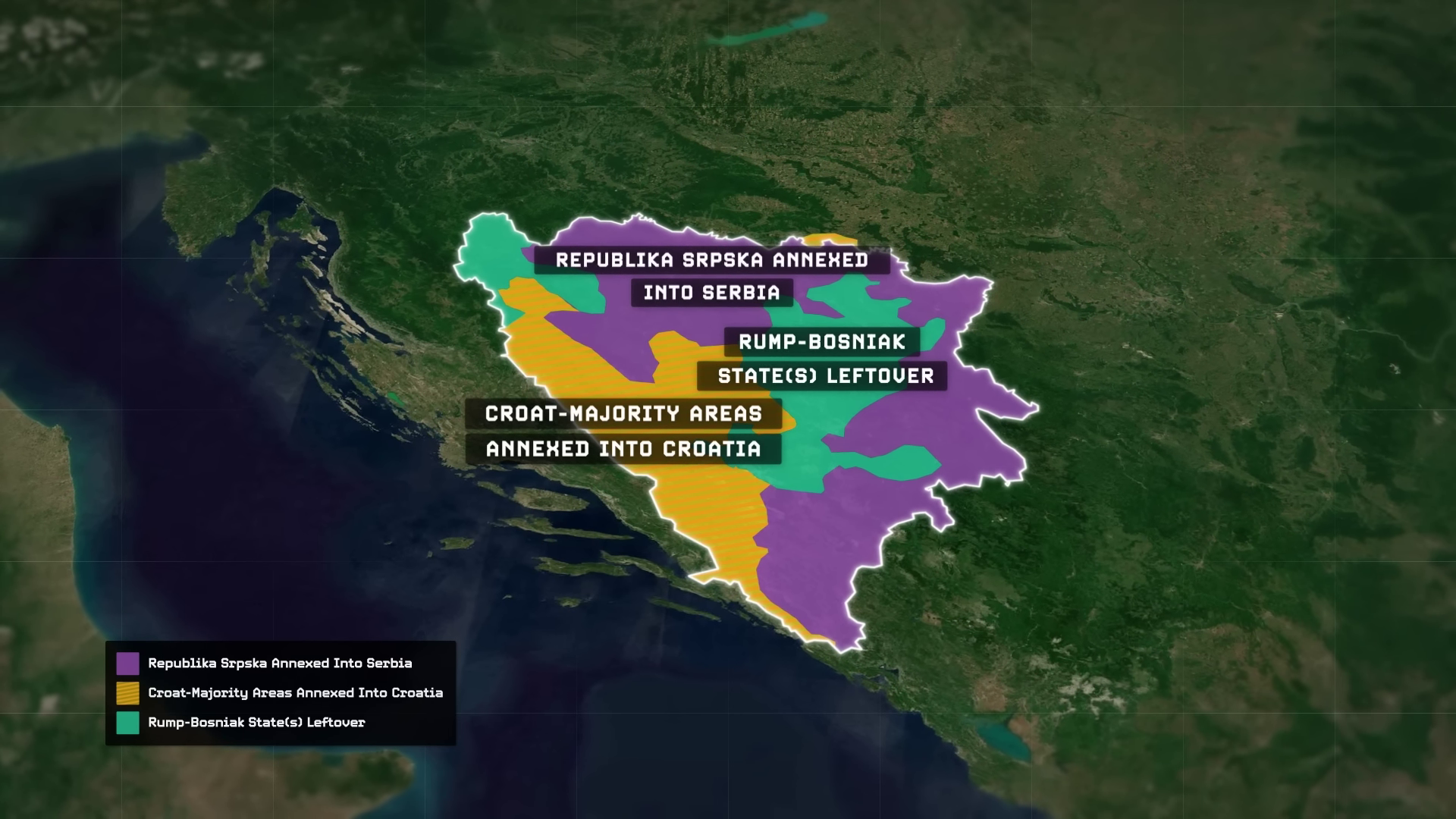

Washington argues that Republika Srpska in Bosnia was created over years as an ethno-state resulting from ethnic cleansing and genocide. The Republika Srpska leaving Bosnia to join Serbia would legitimize ethnic cleansing and genocide. The Dayton Peace Accords prohibit secession, and the US is committed to Bosnia’s territorial integrity. Another secession attempt could lead to war, with Bosnian Serbs taking 49% of the territory despite comprising only 31% of the population.

The Bosnian Serbs massacred over 8,300 mostly Bosniak residents in Srebrenica during the war in the 90s. If the Bosnian Serbs successfully seceded and attempted to join Serbia, it would involve taking territory that includes Srebrenica and connecting their territories in the north and south.

The potential break-off of Bosnian Croats to join Croatia could leave a vulnerable Bosniak state without support, leading to instability and potential conflict in the region. The Bosniaks have no fallback support like the Bosnian Serbs and Croats, relying solely on the international community. The historical context of genocide and ethnic tensions in the region further complicates the situation, with the possibility of a resumption of war if Republika Srpska dissolves the country. The core issue in the Western Balkans stems from the uneven distribution of ethnicities and the desire for national unity beyond borders, leading to ongoing instability and conflict.

There are nearly 7 million ethnic Serbs in the Balkans, with significant populations in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Kosovo. Serbian nationalists believe in extending Serbia’s borders to include Serb-majority territories in neighboring countries. The government of Serbia aims to protect Serbian people wherever they live, including in Republika Srpska and Kosovo. Republika Srpska’s leader, Milorad Dodik, advocates for Serbian reunification and opposes Bosnia’s integration into NATO and the EU. The presence of NATO peacekeeping troops in Bosnia has decreased over the years, with only a small EU force remaining.

Complex Situation in the Western Balkans | 0:33:00-0:39:00

The situation in the Western Balkans is complex, with tensions between different ethnic groups and unresolved disputes, particularly the Kosovo-Serbia conflict. The European Union has been involved in normalization talks between Kosovo and Serbia, with the condition that Serbia recognizes Kosovo’s independence. However, progress has been slow due to nationalist governments in both countries. The region is also influenced by external powers like the United States, Russia, and China. Some countries in the region have joined NATO and the EU, while others, like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Kosovo, have not. Serbia has been working to prevent Bosnia and Kosovo from joining NATO and has maintained a delicate balance between different geopolitical influences. The situation remains tense and unresolved, with potential implications for the stability of the region.

Serbia also became the very first European country to ever purchase and operate Chinese weapon systems, which included four batteries of China’s modern HQ-22 surface-to-air missile system. This only further fueled Western skepticism about Serbia’s ultimate intentions. Has Serbia learned the military lessons it suffered throughout the 1990s, when NATO was able to use its undisputed air superiority over Bosnia, Serbia, and Kosovo to relentlessly bomb Serbian military targets and cities on the ground, forcing their surrender? If another conflict erupts over the future of the Serbs in Bosnia or Kosovo in the future, would NATO reconsider bombing Serbia again if it had advanced Chinese anti-air defense systems this time around? China is more than happy to help Serbia out with this, as it not only gives them a military footprint in Europe, but the memory is still fresh in Beijing that back in 1999, during NATO’s bombing campaign of Serbia, NATO forces accidentally bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese journalists and injuring more than a dozen others. Providing the Serbs with their own anti-air defenses now in the 2020s is a direct message from both Beijing and Belgrade that they still haven’t forgotten about that.

The government has made it clear that they will only consider agreeing to recognize Kosovo’s independence under one of two possible scenarios. One, Kosovo grants the ethnic Serbs in the north of the country their full autonomy, which they seemingly and perhaps understandably aren’t willing to do. Or, option two, and perhaps the one that’s actually more preferable to both Serbia and Kosovo alike, they both agree on a territorial and population exchange treaty in which the borders of the Balkans would be redrawn. Kosovo would cede their northern Serb-majority areas to Serbia, while in exchange, Serbia would cede their southern Albanian-majority areas to Kosovo, and Serbia would finally recognize Kosovo’s independence. This would leave Kosovo more ethnically homogeneous and a more functioning state without a large and autonomous Serb minority. This would also free up Kosovo to finally join the UN, the EU, and even NATO if they wished, or to potentially even unify with the Albanian nation-state, assuming that Albania would accept them, which isn’t a given.

Consequences of Redrawing Borders in the Balkans | 0:41:00-10:09:33

In the closing days of the previous Trump administration in Washington, rumors swirled that Trump was prepared to greenlight America’s authorizations for this exact kind of deal, which would almost certainly have opened up another dangerous Pandora’s box in Europe, much like Kosovo’s initial declaration of independence did back in 2008, with potentially just as unforeseen and catastrophic consequences.

While the territorial and population exchange agreement is likely the simplest and most straightforward solution to finally solving the Serbia-Kosovo question, such a deal would also immediately legitimize territorial exchanges in Europe in the 21st century, with explicit United States approval. The deal fell apart after Trump lost the 2020 election, and the incoming Biden administration has remained focused on pressuring Kosovo to accept the option of autonomy for their northern Serb subjects instead. However, Serbia’s nationalist president, Aleksandar Vucic, may simply be holding out and gambling for Trump to return to the White House in the upcoming November election. If Trump does return, then his deal for the territorial exchange between Serbia and Kosovo may resurface, and if it happens, the precedent would be profound.

The leaders of the Republika Srpska in Bosnia would almost certainly immediately pounce on the precedent of the Serbs in Kosovo being legally annexed into Serbia with America’s approval, and the further potential annexation of all of Kosovo into Albania. They would begin agitating even more than they already have been for their own secession from Bosnia and annexation into Serbia as well. However, while the logic of territorial exchange could work through peaceful means between Kosovo and Serbia, it would also immediately mean war in Bosnia. If the Republika Srpska seized on the precedent, finally hosted their own referendum on independence, continued to reject the authority of the internationally appointed High Representative, and actually declared their own secession, who would actually intervene and stop them from leaving other than probably the Bosniaks?

Would a return of the Trump administration to the White House, openly skeptical of NATO as an institution and potentially authorizing Serbian secession in Kosovo, actually lead to another major NATO charge into Bosnia to prevent the Bosnian Serbs from also seceding? If America didn’t respond, there could be potential consequences of redrawing borders and exchanging territories in the Balkans. The region is fraught with complex ethnic and geopolitical dynamics, with a possibility of renewed conflicts and tensions, similar to past conflicts in the Western Balkans, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. There is a delicate balance of ethnic groups in the region, and altering borders could lead to cascading consequences.