Why Ethiopia is Preparing to Invade Eritrea Next — @RealLifeLore

@RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Challenges of Ethiopia’s Landlocked Position | 0:00:00-0:02:00

- Ethiopia’s Trade Volume and Need for Ocean Access | 0:02:00-0:06:00

- Ethiopia’s History and Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity | 0:06:00-0:09:00

- Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity in Ethiopia | 0:09:20-0:11:20

- Ethiopia’s Modern Conflicts | 0:11:20-0:18:40

- The Ethiopian Famine and Political Changes in the 1990s | 0:18:40-0:22:00

- The Frozen Conflict Between Ethiopia and Eritrea: A Timeline of Events | 0:22:00-0:28:20

- Efforts to Make Peace with Eritrea | 0:28:20-0:33:40

- Ethiopia’s Struggle for Port Access and Naval Ambitions | 0:33:40-0:39:20

- Potential Consequences of Launching a War Against Eritrea for Ethiopia | 0:39:20-

https://youtu.be/J-hABbIseGk

Challenges of Ethiopia’s Landlocked Position | 0:00:00-0:02:00

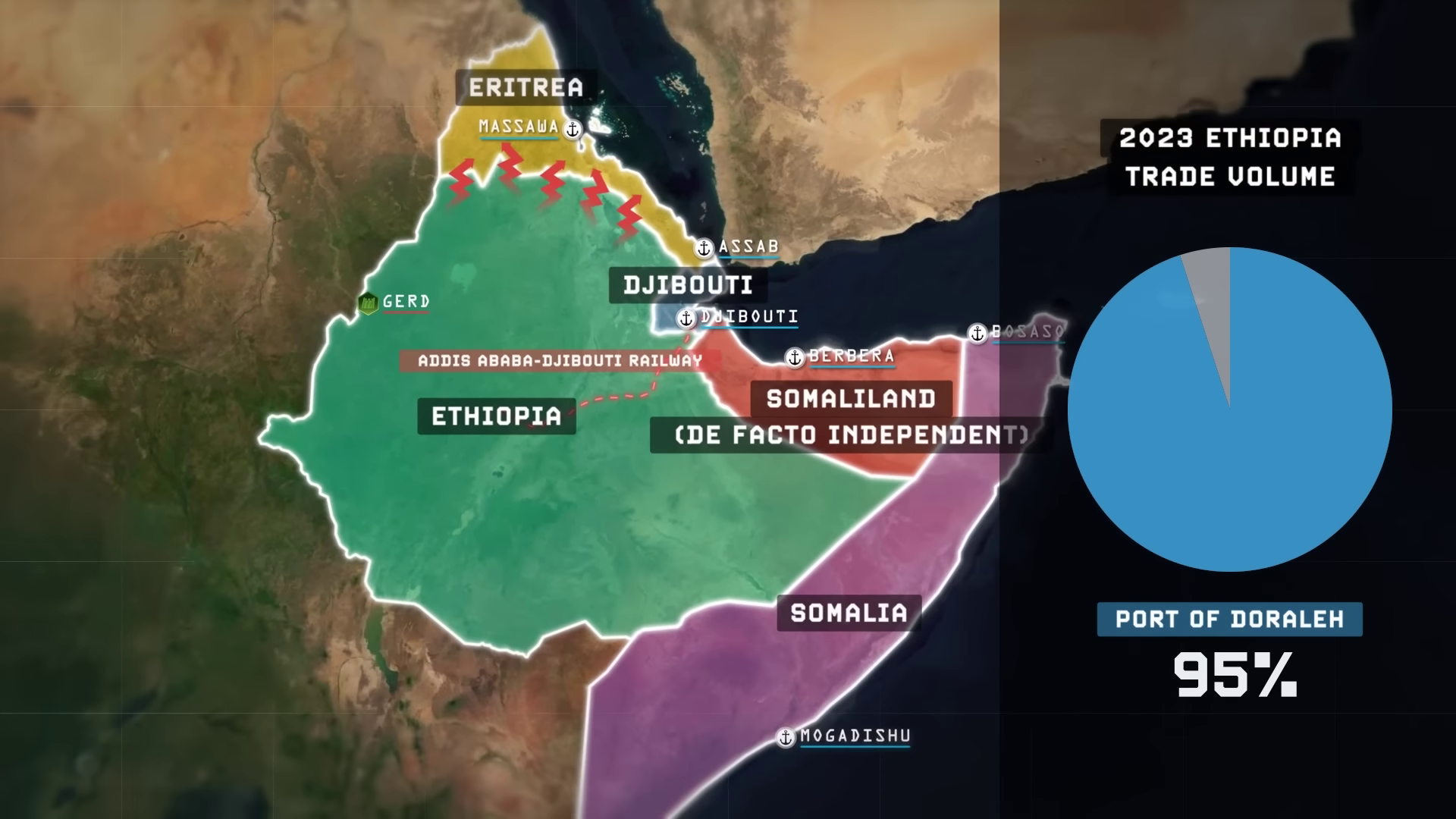

First elected to the office in 2018, Abiy Ahmed has found himself as the leader of an nation with both tremendous potential and tremendous vulnerabilities. With a population of 126.5 million people as of 2023, Ethiopia is the second most populous country on the African continent, and by far the most populous one in East Africa, with a population that is roughly equivalent to every single one of its geographic neighbors combined, and a population that is continuing to grow very rapidly. By the end of this decade in 2030, the Ethiopian population is projected to grow to as many as 150 million people, which will make Ethiopia the 9th most heavily populated country in the world by then, with even more people than Russia. But uniquely, out of all the countries in the world that will be in the top 10, 10 most populous states by 2030, only Ethiopia among them will be completely landlocked without any direct access to the global ocean. In fact, out of the top 33 largest countries in the world today by population, Ethiopia is the only one among them who is landlocked. The next most populous landlocked countries after Ethiopia are Uganda and Uzbekistan, and they only have a fraction of the same population that Ethiopia does. Obviously, this lack of direct access to the sea is a serious limitation on the ability for Ethiopia to conduct trade with the rest of the world, as all of Ethiopia’s imports and exports must each flow through other countries that surround it first. These countries can leverage their geographic position over Ethiopia in the form of charging taxes, tolls, and fees on allowing that trade to pass through them. Right now, an overwhelming 95% of Ethiopia’s entire trade volume, consisting of both imports and exports, flows exclusively through the deep water line to trade with the outside world, and its single most important logistical artery. But it hasn’t come very cheap for them.

Ethiopia’s Trade Volume and Need for Ocean Access | 0:02:00-0:06:00

Ethiopia’s trade volume with Djibouti accounts for 70% of the port’s commercial activity, generating over a billion dollars in annual port fees. This amount is significant, representing a quarter of Djibouti’s GDP. Despite concerns about dependency and humanitarian aid in Ethiopia, the port of Andorra in Djibouti remains safe for Ethiopian use, surrounded by military bases of major powers like China, the US, France, Japan, and Italy. Ethiopia’s fear is not about physical attacks on its port access in Djibouti.

Ethiopia is vulnerable because the railroad connecting it to the port has the potential for rebel attacks. The Ethiopian Prime Minister has remarked on the country’s geographic isolation and the need for access to the ocean. This has created tensions with neighboring countries like Eritrea, Somalia, and Djibouti. Ethiopian troop buildup and aggressive comments on their landlocked status have created the potential for conflict to escalate in the region.

Ethiopia’s History and Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity | 0:06:00-0:09:00

Ethiopia, an ancient civilization dating back to the 3rd century, has a vast history of military campaigns, including the successful repelling of two attempted foreign conquests by the Egyptians and Italians. The country's geographically challenging terrain has made it difficult for invaders to conquer and occupy, ensuring its unyielding resistance to European colonialism. Addis Ababa, the capital city, is situated at a high elevation and surrounded by varied landscapes. Over time, this geographical diversity has led to ethnic diversity, which has subsequently posed challenges in maintaining national unity.

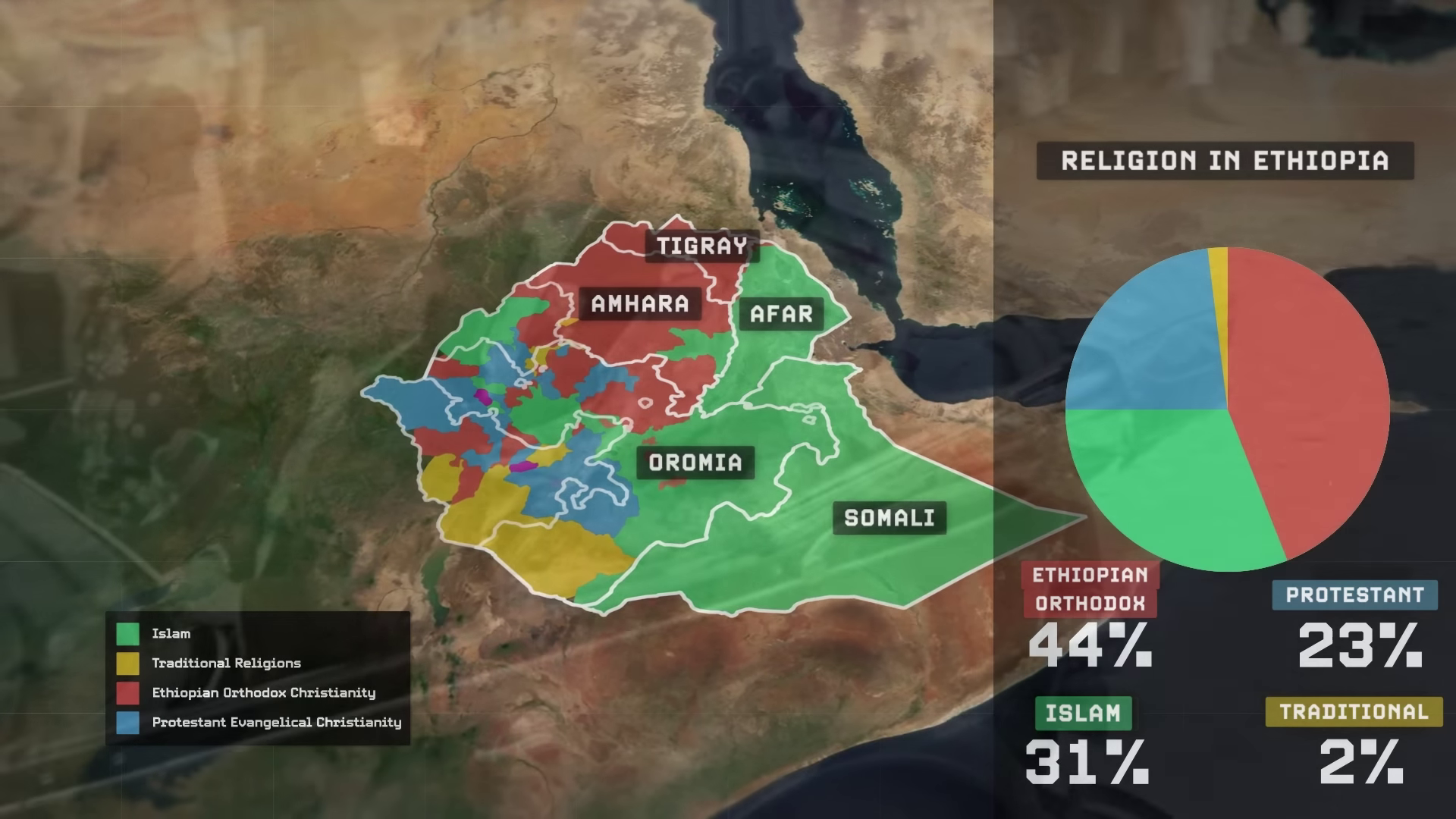

Ethiopia is a home to nine major ethnic groups and more than eighty distinct languages from different linguistic families. The Amhara ethnic group ruled the imperial period, leaving the Amharic language as the primary lingua franca in the country. However, the Amharas only constitute about 27% of the total population, with the Oromos making up the largest group. The country is also notably religiously diverse, being one of the first to adopt Christianity in the 4th century AD.

Different ethnic groups in Ethiopia follow either Christianity or Islam. The contrasting religious followings have historically created a sense of separateness between the Amhara Christians in the highlands and the primarily Muslim populations in other parts of the country. Ethiopia's last emperor, Halle Selassie, was an Amharic Orthodox Christian who ascended to the throne in 1930.

Ethiopia’s Modern Conflicts | 0:11:20-0:18:40

In the 1930s, Italy overran Ethiopia using heavy artillery, airplanes, and chemical weapons. The Emperor fled to Britain in exile, and Italy merged conquered Ethiopia with Eritrea and Somalia to form Italian East Africa. In 1940, Italy entered World War II, conquered British Somaliland, and added it to Italian East Africa.

The British later invaded the area in 1941. Ethiopia regained independence in 1960 and merged with British Somaliland to form Somalia. Eritrea faced controversy post-World War II, with debates on its future control between Italy, the Soviets, Eritreans, and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. This situation also had the potential to break Ethiopia out of its landlocked status and give it a direct coastline on the Red Sea.

As an absolute monarchy, Haile Selassie’s regime in Ethiopia staunchly opposed the spread of communism and the Soviet Union, making him a natural ally for the Americans in the following Cold War. The Americans decided to support his view that Eritrea should be given to Ethiopia.

At Washington’s insistence, the United Nations passed Resolution 390A in December of 1950, which went into effect two years later in 1952, joining Eritrea with Ethiopia in a newly created country called the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea. In this federation, Eritrea was supposed to possess a very high degree of autonomy separate from Ethiopia, with its own flag, police force, control over its administration, taxes, and so on. However, the Ethiopian emperor spent the following years continually whittling away at this autonomy. He eventually imposed the Amharic language of Ethiopia as the sole official language upon Eritrea, replacing the indigenous Arabic and Tigrayan languages, which sparked a full-blown armed independence movement in Eritrea that rose up against him in 1961.

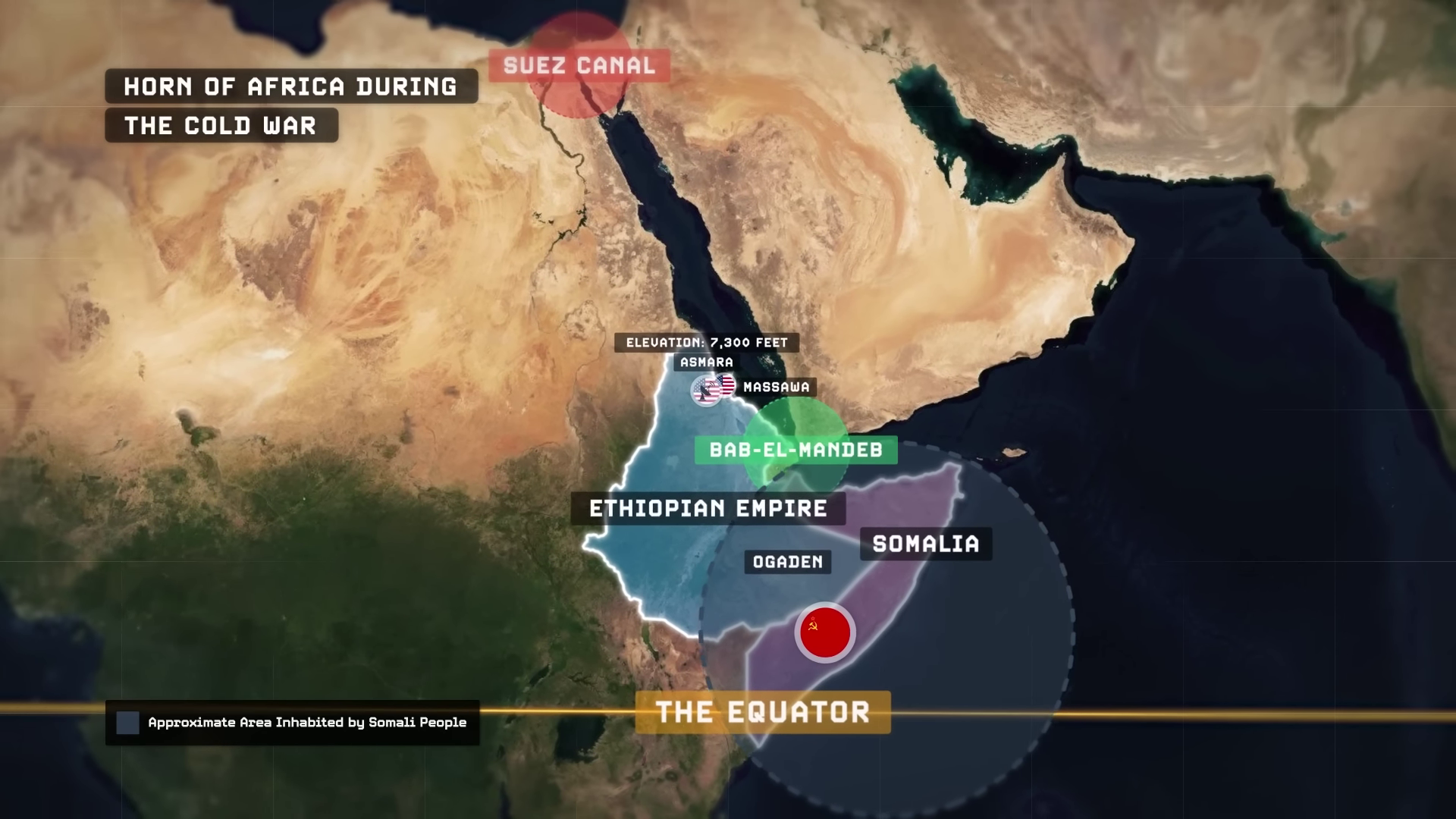

In 1962, Haile Selassie declared that the Federation of Ethiopian Eritrea was formally abolished, and the Ethiopian Empire was simply annexing all of Eritrea outright, a development that did not sit very well with most Eritreans. Armed Eritrean insurgents and guerrillas rose up and continued to fight against the Ethiopian state for their independence for decades. In the meantime, the lines of the Cold War deepened around Ethiopia’s neighborhood. To reward the United States for supporting Ethiopia’s annexation of Eritrea, Haile Selassie granted the Americans the right to establish a naval base on the coast of Massawa, between the strategic Suez Canal in the north and the narrow Bab el-Mandeb strait in the south, along with a vast radio antenna farm in the Eritrean capital of Asmara nearby, a geographically ideal location to place one due to its proximity to the Middle East and the equator, and its high altitude at 7,300 feet above sea level.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union initially chose to counter America’s close relationship with the Ethiopian Empire by supporting their biggest regional rival, Somalia, a nation that laid claim to the ethnically Somali majority area of eastern Ethiopia in a region known as the Ogaden, in pursuit of a foreign policy in Mogadishu to establish a greater Somalia, out of all the ethnically Somali majority areas in the Horn of Africa.

After emerging as the leader of the only country in Africa that had stayed off European colonialism, Haile Selassie also carried a lot of diplomatic clout on the continent during the decolonization era of the 1960s, which led to him successfully arguing that the new Organization of African Unity should have its headquarters established in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa in 1963.

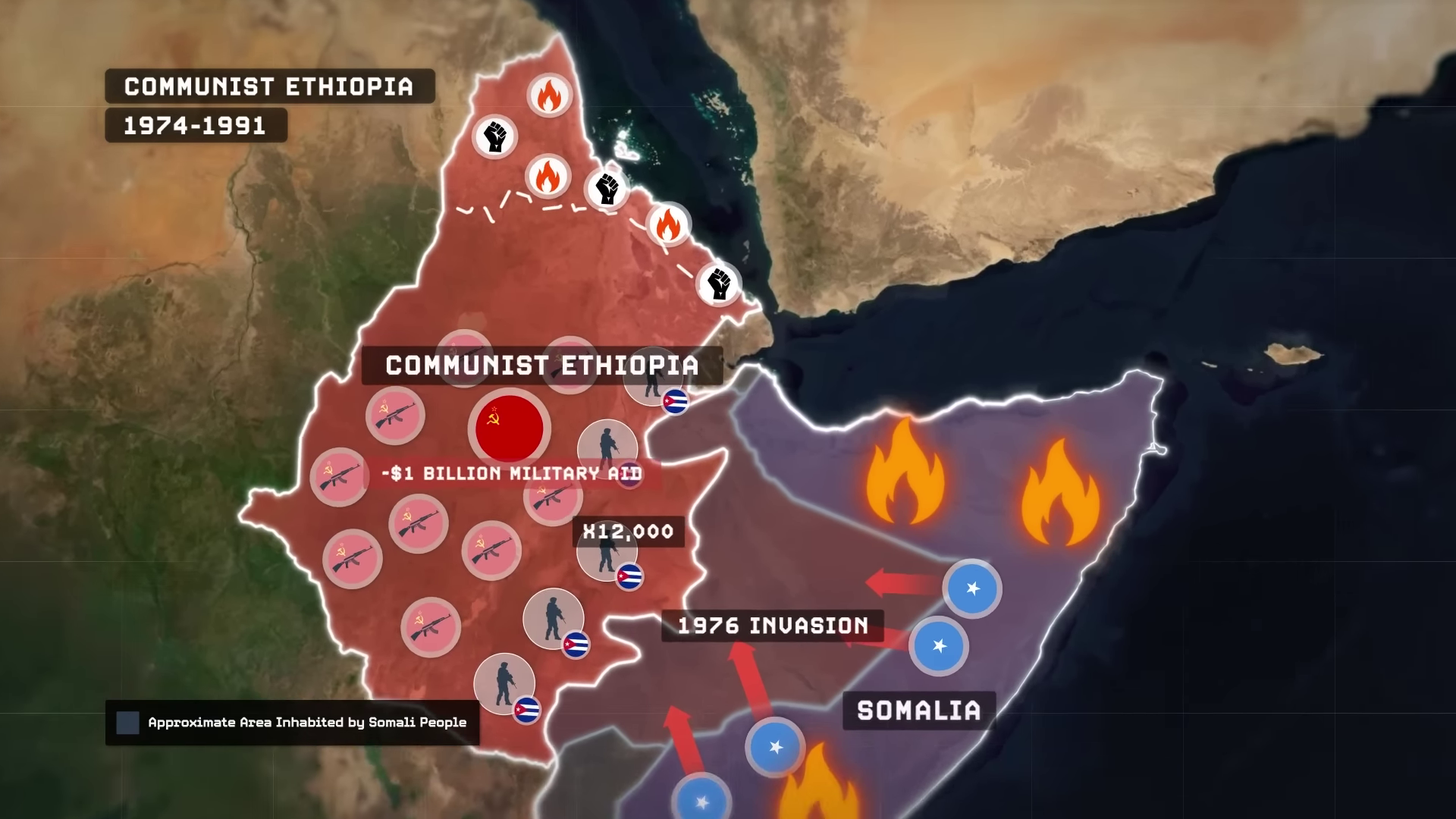

Decades later, in 2002, he was overthrown, and a major named Mengistu Haile Mariam was appointed as essentially the country’s new dictator, seeking to radically transform the former feudal monarchy of Ethiopia into a communist Marxist-Leninist state called the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The new communist Ethiopia inherited the continuing war for independence going on in Eritrea that they similarly attempted to crush with force. While Somalia sensed an opportunity in the revolutionary chaos and invaded Ethiopia in 1976 in an attempt to conquer the ethnically Somali majority area of the Ogaden. But with Ethiopia now ruled by communists and the Americans out of the country, the Soviets decided to abandon their prior support for Somalia and switch sides over to Ethiopia. The Soviets then organized a massive airlift of military equipment to Ethiopia worth around 1 billion dollars, accompanied by Soviet military advisors and about 12,000 soldiers who came over from Fidel Castro’s Cuba, who together decisively crushed the Somali invasion. That defeat was so significant that it led to a revolt in the Somali army afterwards, which was the spark that ignited the Somali Civil War that is still ongoing today, a war that has long made Somalia the 21st-century poster child of the failed state.

The Ethiopian Famine and Political Changes in the 1990s | 0:18:40-0:22:00

But while Ethiopia’s territorial integrity was maintained, including its control over the ongoing insurgency in Eritrea, the communist regime’s gross mismanagement of the Ethiopian agricultural economy, combined with a drought, led to an apocalyptic famine between 1983 and 1985 that potentially killed as many as 1.2 million people within the country, with deaths most heavily represented where active rebellions against his regime were ongoing in Eritrea and in Tigray. They were largely denied assistance, representing one of the worst famines of the entire 20th century.

Unrest and anger at the communist regime’s response to the famine within Ethiopia grew, and anti-government rebellions like the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in the Tigray region, who allied with the Eritrean insurgents, began steadily gaining the upper hand. In 1990, with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc actively collapsing, Moscow decided to cut off their continued economic assistance to Ethiopia, and the thousands of allied Cuban troops all went home, cutting off Mengistu’s 17-year-long communist regime from its primary supporter.

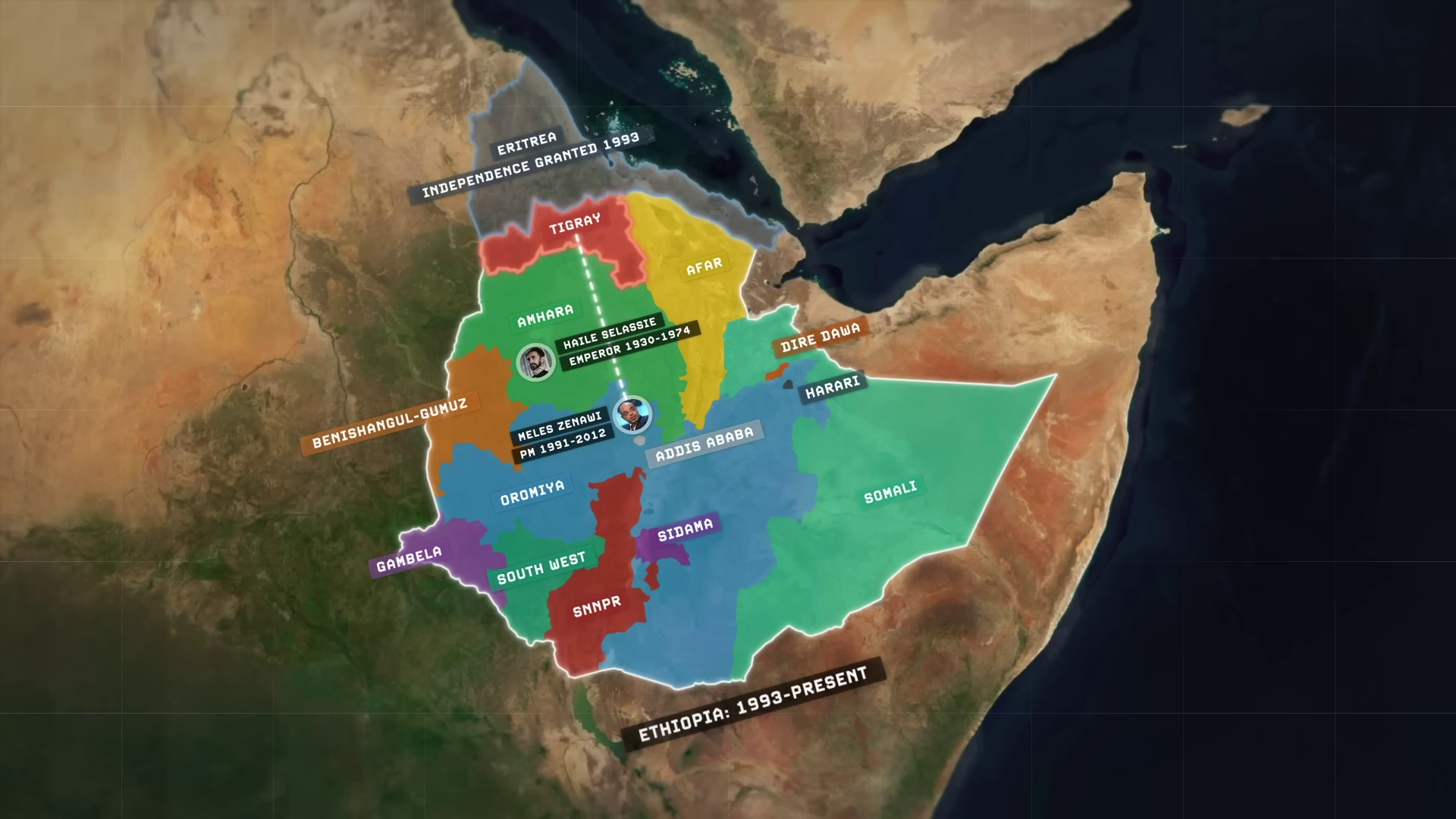

Afterwards, the various anti-government forces operating across the country began rapidly gaining even more ground. The Eritrean insurgents secured complete control over the entirety of Eritrea and pushed the Ethiopian army out by May of 1991. Anti-government Tigrayan forces were nearing the capital of Addis Ababa when Mengistu fled the capital for Zimbabwe. He was granted political asylum and continues to reside there to this day at the age of 86, despite an Ethiopian court subsequently finding him guilty of genocide in absentia, carrying a death sentence. Ethiopia has repeatedly requested his extradition from Zimbabwe, which has continually rejected for decades, ever since the new Ethiopia that emerged after the collapse of communism in 1991 became the federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

A new constitution was drafted that transformed the entire country into an ethnically based federation with powers devolved to 12 new ethnolinguistically defined regional states and two chartered cities. These 12 new regions were semi-autonomous states created within the country for all of Ethiopia’s largest ethnic groups: the Oromo, the Amhara, the Tigray, the Somali, the Afar, and so on. But the very first leader of the new country, who governed until his death in 2012, was an ethnic Tigrayan named Meles Zenawi from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which caused significant angst within the ethnic Amhara community, who had been accustomed to running Ethiopia in all of its various forms for the past several centuries.

Initially, Eritrea was the 13th region of this new Ethiopia created after 1991, since the Tigrayans and the Eritreans had fought together as allies to overthrow the communist regime. After the Eritreans secured control over their entire territory, a referendum on Eritrean independence from Ethiopia was granted in April of 1993, which was overwhelmingly approved by Eritrean voters. This led to Eritrea being formally granted its independence by Addis Ababa the following month in May, marking the first time that Eritrea had been truly independent in well over a century.

Immediately upon independence in 1993, a man named Isaias Afwerki rose to the position of Eritrea’s new presidency. He has continued to remain Eritrea’s president ever since, up until the current day, more than 30 years later. Isaias has run what is often regarded as one of the most extreme totalitarian regimes in all of contemporary history in Eritrea. No elections have ever been held in the more than 30 years since Isaias came to power. There has never been a constitution, a published government budget, or even a legislature. Literally, all political power and authority within Eritrea has been solely concentrated in the person of Isaias Afwerki since 1993.

The Frozen Conflict Between Ethiopia and Eritrea: A Timeline of Events

The political climate in Eritrea, under Isaias's regime, is characterized by extreme totalitarianism, including mandatory military conscription with no feasible means of discharge, and stark limits on media and press freedom. The severe punishments for defying or attempting to escape military service have led to prolonged conscription terms, often lasting decades. Critics liken this indefinite armed service to a 21st-century form of slavery.

Troubled relations between Isaias's regime and the government in Ethiopia stem from the tenuous trust established immediately post-independence in 1993. Tensions escalated in 1998 over disputed territories, leading to a violent, two-year war, culminating in Ethiopian control of the disputed lands.

Following the violent disputes over land, the United Nations facilitated the Algiers Agreement in December 2000, leading to a proposed ceasefire. Creation of a boundary commission and arbitration court was agreed upon, to resolve the territorial disputes. In 2002, the commission awarded the contested territories to Eritrea but Ethiopia refused to relinquish control, leading to a protracted and tense frozen conflict lasting 16 years.

Relations between the two countries saw a promising shift in 2018 with the election of Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed. Soon after taking office, Abiy declared acceptance of the 2002 Border Commission ruling, and Ethiopian forces withdrew from the disputed territories, marking a significant move towards reconciliation and regional stability.

Efforts to Make Peace with Eritrea | 0:28:20-0:32:40

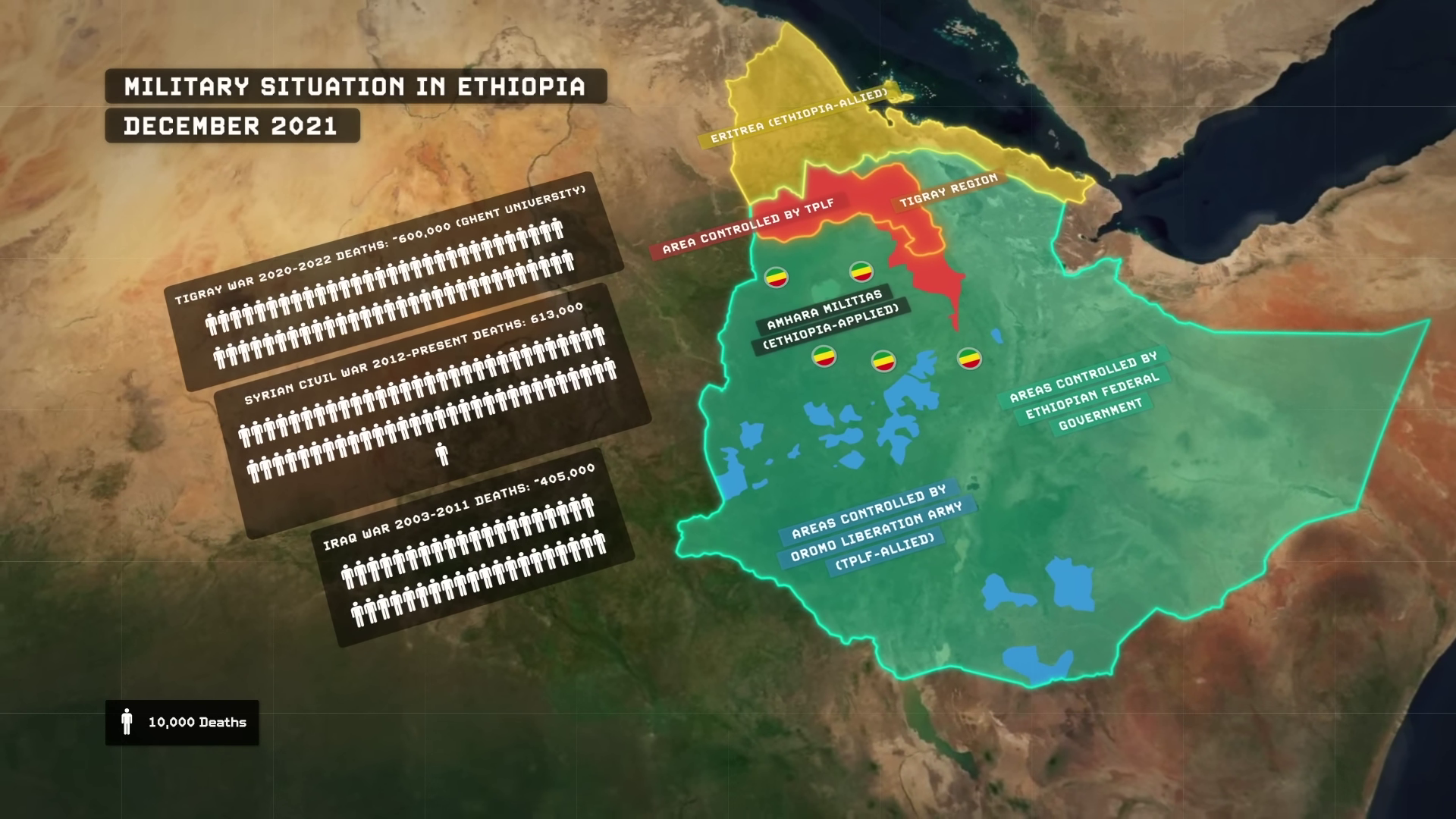

During the 1990s, attempts were made to negotiate peace with Eritrea, culminating in the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Abiy Ahmed in 2019. Nonetheless, the border dispute resolution did not result in a ceasefire, and internal conflicts among various ethnic groups arose in Ethiopia. The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) criticized the peace agreement, sparking a full-scale war in the Tigray region in 2020. This conflict involved the Ethiopian federal government, Eritrea, Amhara militias, and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), resulting in significant loss of life over two years.

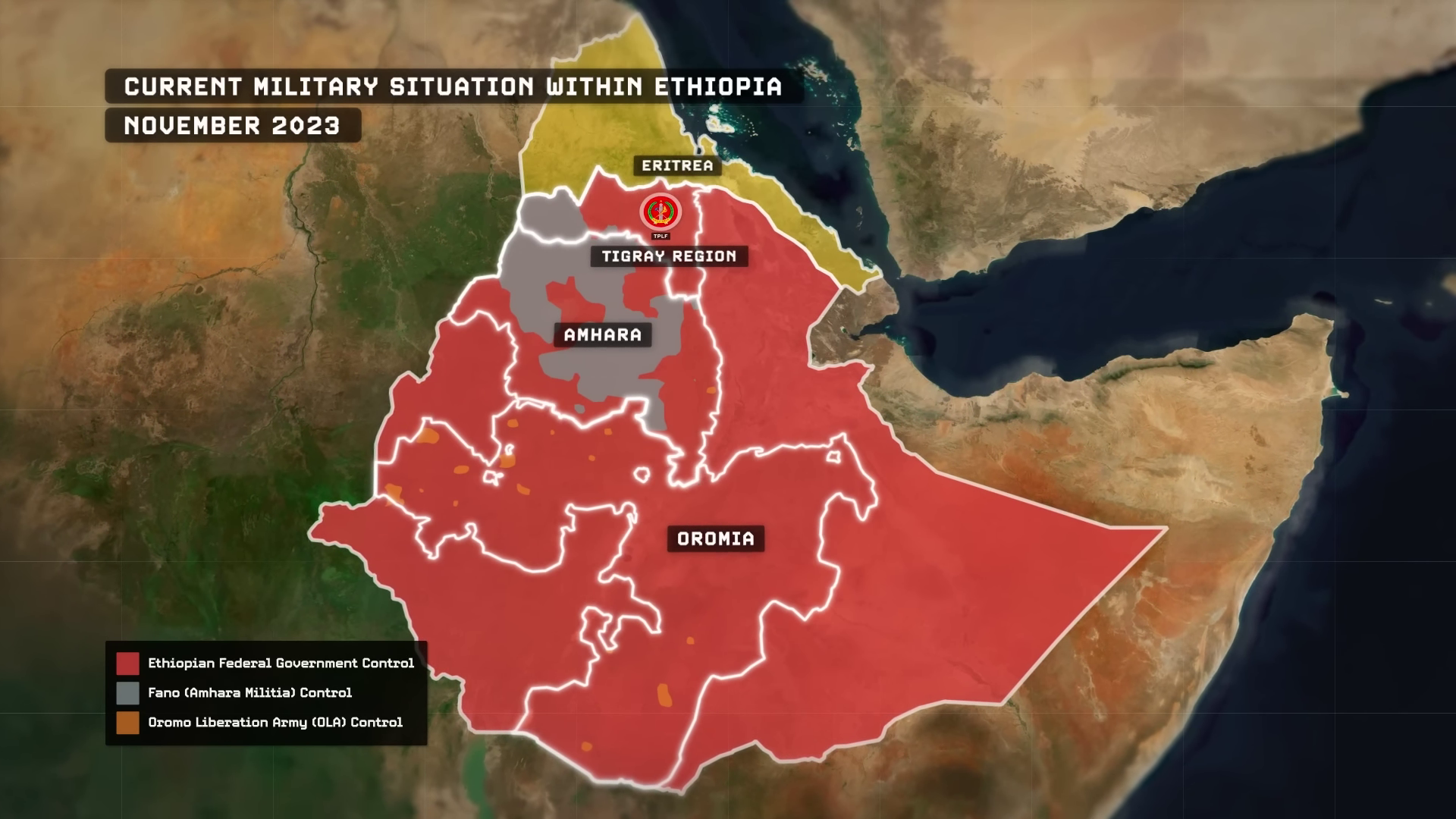

The Tigray War, one of the deadliest conflicts of the 21st century, resulted in significant human and economic loss, with an estimated $20 billion worth of economic damage inflicted on Ethiopia. Despite the signing of a peace treaty in South Africa in November 2022 between the Ethiopian federal government and the TPLF, internal conflicts within Ethiopia remain. Control remains divided across the Oromo region due to an ongoing insurgency by the Oromo Liberation Army.

Fano promotes Amhara nationalism intertwined with Ethiopian nationalism, with the primary objective to reinstate Amhara leadership in the country. Conversely, Abiy Ahmed's federal government stands for Ethiopian unity and national identity above regional ethno-linguistic and religious differences. As a result, his government opposes regional separatism, causing disputes with the TPLF in the Tigray region, the OLA in the Oromia region, and now FANO in the Amhara region. The discord between the federal government and FANO advanced in April 2023 when the government tried to disarm Fano, a command they refused to obey.

Ethiopia's Struggle for Port Access and Naval Ambitions | 0:33:40-0:39:20

Ethiopia's struggle for port access has caused more conflicts within the nation, specifically with the Fano armed insurgency. By the middle of 2023, Ethiopia's federal authorities reclaimed control over most of the Tigray region, but conflicts with the OLA in the Oromia region and Fano in the Amhara persisted. Deeper international problems arose when Eritrea refused to grant Ethiopia port access in Assab or Massawa, intensifying their relations further.

In October 2023, Ethiopia proposed exchanging shares of their Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam megaproject for shares in coastal countries' ports, such as Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia. This offer was rejected by all mentioned countries, insisting their ports' sovereignty is non-negotiable. Despite this setback, there is hope for Ethiopia's Navy to return to the Red Sea, as it once did in the past.

The Ethiopian Navy, currently headquartered at Lake Tana, anticipates its position at the Red Sea, similar to its position from the 1950s to the 1990s. With global attention being diverted to the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, Ethiopia may contemplate attacking Eritrea. This possible assault on Eritrea aims at driving out the Eritrean occupation from the Tigray region and apparently to overthrow the totalitarian regime.

However, the real unspoken objective is likely to reclaim lands or completely reincorporate Eritrea back into Ethiopia. If this eventuates, uncertainties will rise on all sides since Eritrea, despite being outnumbered in population, has been more unified than the internally unstable Ethiopia. While their enforced army might dislike their dictator, it is anticipated that the threat of an Ethiopian imposition could rally them together.

Potential Consequences of Launching a War Against Eritrea for Ethiopia | 0:39:20-

Starting a war against Eritrea could be both advantageous and disastrous for Ethiopia. The nation is still recovering from the Tigray War (2020-2022), which inflicted economic damages worth over 20 billion dollars and resulted in likely hundreds of thousands of casualties. Ethiopia is currently negotiating with the IMF for loans to assist in recovery efforts. However, another war could endanger these discussions and lead to further economic hardships. Additionally, any attempt to annex Eritrea would potentially be met with international criticism and sanctions. Nonetheless, the need to secure its long-term objectives, including acquiring a coastline, could motivate Ethiopia to proceed with the war.

Ethiopian forces are reportedly amassing near the Eritrean border, increasing the likelihood of a conflict. Should an invasion occur, Ethiopia is expected to focus its primary attacks around the port of Assab, a strategic location previously used by Ethiopia until Eritrea's independence in 1991. The significance of Assab has grown since 2015, when Eritrea permitted the United Arab Emirates to build a naval and airbase there. The Emiratis used the base to conduct swift assaults on Houthis in Yemen, which lead to a modernization of facilities in Assab.

After the United Arab Emirates' withdrawal from Assab in 2019, discussions have been held between Eritrea and Russia regarding the potential usage of the port by the Russian Navy. Ethiopia might aim to seize control of the port before such an agreement is reached, to secure a modernized port on the Red Sea for the Ethiopian Navy.

In terms of logistics, defending Assab would be a challenge to Eritrea, mainly due to its distant location from the country's capital, Asmara. There's only a single road connecting Assab to Asmara, which is less than 5 miles away from the Ethiopian border at its closest point. Other potential war objectives for Ethiopia may include integrating the whole of Eritrea and establishing control over a long coastline along the Red Sea, as the nation did in 1952 under Emperor Haile Selassie. Some historical arguments within Ethiopia claim the nation's borders naturally extend to the coastline, harking back to the ancient Axumite kingdom and Selassie's 20th-century empire.