Why France is Actually Preparing for War With Russia - RealLifeLore

RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Proxy War Between French and Russians in Niger | 0:00:00-0:00:20

- Countries in Africa’s Sahel region experiencing successful coups and violent conflicts | 0:00:20-0:07:00

- Challenges in French Colonial Expansion in Africa | 0:07:00-0:16:00

- France’s Reliance on Niger’s Uranium for Nuclear Energy | 0:16:00-0:19:00

- France’s Influence in Former African Colonies | 0:19:00-0:24:40

- Counter-arguments against the CFA franc | 0:24:40-0:30:00

- Impact of Climate Change | 0:30:00-0:31:40

- France’s Military Intervention in Mali | 0:31:40-0:36:40

- The Russian Mercenary Wagner Group in Africa | 0:36:40-0:46:00

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U

Proxy War Between French and Russians in Niger | 0:00:00-0:00:20

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=0 There is a massive proxy war between the French and the Russians across the African continent that has the potential to impact the rest of the world. In July 2023, the world's attention was briefly on the emerging proxy war between Moscow and Paris in Niger, a landlocked country in West Africa.

Countries in Africa’s Sahel region experiencing successful coups and violent conflicts | 0:00:20-0:07:00

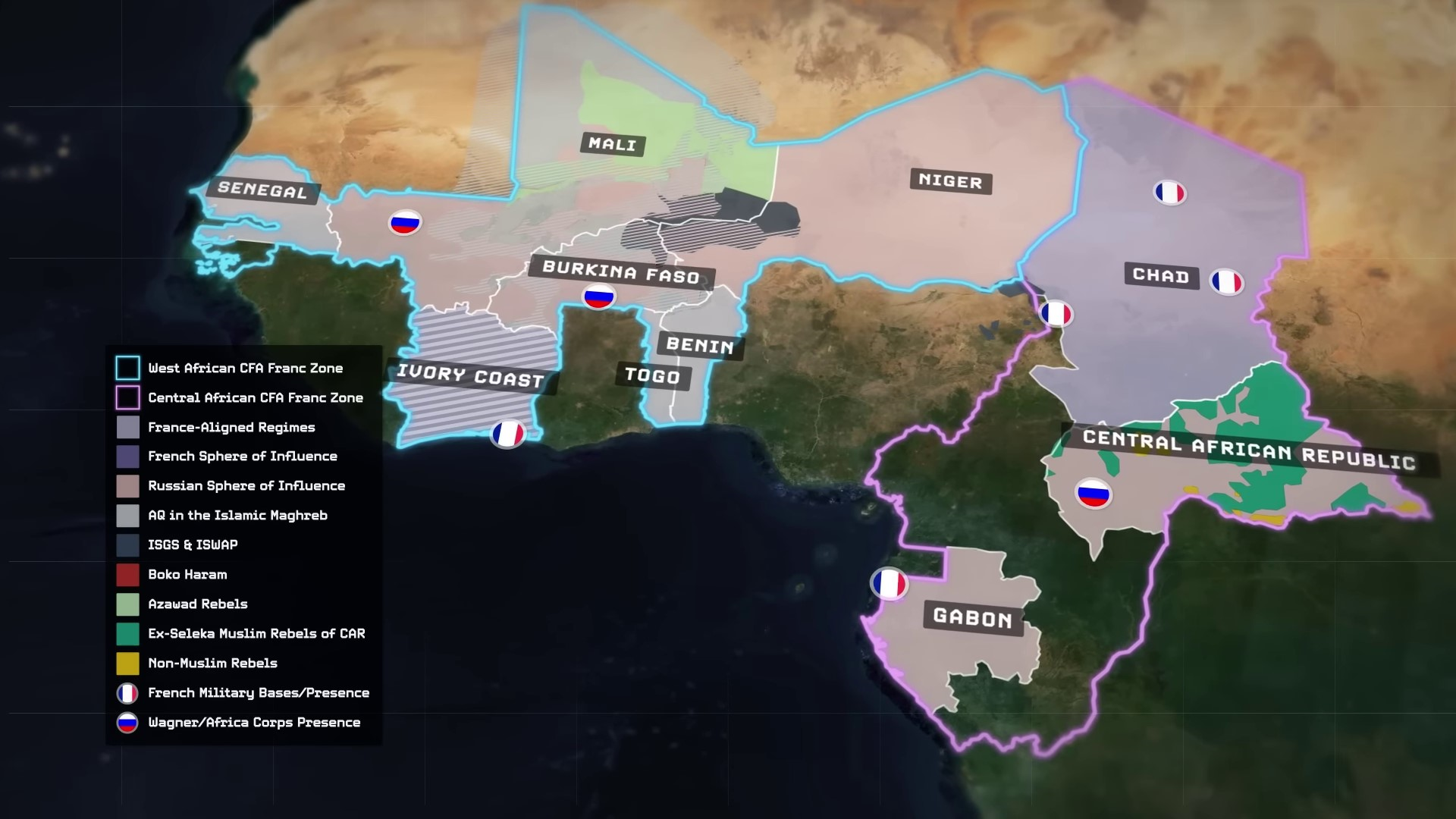

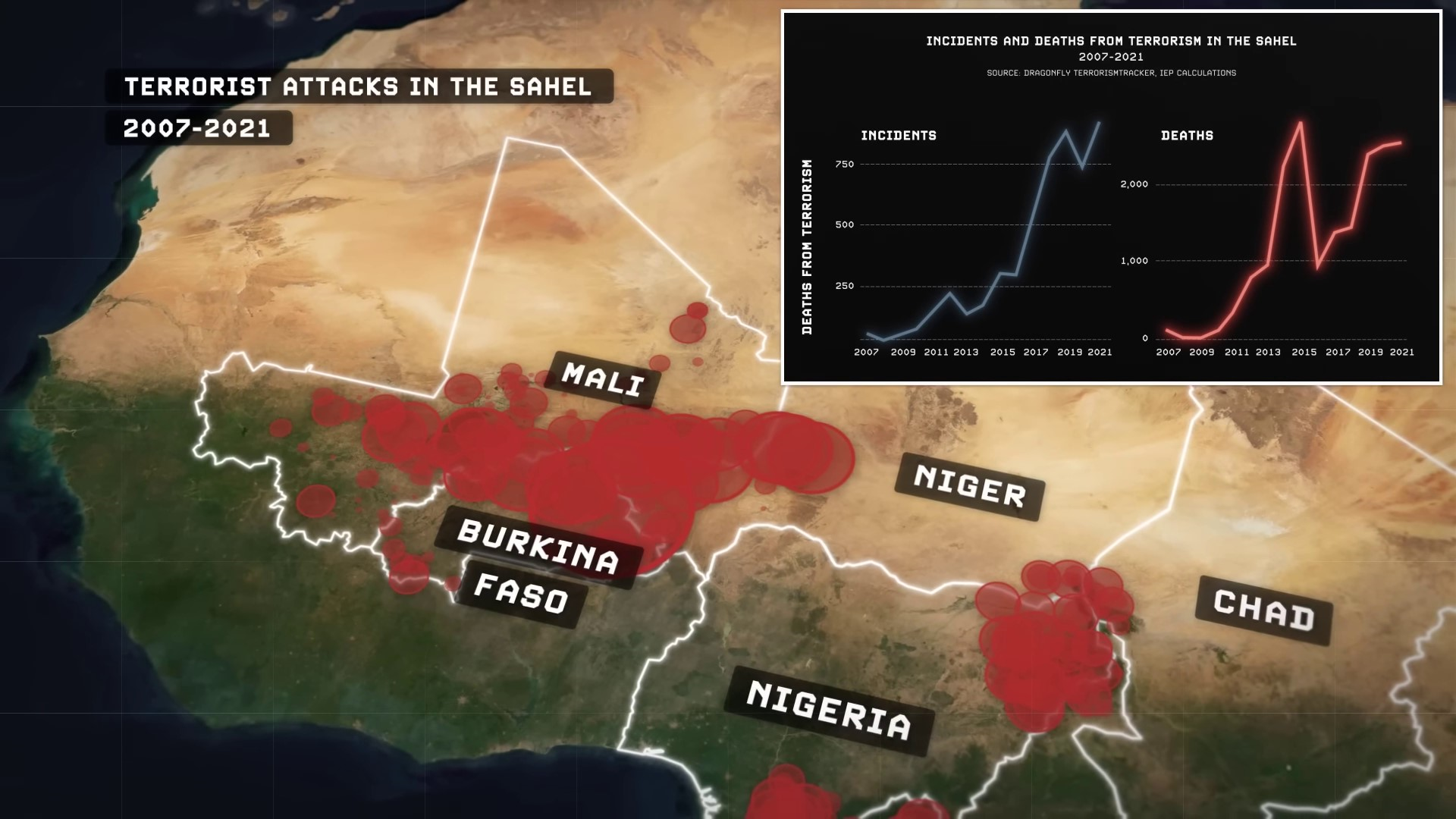

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=20 In recent years, several countries in Africa’s Sahel region, including Niger, have experienced successful coups that lead their governments being overthrown. This trend has created a ‘coup belt’ across Africa, with countries like Mali, Chad, Sudan, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger being affected. The region is also facing violent conflicts, such as the civil war in Sudan and the presence of radical Islamist factions in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Despite these challenges, the international attention on these issues remains limited.

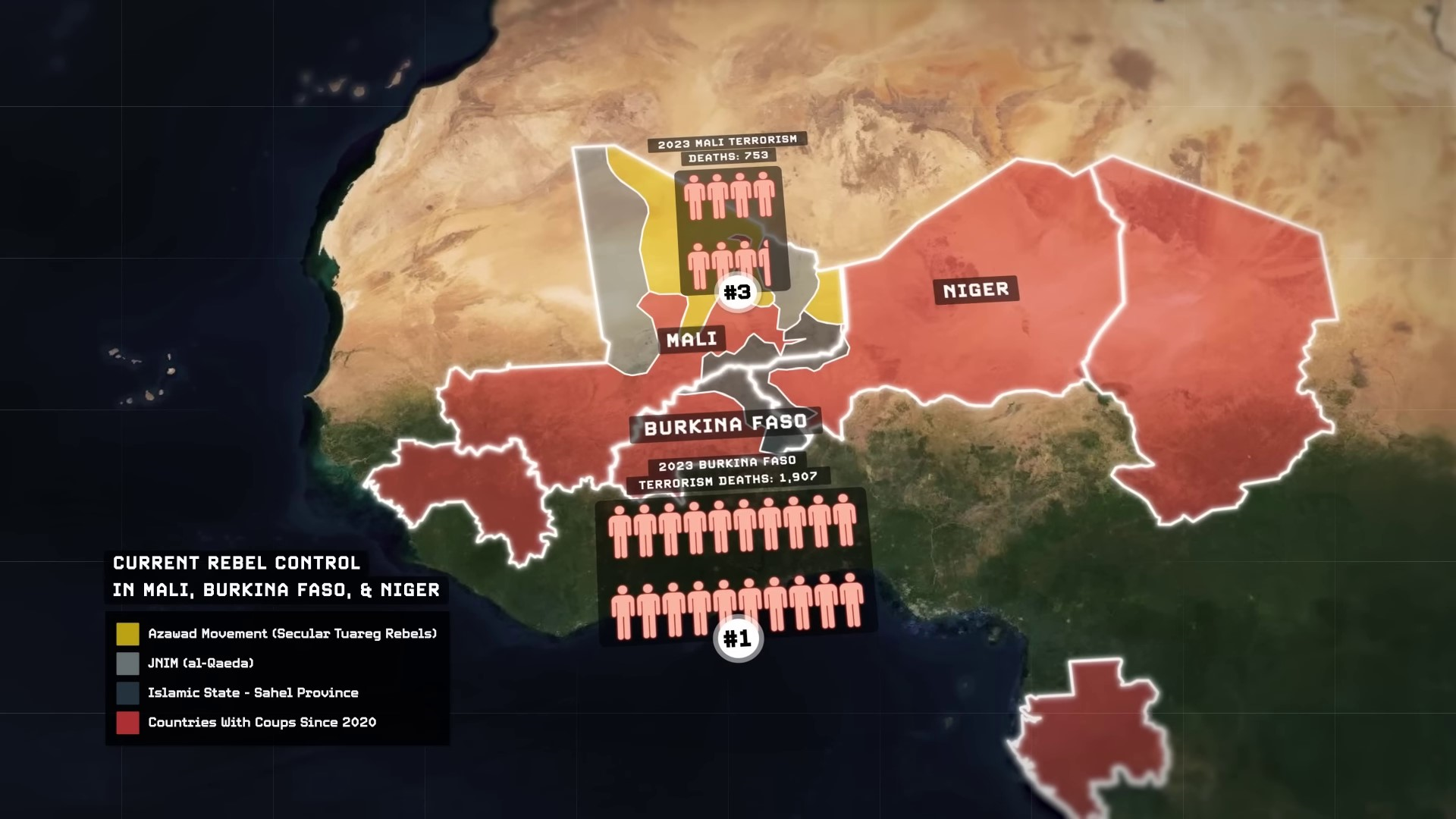

After the collapse of ISIS in Iraq and Syria, and after the expulsion of Al-Qaeda from Afghanistan, both groups have reformed themselves and re-centered their primary territorial bases of operations away from the Middle East, towards the Sahel region.

Amidst the chronic instability in the ‘coup belt’, tens of thousands of people have lost their lives and millions more have been displaced in the process. In 2023, for the very first time since the global terrorism index began compiling records 13 years ago, a country other than Afghanistan or Iraq climbed into the number one spot for deadly terror attacks attacks, and it wasn’t Israel even after the widely publicized scale of Hamas’s October 7th attack. It was Burkina Faso, who suffered nearly 2,000 deaths from terrorism in 2023 alone. This represented nearly a quarter of all terrorism-related deaths worldwide, and represented a surge of terrorism-related violence in the the country up 68% compared to 2022.

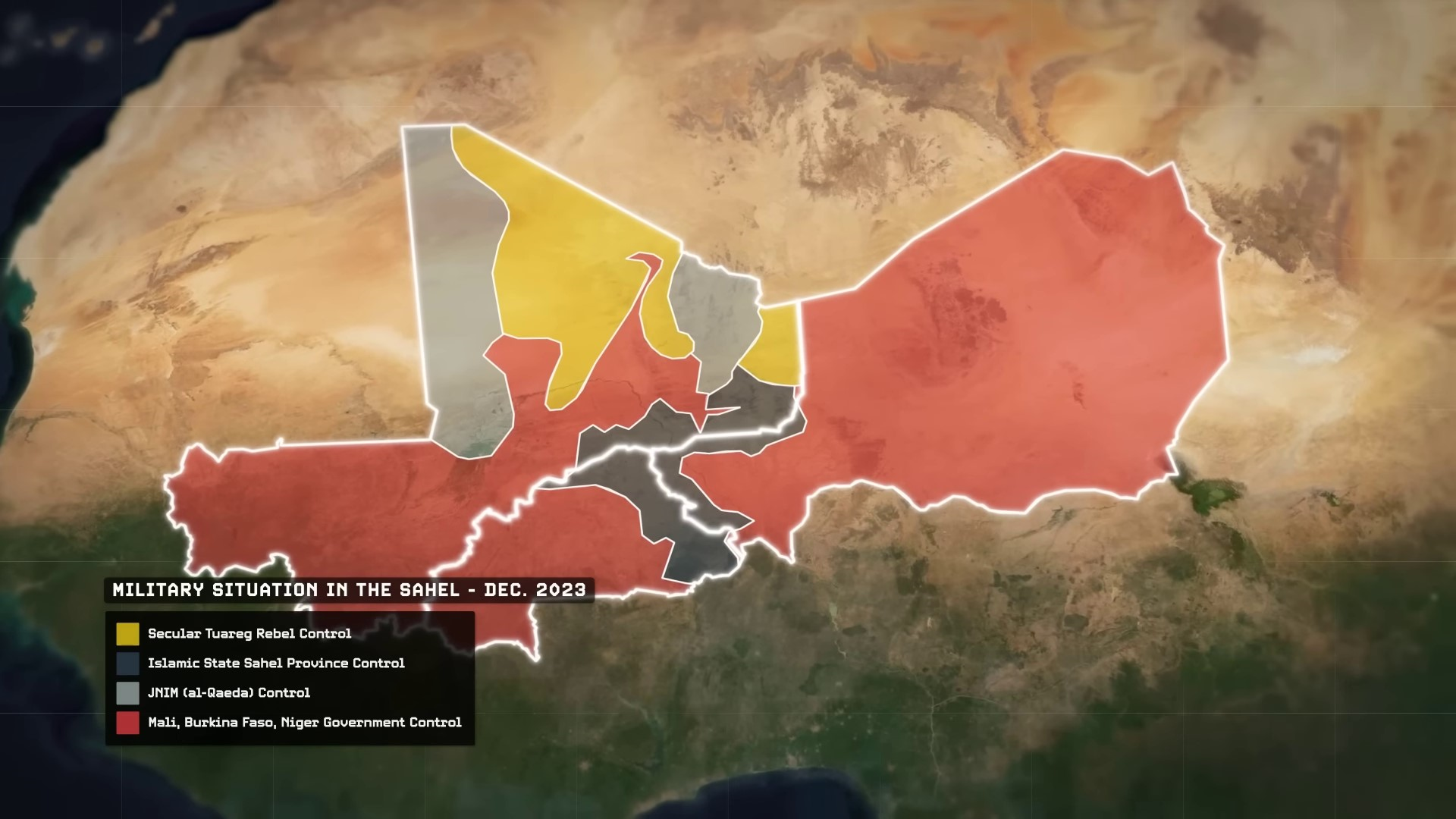

And neighboring Mali wasn’t far behind it in third place overall, suffering more deadly terrorism in 2023 than either Pakistan or Syria. This has made the tri-point border region between Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger the new epicenter of global terrorism in the 21st century, as much of it is fallen under the direct control of either ISIS or Al-Qaeda. There is a genuine fear that many of these countries may be on the verge of imminent state collapse. All of these unstable and fragile countries in Africa’s ‘coup belt’ are formerly, and arguably still current economic, if not political, colonies of France. In nearly every one of these countries were home to thousands of French troops, who were ostensibly there fighting against the likes of ISIS and Al Qaeda. but who were also there to defend major French economic interests.

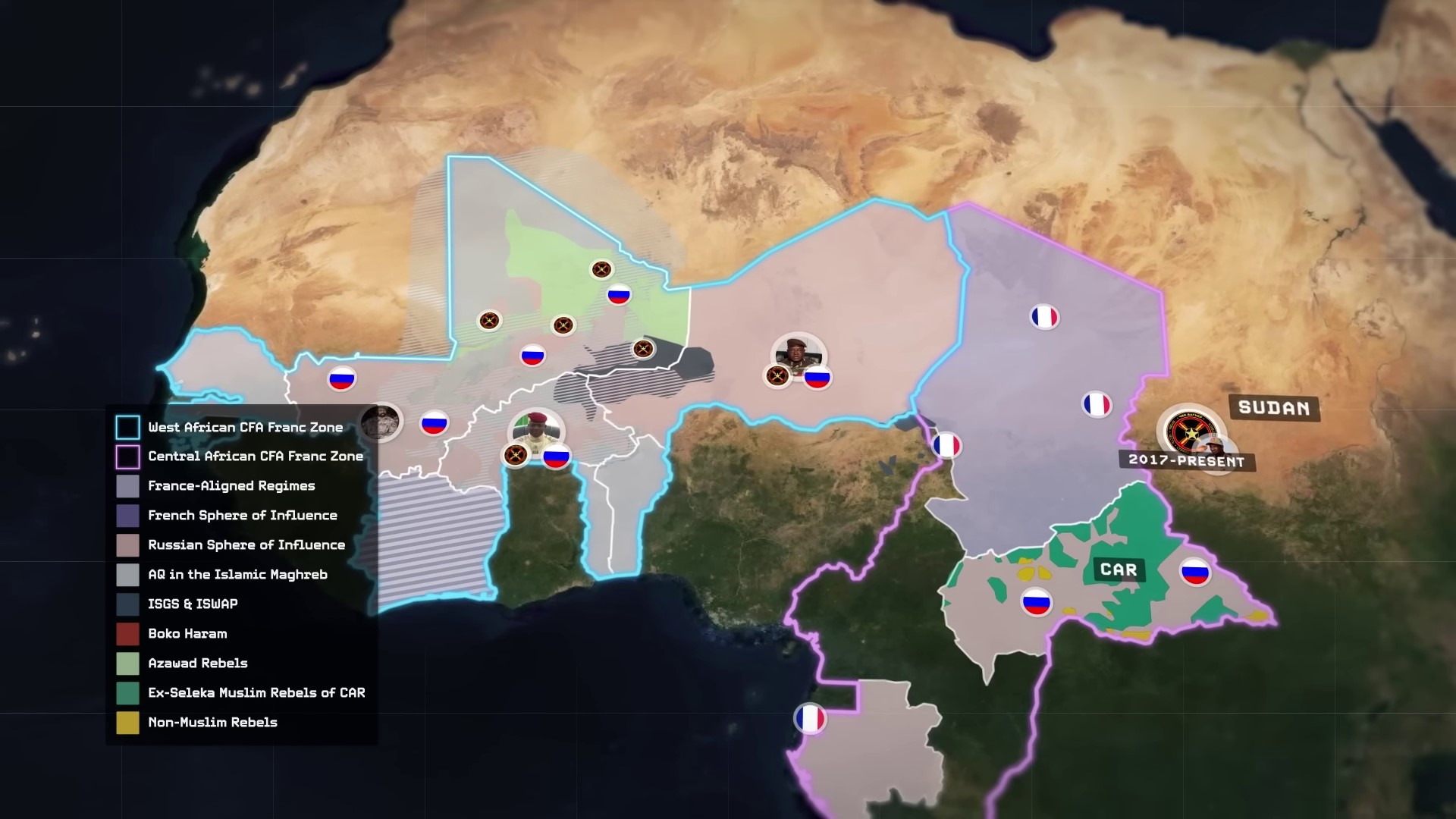

This was before the coup leaders took power and expelled them from the country. Since the coups overthrew governments in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, French troops and even the French ambassadors have all been collectively expelled. As a wave of anti-French sentiment sweeps across the continent, and in nearly every instance, the expulsion of French troops and French ambassadors have been met with a welcoming of hundreds to even thousands of new Russian troops from the mercenary Wagner group. This new group was fully rebranded as the Russian Africa Corps to fight against the ongoing insurgencies. As the spaces on the board in West Africa begin rapidly shifting like 'falling dominoes' away from France’s sphere of influence and towards Russia’s, a complicated proxy war overlaps the struggles between West African nations, tribes, and ethnicities themselves.

That is directly challenging France’s long, profitable, largely invisible neo-colonial domination over former directly ruled colonies in Africa, which has continued for generations. This has become a threat to France’s foundation and prosperity. The instability in the Sahel region of Africa in the 2020s is emphasized as crucial to the future of both Europe and Africa.

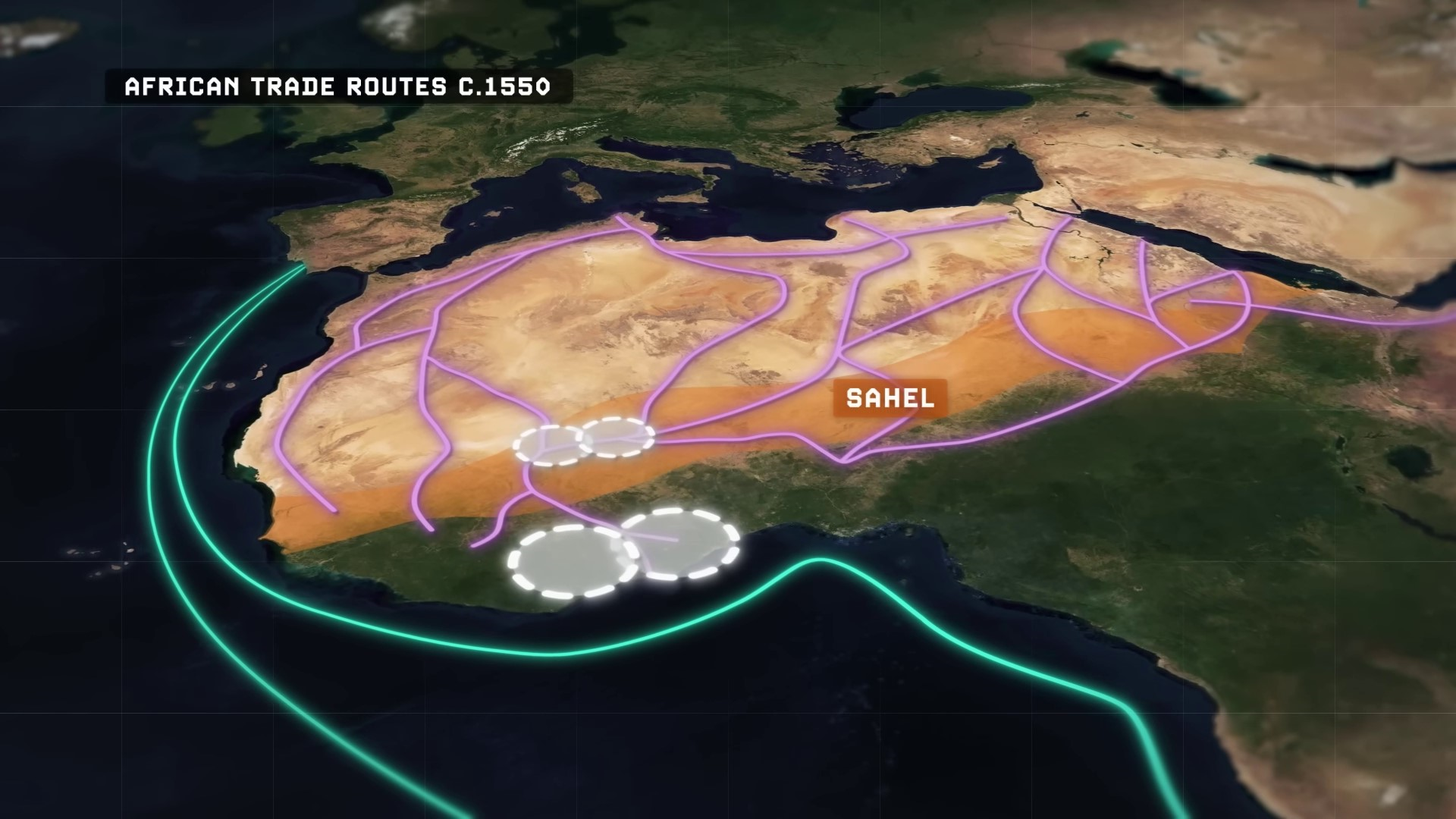

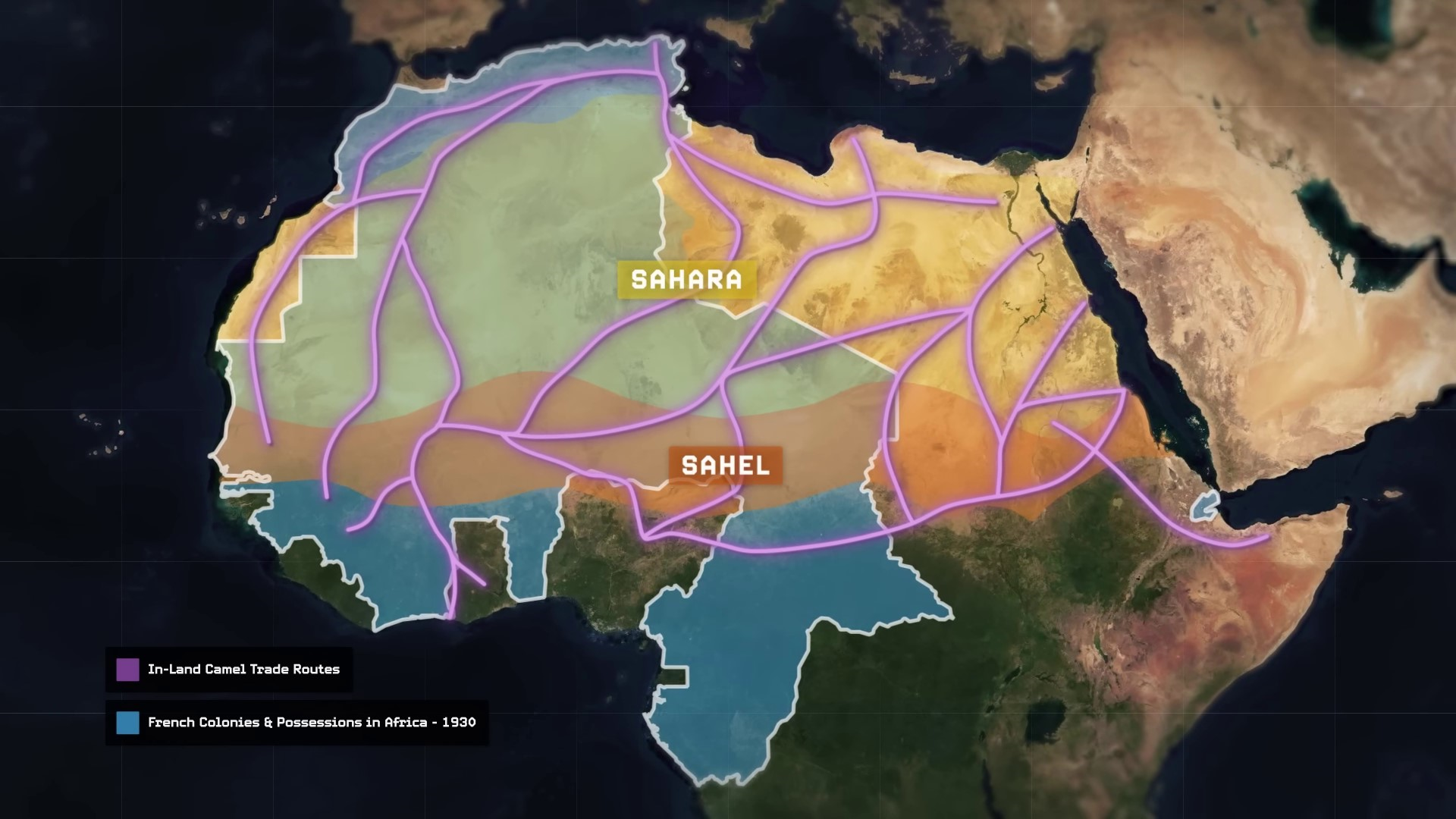

The Sahel region in Africa has a unique history shaped by French colonialism and neo-colonialism, intersecting with geography, climate change, and Russia’s geopolitical objectives. It was once a wealthy trading hub connecting the Sahara desert to sub-Saharan Africa, with cities like Timbuktu flourishing. However, European maritime trade routes in the 15th century shifted the trade dynamics. French colonialism in Africa left long-lasting effects, impacting the region’s development and politics till today. The economic fortunes of the Sahel began declining over the following centuries as new maritime ports emerged in places like Ghana and Ivory Coast. This decline was evident by the time of the Berlin Conference in the late 19th century.

Challenges in French Colonial Expansion in Africa | 0:07:00-0:16:00

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=420 The French colonial empire in Africa expanded rapidly across the continent without considering important factors such as overland camel trading routes, ecological differences between regions, boundaries of ethnicities, and distinctions between nomadic and settled groups.

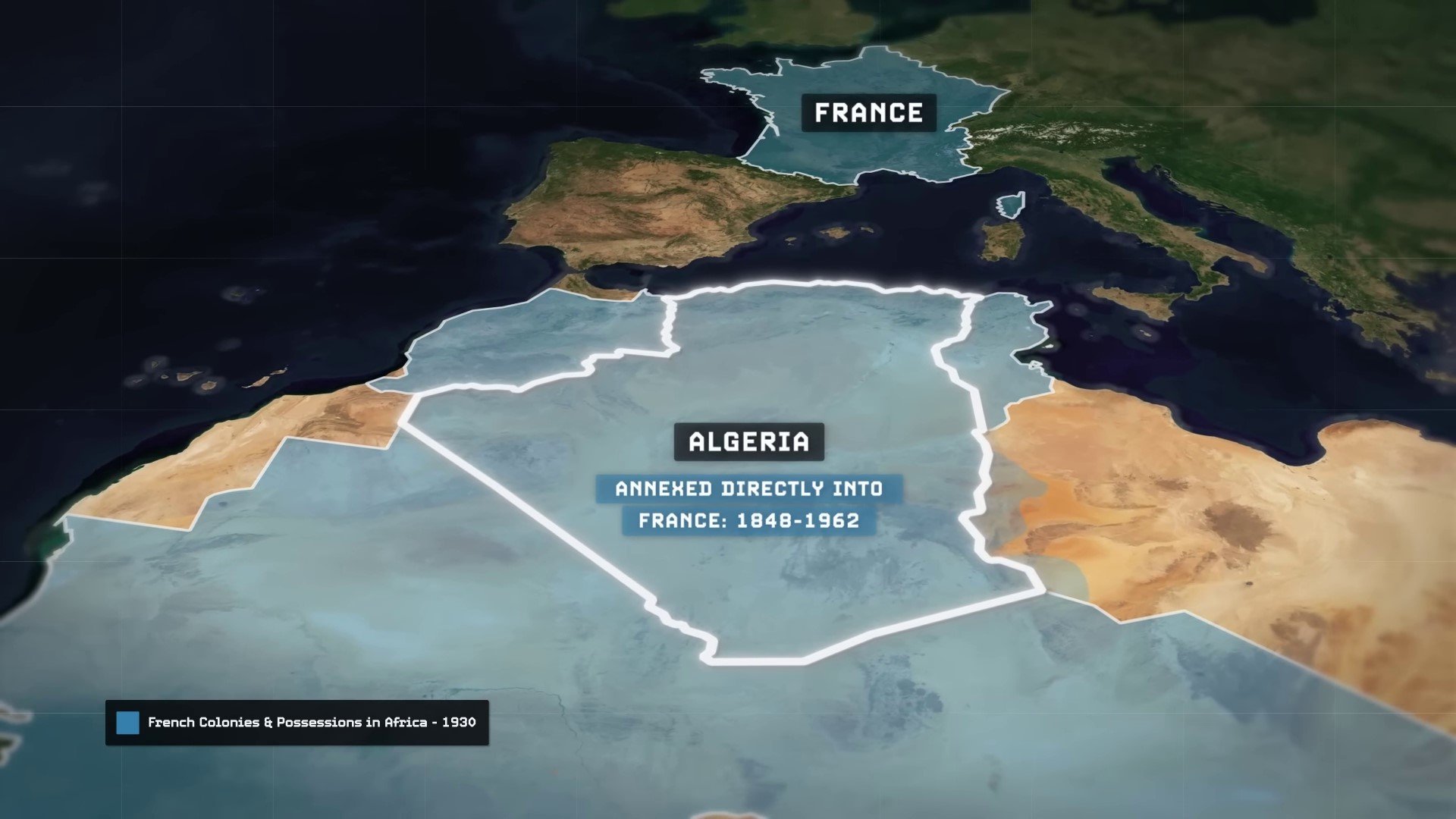

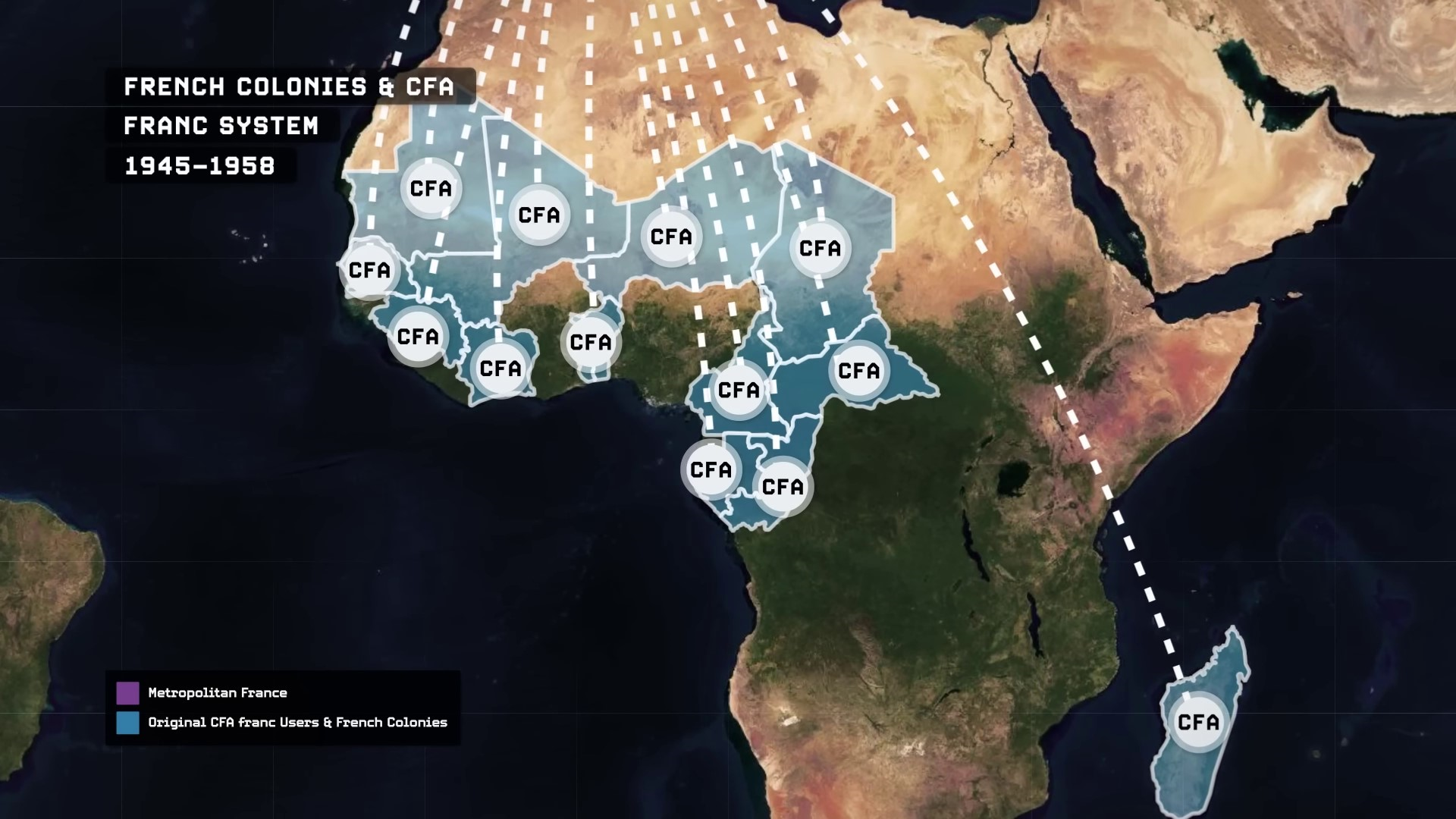

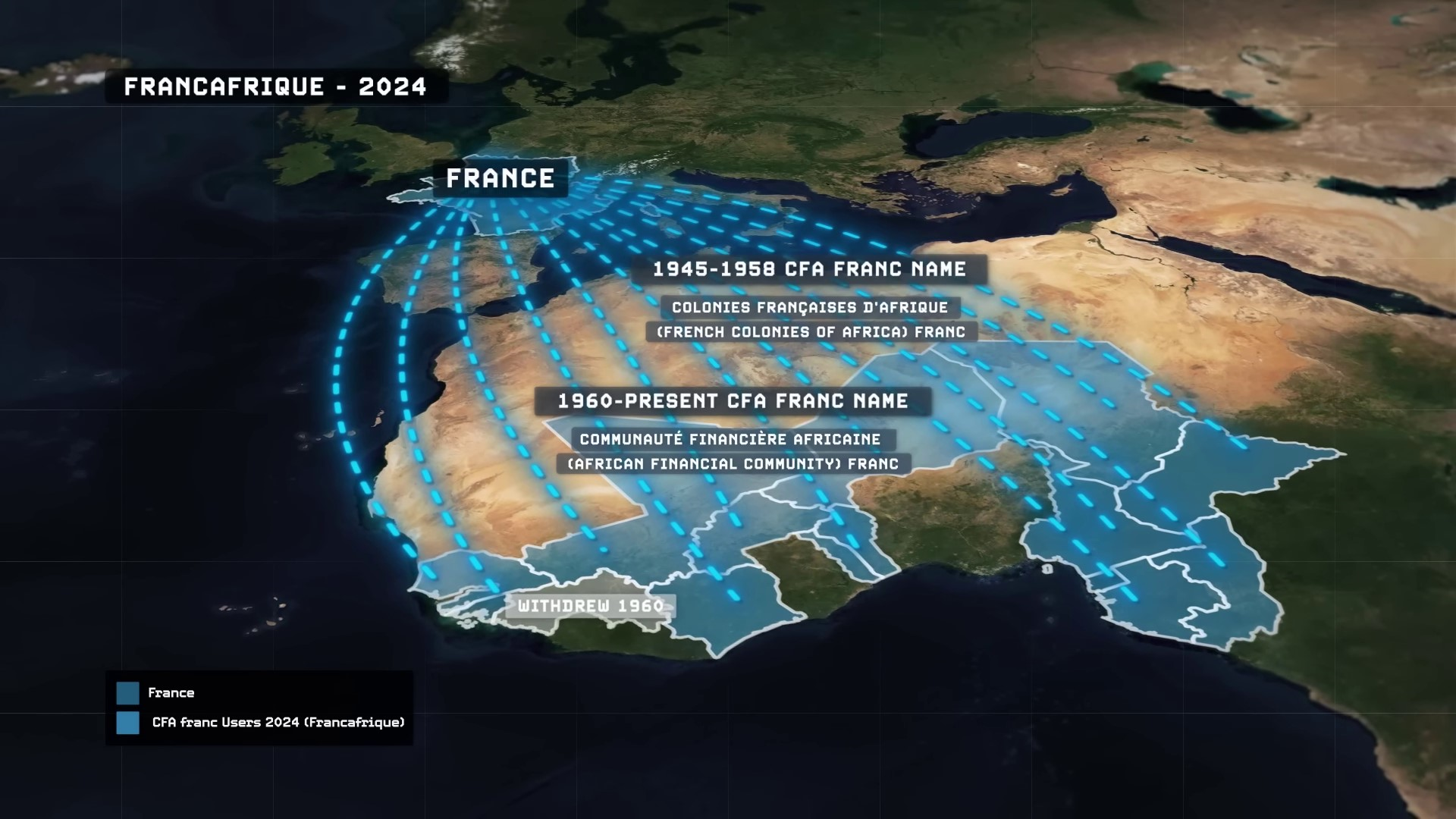

The French colonial authorities in Algeria annexed the region into the French nation in 1848, leading to a significant influx of French settlers. France established the CFA franc in 1945 for its African colonies, maintaining a fixed exchange rate with the French franc to benefit French interests. This system allowed France to exploit African resources and control trade, leading to growing calls for independence in Africa.

France responded to calls for independence in its colonies with overwhelming violence, particularly in Algeria where a revolution broke out in 1954. The brutal seven-year war for independence saw the French army committing massacres and atrocities in an effort to crush the Algerian independence movement. Paris considered Algeria a core integral territory of France, leading to ruthless tactics in suppressing the uprising. It’s estimated that around one million Algerians were killed. Almost 8,000 Algerian villages were destroyed, and more than 2 million Algerians were rounded up and placed into French-run concentration camps. The French also treated the sparsely populated Algerian Sahara as their testing ground for nuclear weapons during the war as well, testing and detonating a total of 17 nukes in the country between 1960 and 1966, that exposed thousands of locals to radiation.

Over time, the Algerian war’s brutality and high costs gradually turned French public opinion against it, as did international support for the war from France’s allies like the United States, which eventually forced France to concede and grant Algeria its independence in 1962. This led to a mass exodus of more than 900,000 of the French settlers who lived in Algeria back to metropolitan France, who were terrified of suffering Algerian reprisals.

And as all of this brutality and horror was very publicly going on for the whole world to see in Algeria, France began attempting to hang on to the rest of their African colonies through more covert, less expensive, less bloody, and less internationally damaging methods. After having pressed the CFA franc currency on them in 1945, the French essentially hijacked and co-opted genuine independence movements in the rest of their West African colonies by courting, influencing, and placing their hand-picked local elites into positions of power, as essentially puppets before offering them their theoretical independence.

Each of these colonies were then offered so-called cooperation agreements by Paris that would define their future relationship with France going forward post-independence. These agreements differed from colony to colony. These leaders sometimes granted French companies continued privileged access to their natural resources. They sometimes enabled the French to continue maintaining military bases in their countries. But they always advised the colonies to continue remaining within the CFA franc financial system.

The colonies that accepted these cooperation agreements post-1958, and remained within the CFA franc system, have always been presented by the French as a peaceful negotiation. However, some flatly rejected France’s offers after independence in 1958, including the prospect of remaining within the CFA franc system. Guinea’s then-leader Sekou Touré, in a defiant speech in front of France’s then-president Charles de Gaulle, declared his preference for impoverished freedom over wealthy slavery. France responded by making an example of him, removing any luxuries, including medicine and light bulbs, whilst eliminating all foreign aid to Guinea.

Subsequently, Guinea turned towards the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc for financial experts to develop its own independent currency in 1959. This was seen by the French as a direct threat to their CFA franc system. In retaliation, they flooded Guinea with counterfeited currency to stimulate hyperinflation and crash their economy and even went so far as to arm Guinean rebels.

When responding to other threats in Africa against their new colonial system, the French resorted to similarly violent methods. Felix Roland Mouny, a Cameroonian anti-colonialist leader, was assassinated by the French Secret Service in Switzerland in 1960. His death, caused by a poisoning with radioactive thallium, paralleled the current methods used by Vladimir Putin to eliminate his enemies in Europe.

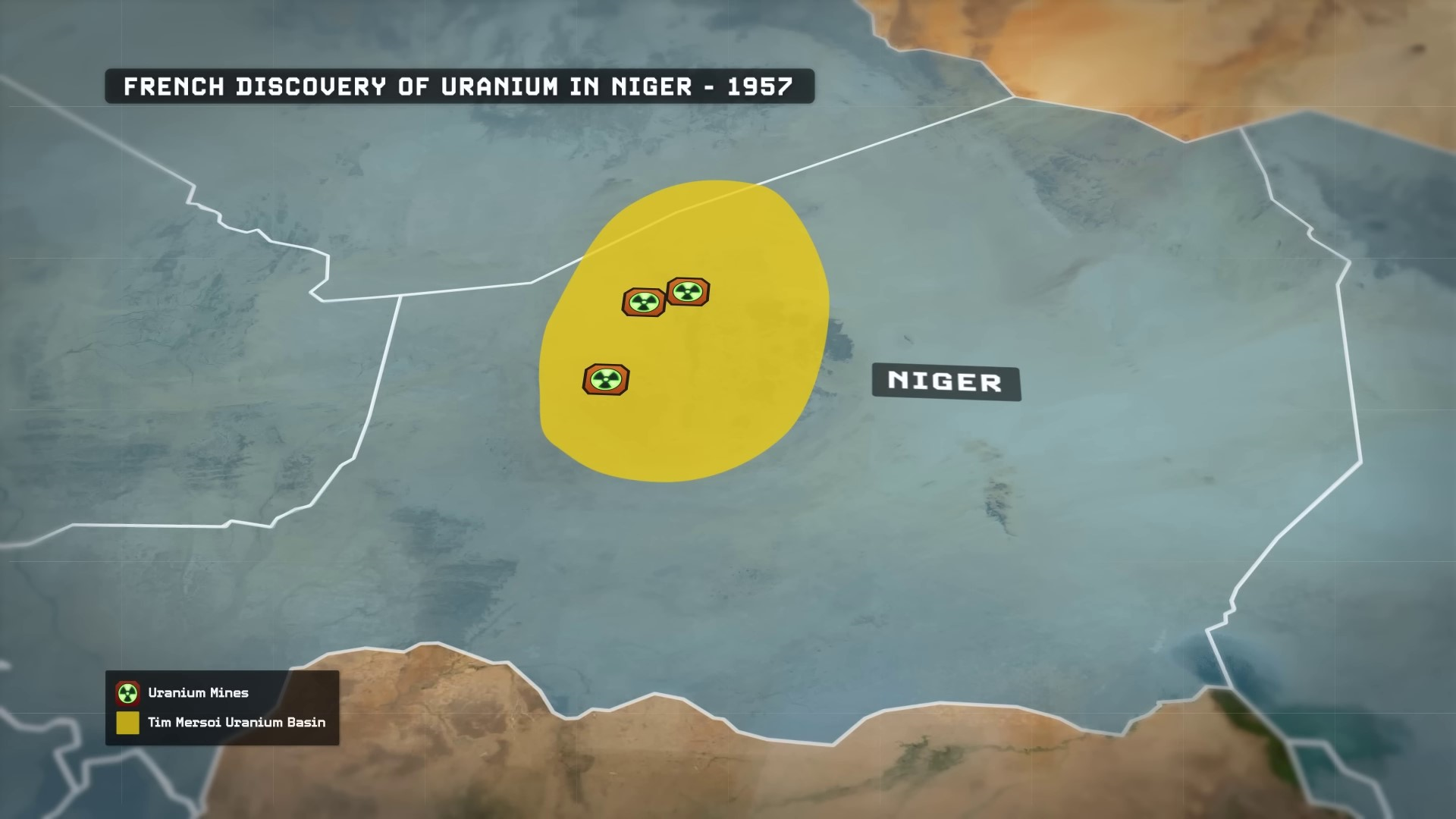

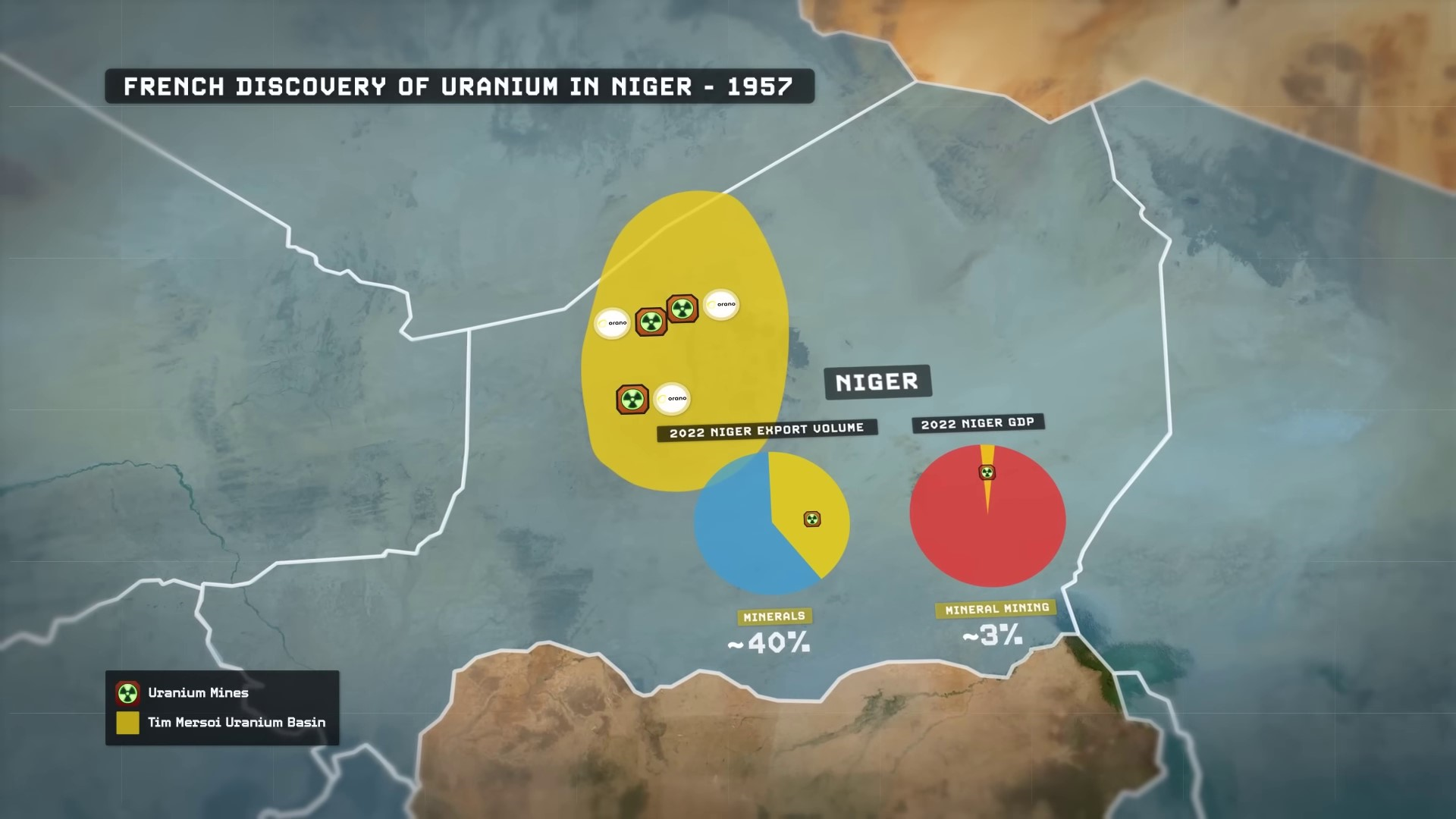

In 1957, just before the decolonization, French geologists discovered large uranium reserves in a remote part of northern Niger. It turned out that Niger had the seventh-largest known reserves of uranium in the world, and the highest quality uranium ore ever discovered on the African continent. The French continued to seek access to this uranium in Niger to develop their own independent nuclear weapons arsenal, in a bid to achieve strategic autonomy from both the United States and the Soviet Union.

France’s Reliance on Niger’s Uranium for Nuclear Energy | 0:16:00-0:19:00

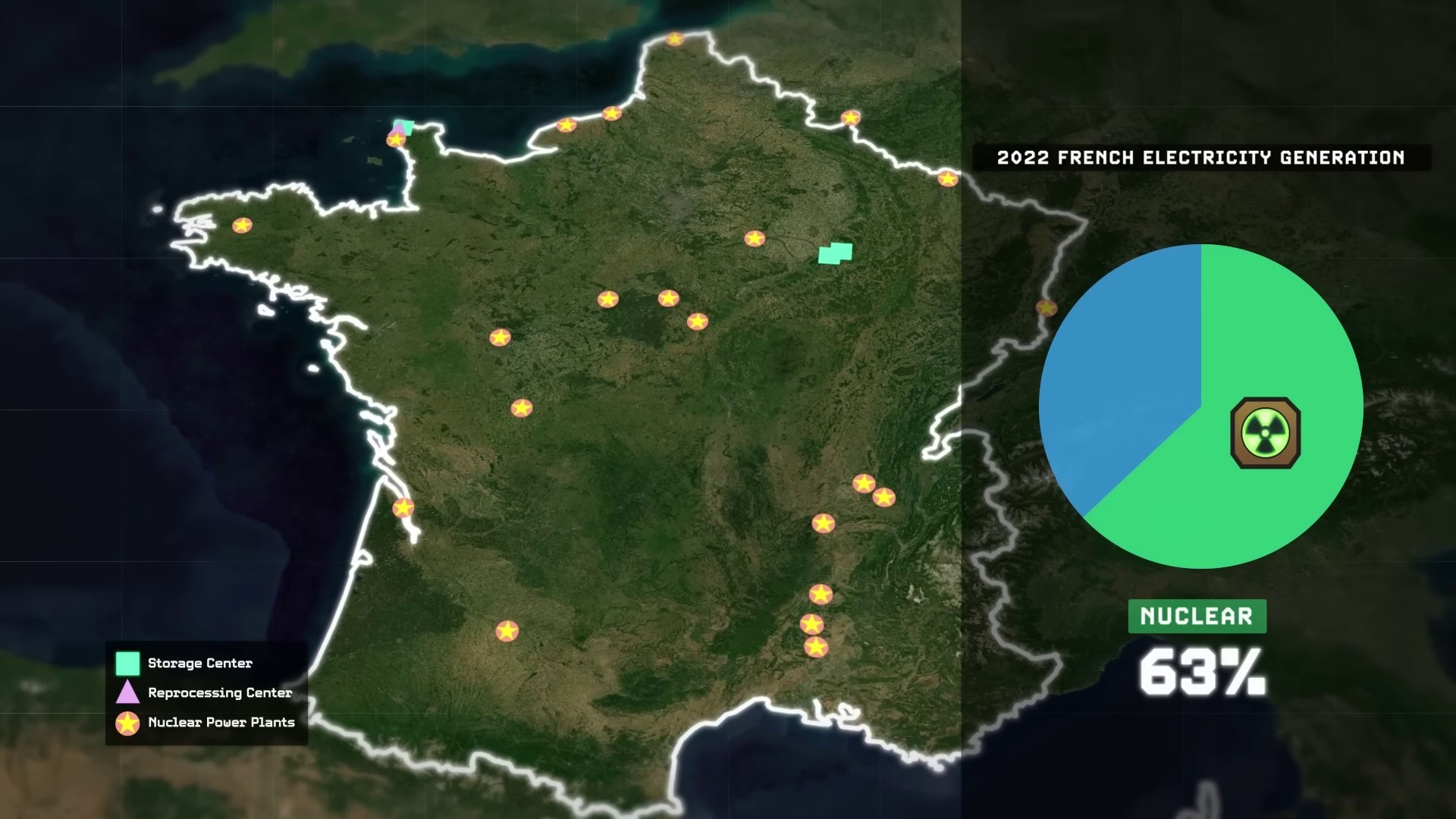

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=960 France has heavily relied on Niger's uranium to power its nuclear energy industry, with the first French-owned uranium mines in Niger opening in 1971. Today, France is home to 56 nuclear reactors and 18 nuclear power plants, generating 63% of its electricity. France requires around 8,000 tons of raw uranium ore per year to fuel its nuclear reactors, as it lacks uranium within its own borders.

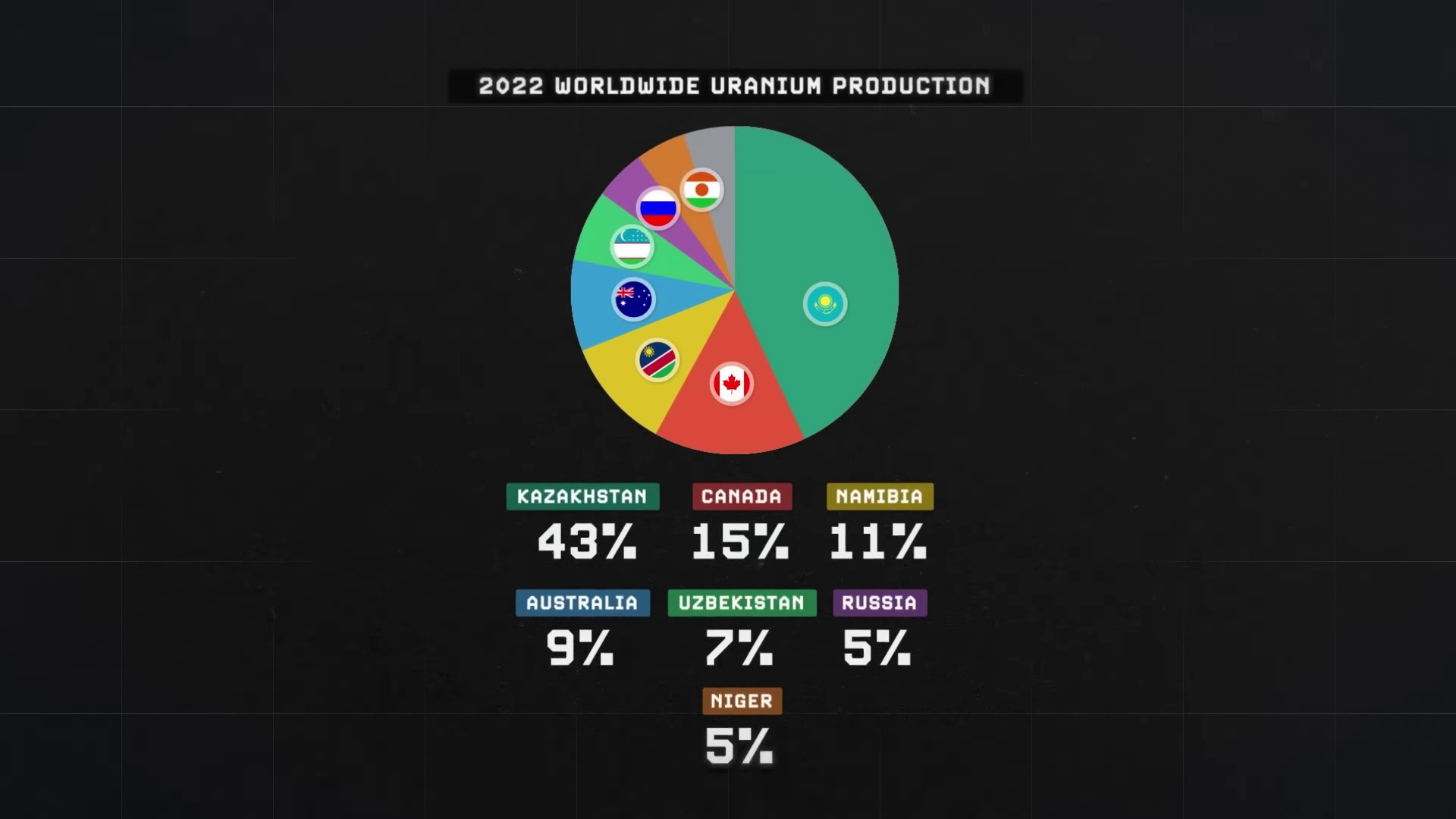

France is the largest producer of uranium in the world, accounting for 43% of global production in 2022. In contrast, Niger is a minor player, producing only about 5% of the world’s supply.

The CFA franc financial system has been in place in France’s former colonies for decades after their independence. Niger's exports have always been expensive and uncompetitive, unless they are exported to France. The latter had been able to use its undervalued currency, pegged to the overvalued CFA franc, to purchase them below market value. Niger had no other choice but to sign grossly unfair deals with French multinational companies that exploited their uranium resources and transported them back to France.

Orano, the multinational uranium mining company headquartered in Paris and 90% owned by the French government, currently operates three uranium mines in Niger. However, only one of these mines remains operational as of 2024. Despite Niger being a minor uranium producer globally, accounting for 5% of worldwide uranium production, it continues to be a major source of French uranium imports.

Kazakhstan, the world's largest uranium producer, is France's primary uranium supplier, providing roughly 37% of France's uranium imports in 2022. Yet, Niger remains France's second largest source, having provided 20% of French imports that same year. In 2022, 80% of all the uranium produced in Niger by French-owned multinational companies such as Orano was exported to France, which powered roughly 12.5% of France's total electricity. In other words, about 8 million French citizens rely on the importation of uranium from Niger to power their homes.

Thus, Niger's uranium has remained a core strategic interest for France up to the present day. For Niger, despite mineral mining like uranium production, uranium accounting for 40% of the country's export volume, it only contributes about 3% of the country's GDP. This is due to the fact that very few of the profits from uranium mining have remained within Niger. Additionally, Niger's uranium was not the only raw material in France's colonial empire that Paris sought to maintain access to after granting independence.

France’s Influence in Former African Colonies | 0:19:00-0:24:40

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=1140 Significant oil deposits were discovered in Gabon when it was still directly ruled as a colony by France in 1931. After Gabon's theoretical independence in 1960, the French wanted to maintain access to the oil, just as they did with Niger's uranium. In the mid-1960s, a Gabonese man named Omar Bongo was essentially interviewed by French President Charles de Gaulle for the position of Gabon's president and was appointed shortly after.

An ardent Francophile, Bongo ruled the country for decades, until 2009 when his son, Ali Bongo, succeeded him and continued the pro-French dictatorship in Gabon. He held power until he was overthrown in August 2023. During the Bongo's reign, they allowed the forerunner of today's giant French oil company Total to dominate Gabon's oil production in exchange for an annual bribe, sometimes amounting to 50 million euros per year.

In 1988, The New York Times reported that France covered about one-third of the Bongo government’s budget in Gabon. Most of it flooded into Omar Bongo’s personal accounts, enriching the Bongo family and enabling the French to maintain their privileged status. In 1999, a US Senate investigation into Citibank revealed that Omar Bongo had about $130 million stashed in personal bank accounts, making him one of the world's wealthiest heads of state.

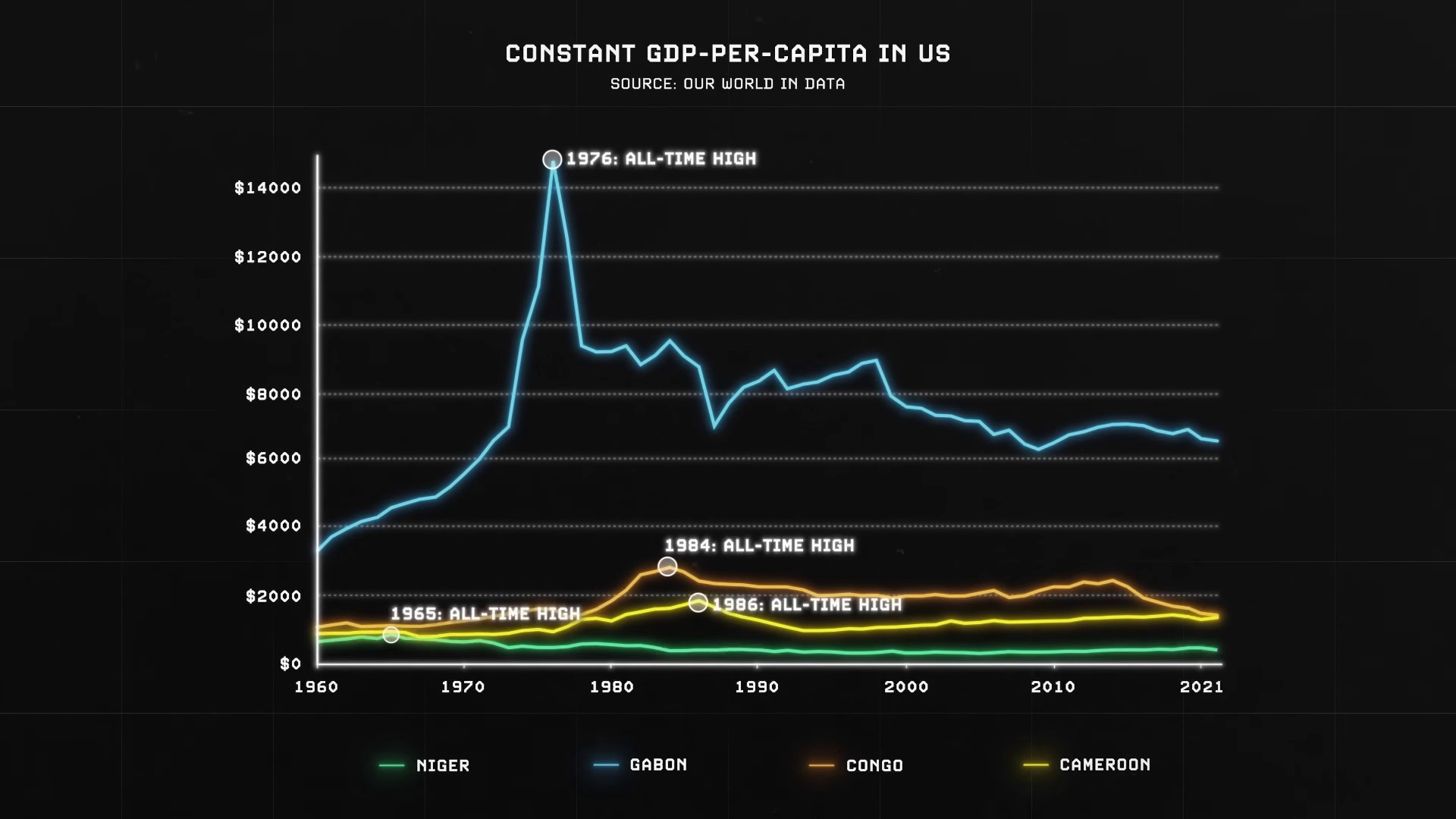

Despite Gabon’s oil-dominated GDP per capita being among the highest in Africa during his four-decade-long rule, his government only paved about five kilometres of roads annually. Gabon still had one of the world’s highest infant mortality rates at the time of his death in 2009, with one-third of the population living in poverty. Much of the nation's wealth was hoarded by the Bongo family and France.

Ever since West African colonies gained their theoretical independence in 1960, the CFA franc system has largely remained in place, benefitting France. The French launched at least 122 separate military interventions into Africa between 1960 and the mid-1990s to protect its ongoing economic interests. This included deploying hundreds of marines and tanks to Gabon in 1990 to suppress riots against their puppet, Omar Bongo's rule.

The CFA franc system saw some transformations over the decades with some countries, like Guinea, Madagascar, and Mauritania, withdrawing from it and others, such as Equatorial Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, who were never original French colonies, joining it. It is still used by 14 countries in West and Central Africa today, most of whom were once directly ruled as colonies from Paris.

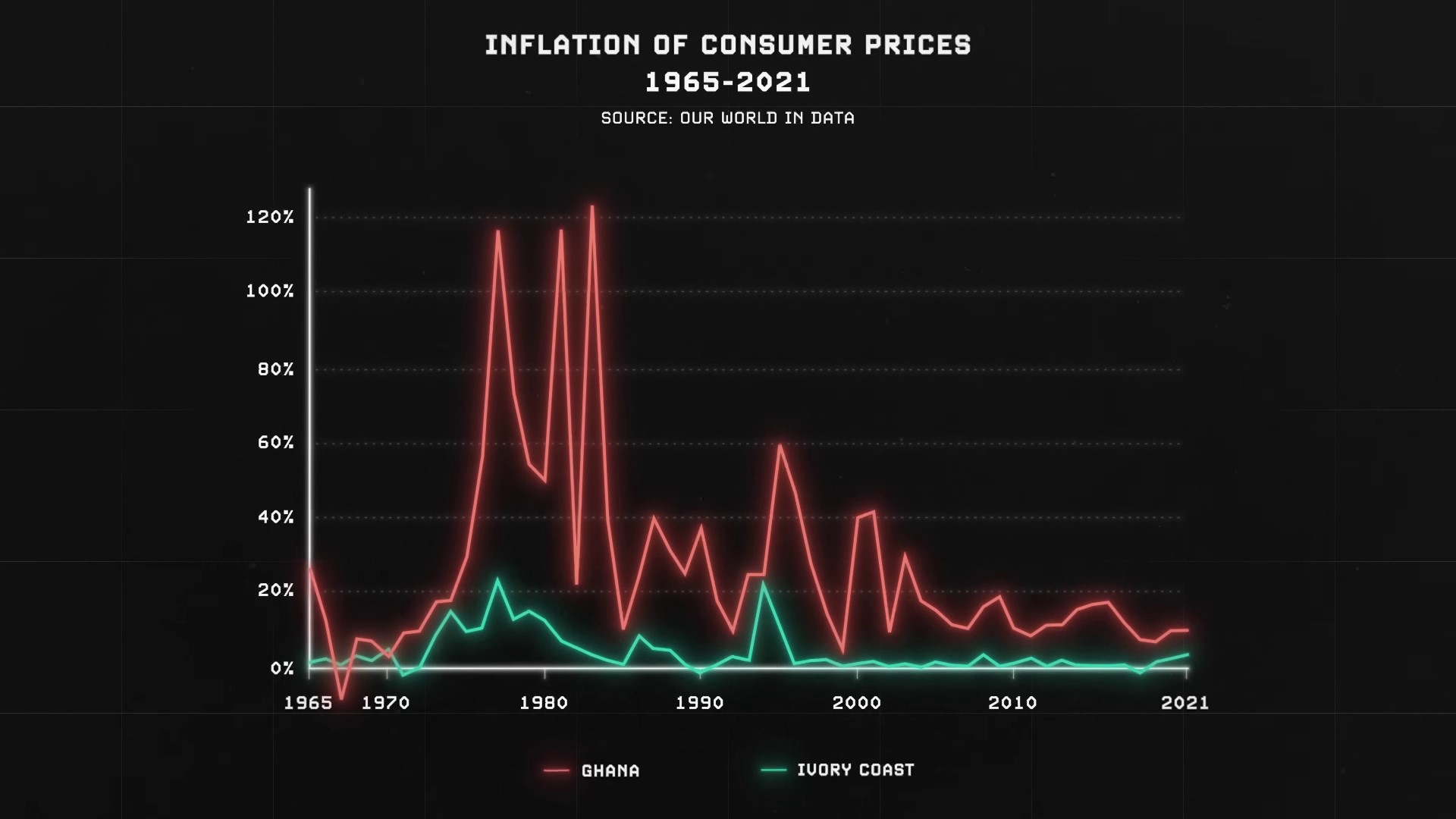

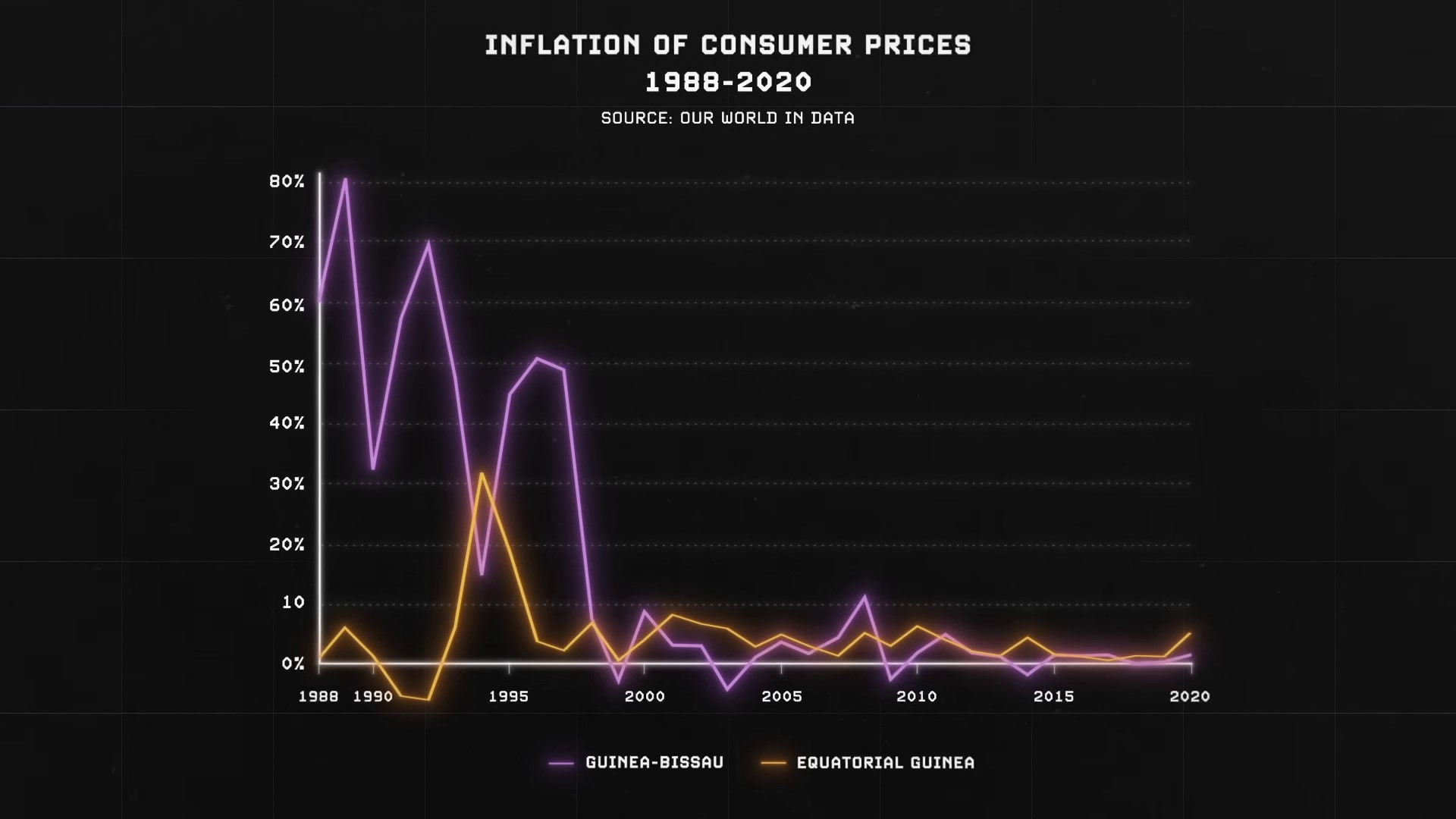

Modern proponents of the ongoing CFA franc system, who are often French or European, argue that the CFA franc being pegged to the euro helps keep these 14 African countries' currencies stable and keeps their inflation rates low compared to their neighbors. For example, the inflation rate in Ivory Coast, which uses the CFA franc, and in Equatorial Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, who joined the CFA franc system in 1985 and 1997 respectively, has been lower compared to neighboring Ghana, which does not use the CFA franc.

Counter-arguments against the CFA franc | 0:24:40-0:30:00

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=1480 The system is not completely devoid of its merits. However, the counter-arguments against the CFA franc, primarily originating from Africans themselves, revolve around a number of noteworthy issues. For one, due to their currencies being directly tied to the Euro, their monetary policies are effectively beyond their sovereignty, and are decided by the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, a bank with vastly different economic priorities from the CFA franc countries in Africa.

The European Central Bank is mainly interested in combating inflation within the highly developed economies of the Eurozone, while most of the underdeveloped African countries using the CFA franc are primarily interested in investing in infrastructure and job creation, policies that instigate inflation. Until 2019, there was a condition that CFA franc members had to keep 50% of their liquid reserves with the French Treasury in Paris for safekeeping. However, even though this policy was reformed in 2019, France continues to print all of the CFA-franc currency in circulation, while the European Central Bank still effectively controls their monetary policy, often against their own interests.

As a result, many people over many decades have argued that without control over their own monetary policy, these Afrique countries have never truly achieved full sovereignty and independence. Hence, their struggle for genuine decolonization continues.

Since the CFA franc countries' exports to the Eurozone and imports from the Eurozone have remained less expensive than elsewhere, it has continually benefited France and Europe financially, while also stifling their own potential for significant export revenue. It has made export-driven economic growth largely unattainable for them and discouraged the development of domestic industries.

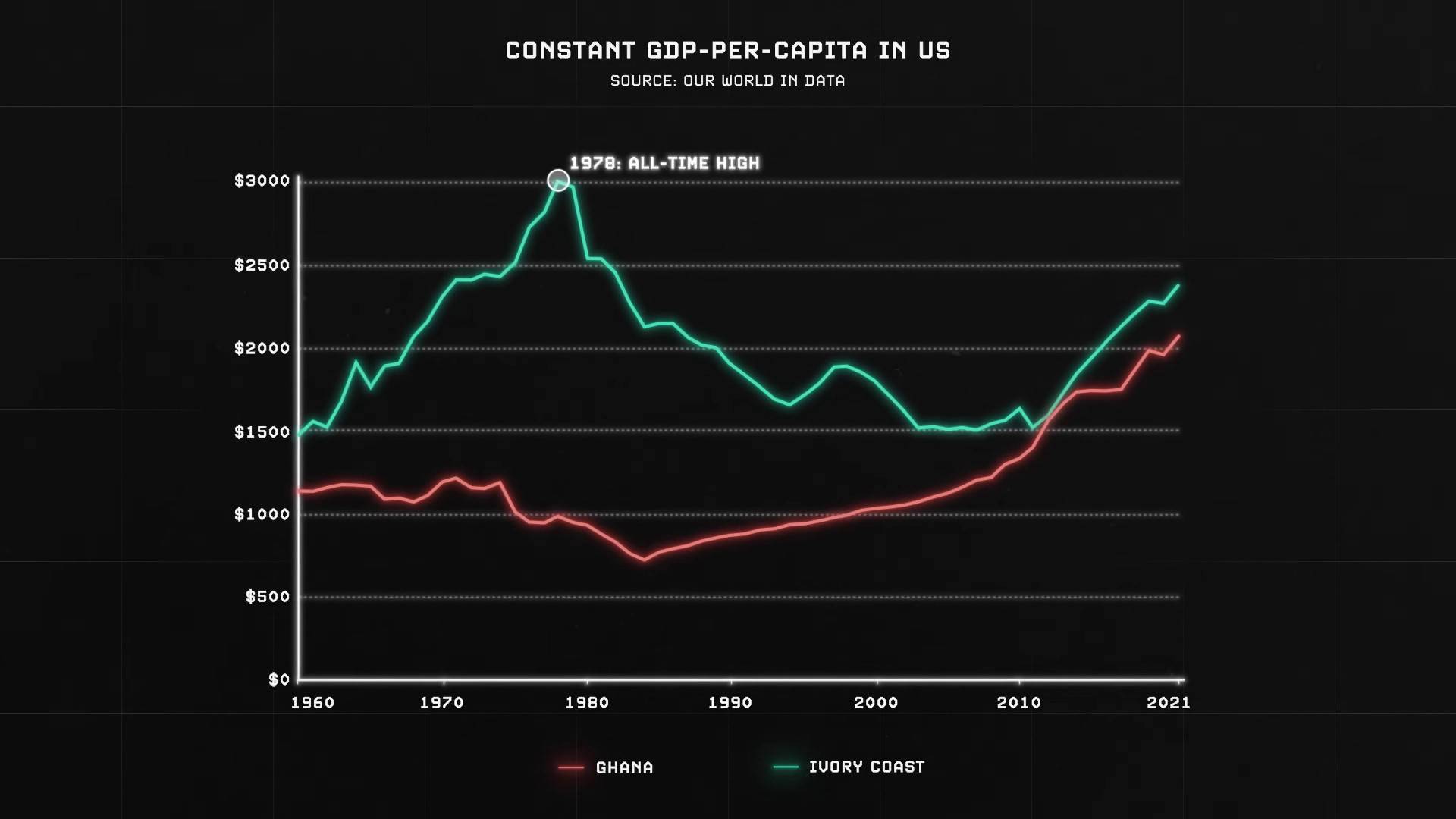

Indeed, while CFA franc users' inflation rates have been lower than those of their neighbors', their economic growth rates have also been significantly less. When comparing the Ivory Coast, which uses the CFA franc, with Ghana, which doesn't, one sees that the Ivory Coast's constant GDP per capita peaked back in 1978 and has never recovered, while Ghana's has consistently risen since 1983. The story is similar with Cameroon’s real GDP per capita, which peaked in the 1980s and has also never recovered.

Due to the consistently low domestic economic growth in these CFA franc countries, it has incentivized the local despotic elites, who are usually closely connected to France, to plunder what little wealth there is for themselves. With the system benefiting France at the expense of the vast majority of Africans for over 60 years, many people believed that European colonialism in Africa had concluded.

In 2007, then French President Jacques Chirac acknowledged the need for change, stating, "We need a measure of good sense. I did not say generosity, but good sense and justice to give to Africans... what we took from them." Chirac recognized as early as 2007 that without major reforms to France's exploitative system in Africa, Africans themselves would eventually rebel against the system, especially with an expected continual rise in the region's demographics into the 21st century.

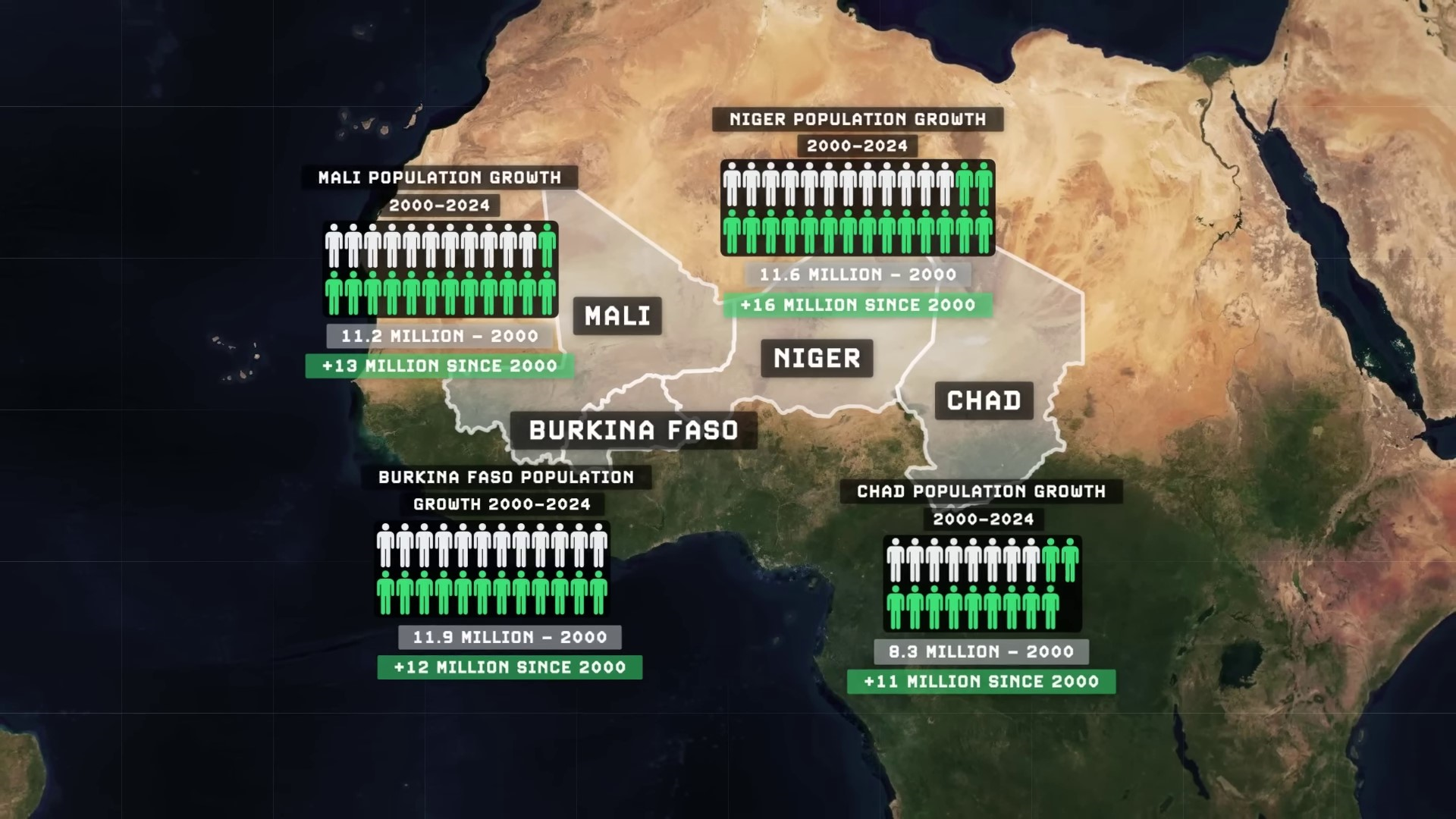

Impact of Climate Change | 0:30:00-0:31:40

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=1800 Countries like Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Chad have all seen their population growth rates exceed 100% since the turn of the 21st century. As their populations rapidly increased, so too did each of their demographic abilities to question and challenge their France-centric economic systems. Moreover, the borders of the nation-states that the French imposed on the Sahel and other parts of Africa were arbitrarily defined and didn't align with the region's ancient and still essential overland trade routes, or its various ethnicities and tribes.

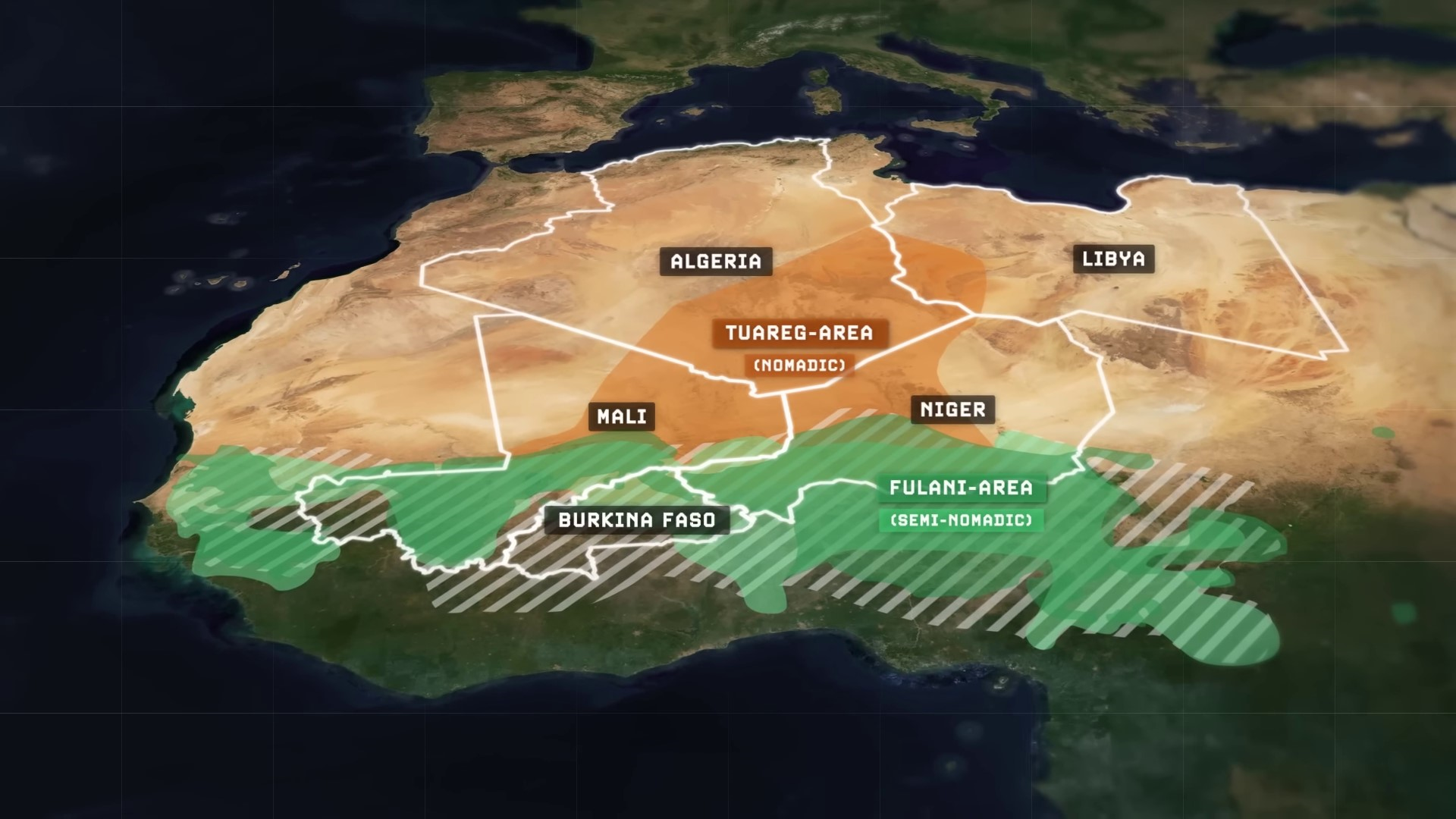

Among these tribes are nomadic herding people like the Tareg, who have never understood the concept of European-style nation-states and do not respect what they consider to be arbitrary borders crossing their ancient herding lands. In the 21st century, problems like climate change have exacerbated the potential for conflict in the region.

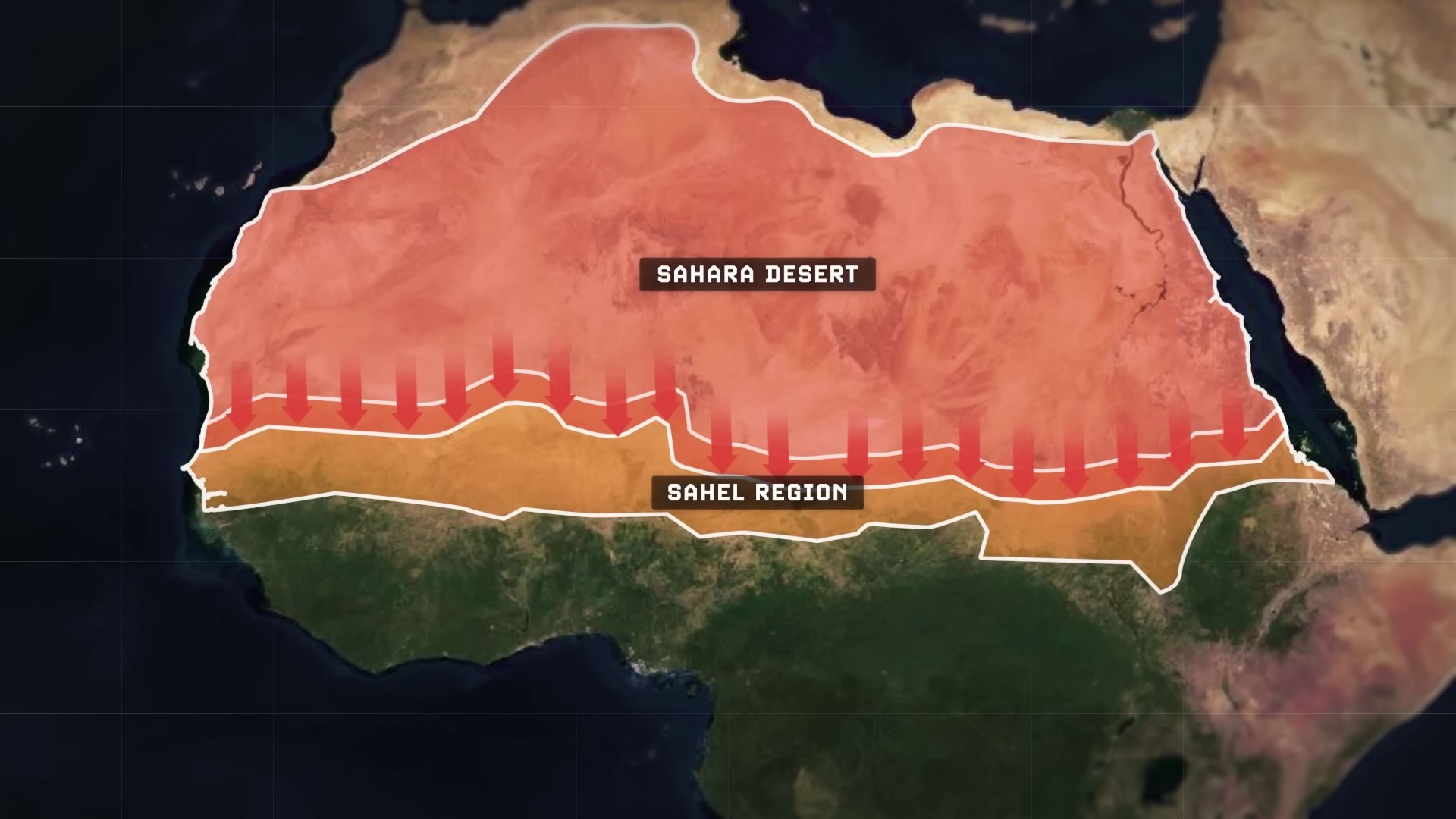

It is estimated that since the start of the Industrial Revolution, Worldwide temperatures have risen by an average of 2 degrees Fahrenheit or 1.1 degrees Celsius, but the average temperature rise in the Sahel region has been estimated to be 50% higher. Since the mid-20th century, increasing populations in the Sahel have led to deforestation for firewood and overgrazing, causing soil erosion and desertification. The Sahara Desert has expanded southward into the Sahel, growing by roughly 8% since 1950. This has forced nomadic people like the Tareg and Fulani to move their herds southward, leading to conflicts with sedentary societies. The Tareg have rebelled against post-colonial states in the region since 1962.

France’s Military Intervention in Mali | 0:31:40-0:36:40

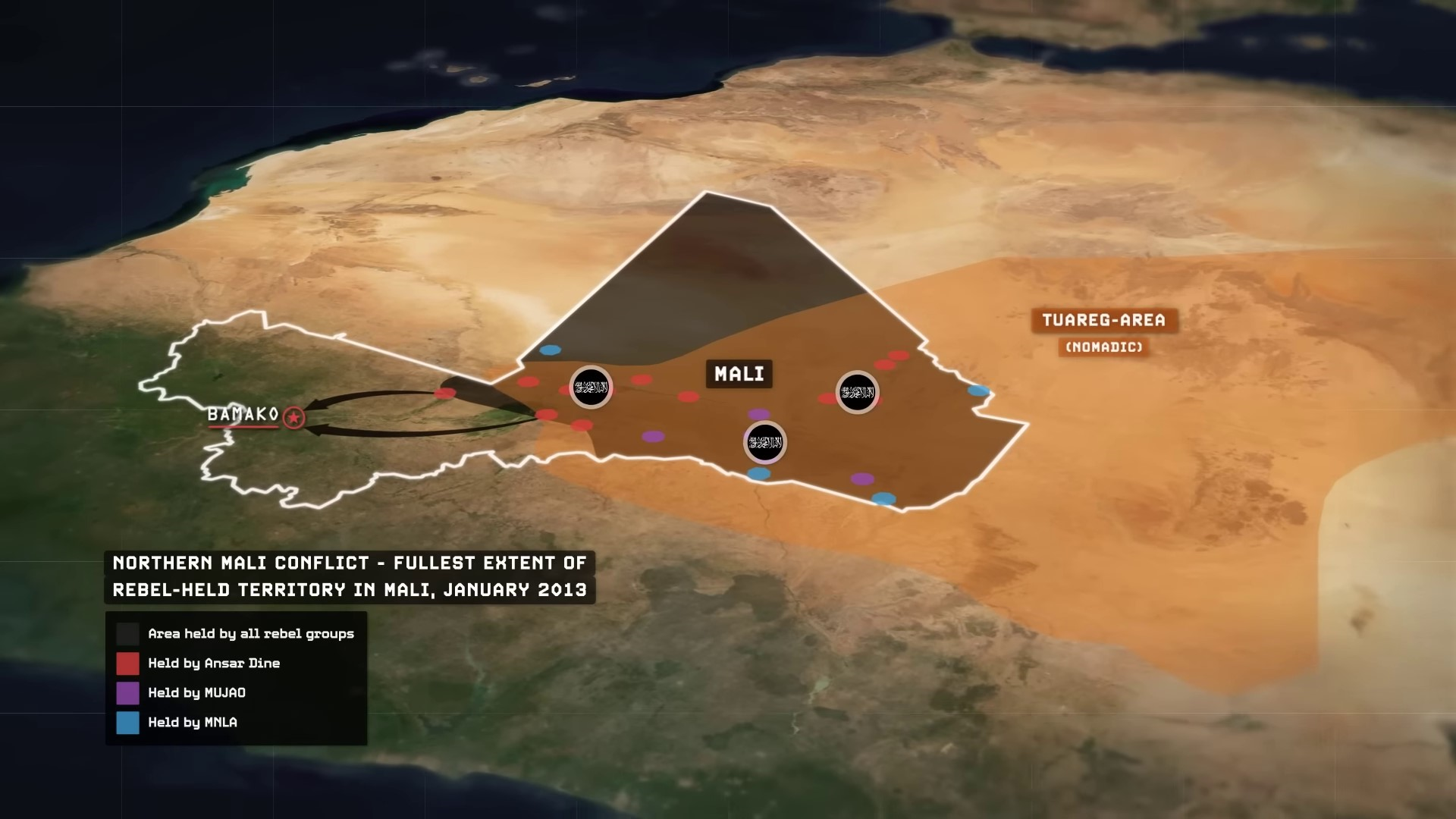

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=1900 In 2012, a major Tarek rebellion in northern Mali led to the declaration of independence of the state of Azawad, which was later co-opted by Islamist forces like Al-Qaeda. Paris was concerned that Al-Qaeda-backed militants were on the verge of expanding from northern Mali and toppling the entire country.

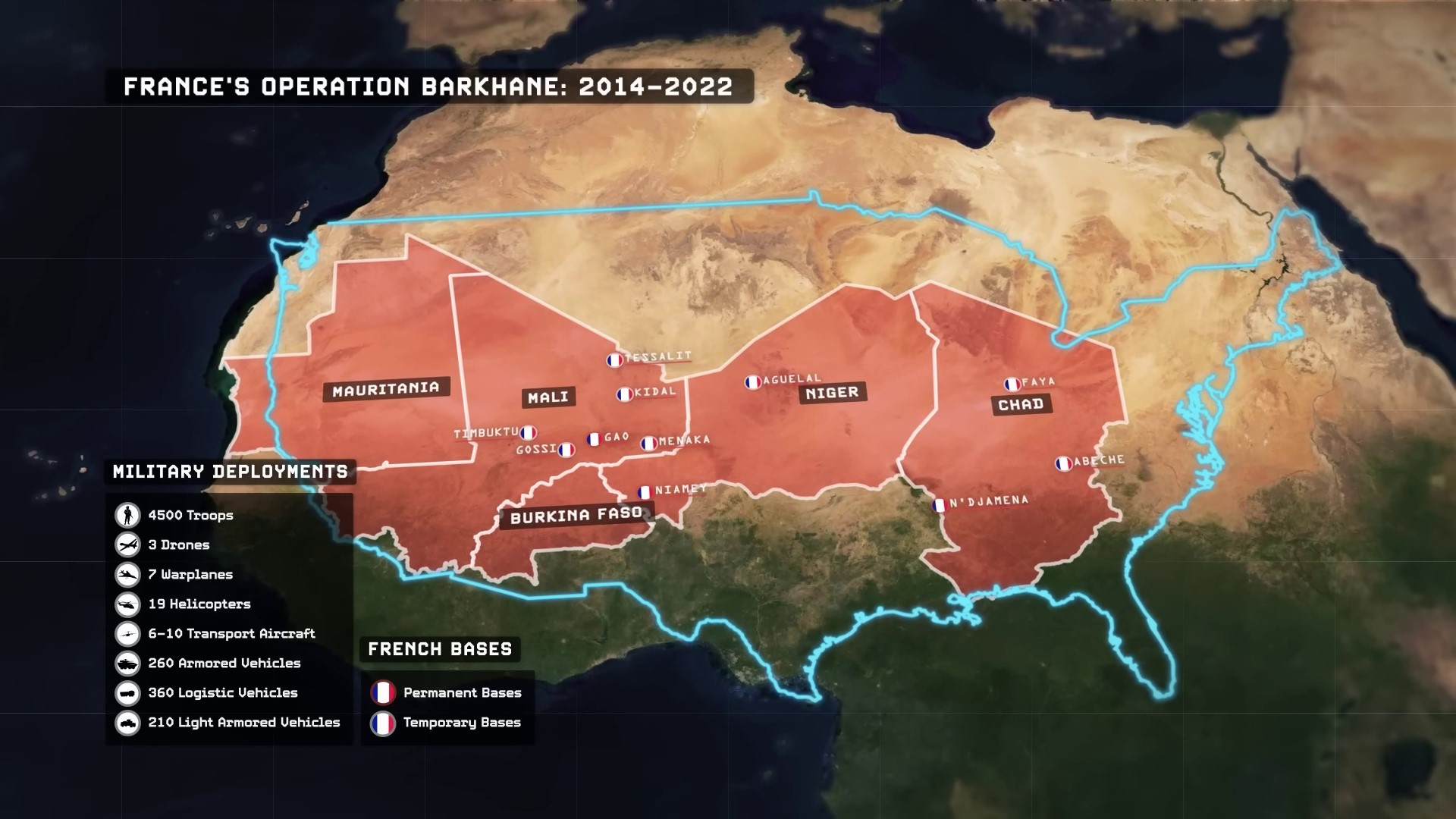

In 2013, France launched a major military intervention in Mali to beat back rebels and restore control to the Malian government. This intervention aimed to prevent the establishment of a jihadist state like the Taliban’s Afghanistan on Europe’s doorstep. The French deployed over 5,000 troops and conducted a long counter-insurgency campaign in the Sahel region to push back against Islamist rebels and protect France’s neocolonial interests, including uranium mines in Niger and the CFA franc financial system. The operation, codenamed Operation Barhain, involved French troops and troops from Sahel states like Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Mauritania.

The Sahel region in Africa faced a growing Islamist insurgency that spread from Mali to Burkina Faso and Niger, leading to a significant increase in terrorism-related deaths. The French-led counterinsurgency operation struggled to contain the violence, causing frustration among local populations. Anti-French sentiment escalated, culminating in a military coup in Mali in 2021 and the expulsion of French troops. This highlighted underlying tensions over neocolonial practices and raised questions about France’s true intentions in the region.

The Russian Mercenary Wagner Group in Africa | 0:36:40-0:46:00

https://youtu.be/fiD24uEvY1U?t=2200 The Russian mercenary Wagner Group, led by Evgeny Purgoshin, filled the vacuum left by France in Mali by offering troops to combat Islamist insurgencies. They expanded their operations in Africa from 2017, assisting conflicts in Sudan and the Central African Republic. Wagner's success in the CAR led to contracts with other African nations. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Wagner capitalized on anti-French sentiments in the Sahel. Despite accusations of war crimes, Wagner presented itself as an alternative to French influence. Following Purgoshin's mutiny and death, the Wagner Group in Africa was restructured as the Afrika Korps, now under the control of the Russian military intelligence service, GRU. Anti-French coups in Burkina Faso and Niger further solidified Wagner's presence in the region.

The newly formed Afrika Korps has been quick to offer similar deals to those they have with Mali, known as regime survival packages. The African production of their operations has become a major objective of the Russian Afrika Korps, which desires to smuggle the gold out of these major mines across the region's porous borders back to Russia. This is a means to covertly evade Western sanctions and fund their war effort in Ukraine. In addition to securing Russian access to raw materials, the Afrika Korps is tasked with disrupting French access to the same resources in the region. Leaked documents have revealed Afrika Korps' plans to exploit their budding relationship with Niger to threaten France's continued access to uranium mines, which power more than 12% of France's electricity.

Three main anti-French junta-led Sahel states - Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger - have all either welcomed the Afrika Korps into their countries already or, as in Niger's case, are in the process of doing so. All French troops have been expelled from these countries and relations with France have been severed. These states have announced their new military defense pact, known as the Alliance of Sahelian States. In January 2024, they announced their formal withdrawals from the ECOWAS regional alliance system. In February 2024, the Alliance of Sahelian States began high-level discussions about further withdrawing from the CFA franc system.

The new leader of Niger insisted that for decolonization from France to be completed and for Niger to achieve its full sovereignty, it needed to regain its full monetary sovereignty from Paris, which it has never truly enjoyed for centuries now. The new leader of Burkina Faso vowed that his country will never again be colonized or dominated by Europeans. They have discussed replacing the CFA franc with their new mutually independent currency. Successful or not, their defiance of France has already captivated millions of other Africans across the rest of the CFA-Franc system who share similar grievances against French exploitation.

It was only a month after Niger's successful coup that another successful coup occurred in Gabon, which finally toppled the 56-year old pro-French dictatorship dominated by the Bongo family, initially appointed by Charles de Gaulle himself. With the rise of anti-French sentiment sweeping across the region of Franc Afrique, it appears the wheels of change are turning. How this will impact the future remains uncertain.

In many ways, it has been a long-awaited reckoning for France’s exploitative project in Africa. Much of this can be traced back to the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya. This intervention against Gaddafi’s army destroyed it, opening the door for the Libyan rebels to rapidly overthrow Gaddafi and murder him. The ensuing chaos led to an influx of experienced Tarek mercenaries in Northern Mali who were hired by Gaddafi. This, in turn, led to a new Tarek rebellion against the central government in Mali. The French were then forced to send 5,000 troops into Mali to push back the Tarek rebellion which became influenced by Al Qaeda. This intervention effectively became France's own Afghanistan or Iraq, with thousands of French troops remaining in place, conducting counterinsurgency operations as groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS continued spreading. This transformed the region into the epicenter of global terrorism which the French were incapable of stopping. The situation eventually evolved into France’s forever war as the territorial cores of ISIS and Al Qaeda shifted from the Middle East to the Sahel.

However, due to the violent and controversial nature of discussing how such infamous organizations as Al-Qaeda and ISIS have established themselves in the Sahel, and how the French operations against them have fared, this video is likely to be demonetized and age-restricted by YouTube's algorithm.

On the bright side, you can find more about this on Nebula, where you will find a 40-minute segment covering how ISIS and Al Qaeda spread rapidly across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, and how the French military waged its campaigns against them. You'll also find videos covering the wars in Libya, the rise and fall of ISIS as an organization in Iraq and Syria, the US war in Afghanistan, and the civil wars in Syria and Lebanon.