Why Norway is Becoming the World's Richest Country - RealLifeLore

RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Norway's Population and Land Area | 0:00:00-0:00:55

- Challenges of Norway's Terrain | 0:00:55-0:02:55

- Norway's Maritime Culture and Economic Development | 0:03:35-0:07:35

- Norway's Economic Growth Through Hydroelectric Development | 0:07:35-0:13:35

- Norwegian Oil, Natural Gas, and Emergence as Petrostate | 0:13:35-0:26:35

- Norway's Sovereign Wealth Fund, Energy Approach, and Influence in Europe | 0:26:35-0:38:15

- China's New Export Restrictions on Ore | 0:38:15-0:38:35

https://youtu.be/RO8vWJfmY88

Norway's Population and Land Area | 0:00:00-0:00:55

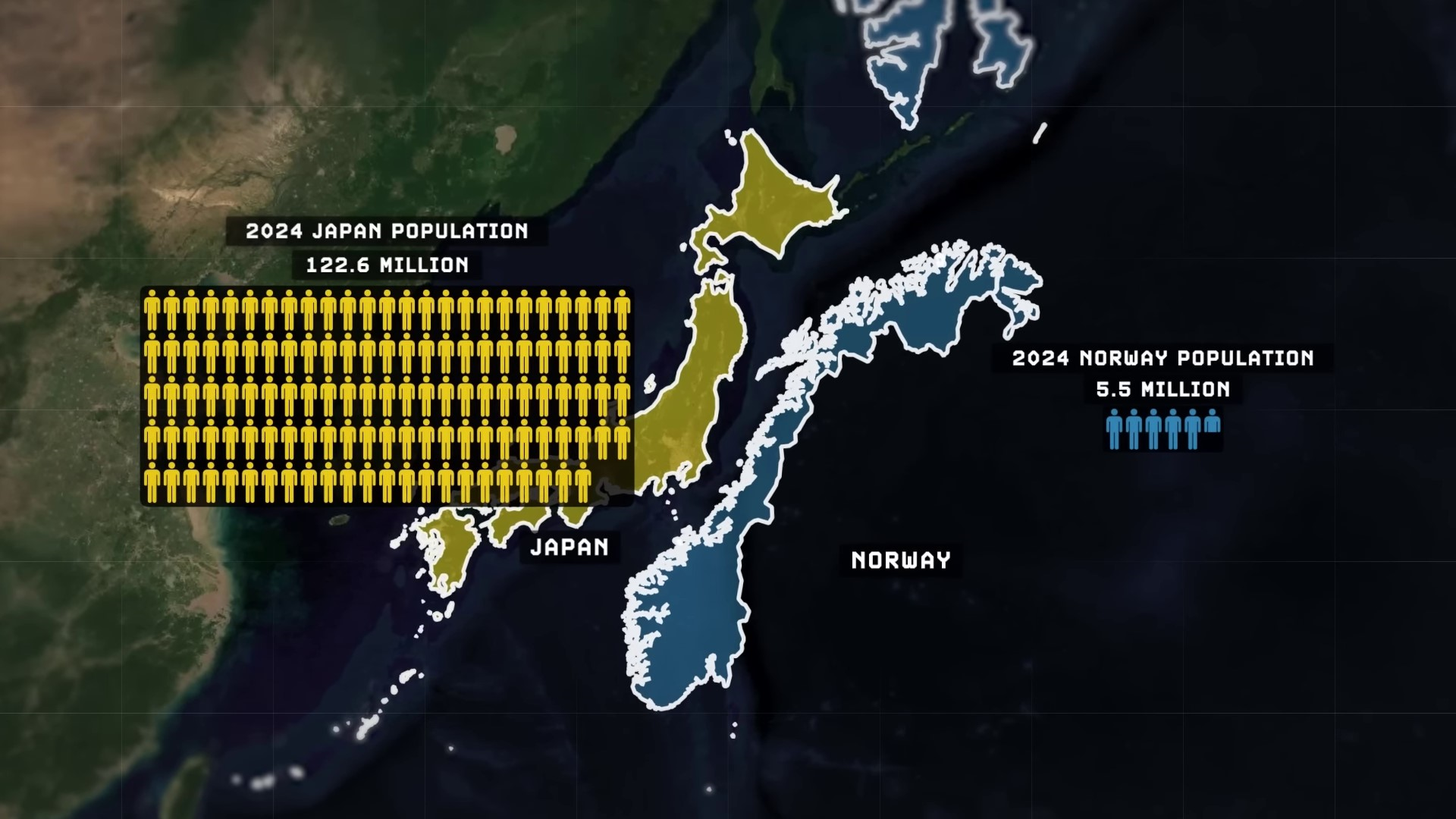

Norway has a small population compared to city-states like Singapore and Hong Kong, but it is large in land area with about 385,000 square kilometers. Despite its size, Norway is sparsely populated and considered one of the most empty countries in the world. The northern half of the country extends beyond the Arctic Circle and has harsh terrain with a thin layer of topsoil above bedrock.

Challenges of Norway's Terrain | 0:00:55-0:02:55

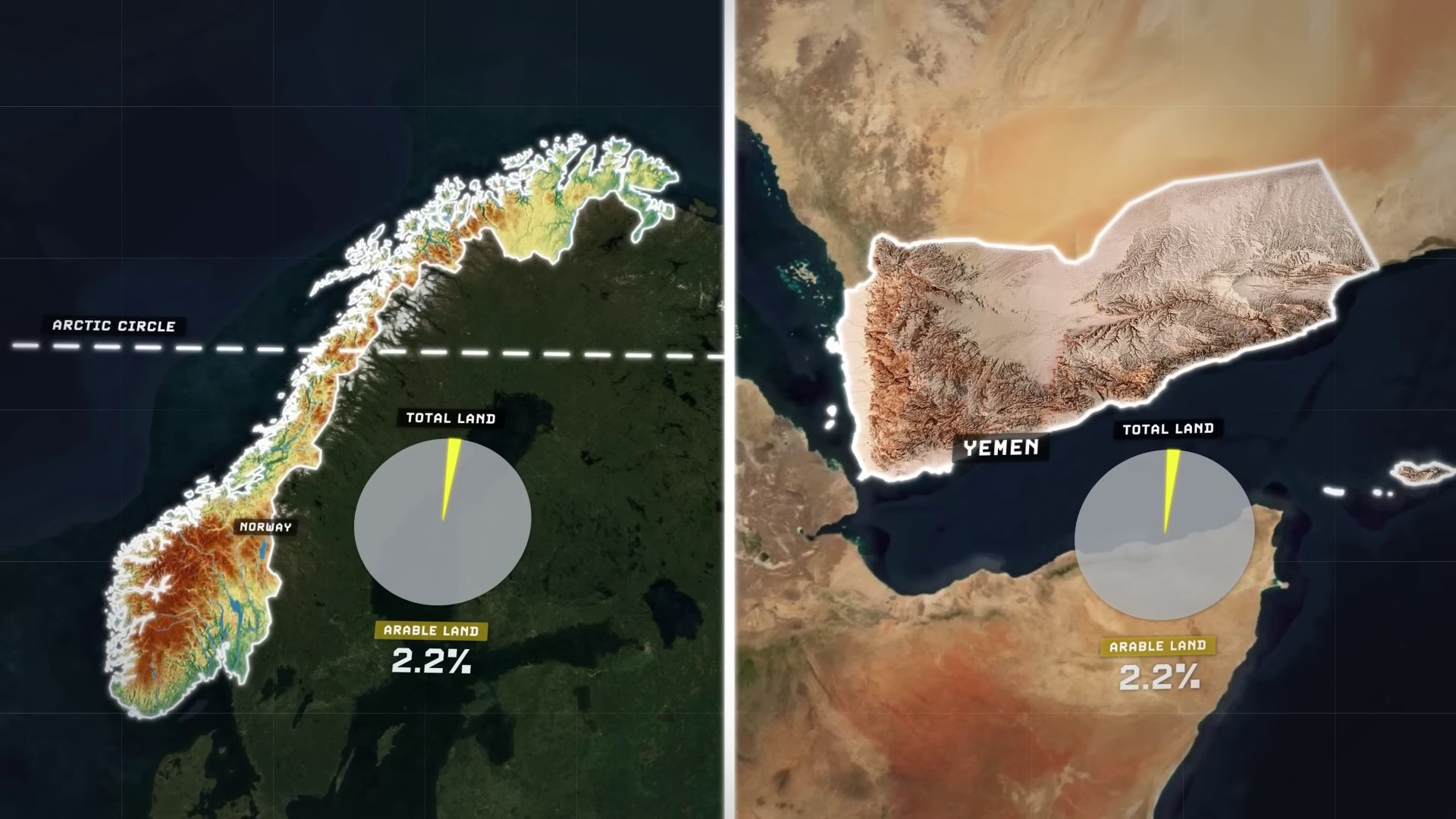

Norway's mountainous and rugged terrain with a short growing season limits its arable land to only 2.2%, similar to Yemen. The scattered arable land in small valleys makes large, integrated farms impossible, unlike the US where farms are more efficient and productive. This hinders Norway's ability to sustain a large population despite its vast overall land size.

Throughout Norway's history, there have been expectations and assumptions that the country should naturally be poor. However, the discovery of oil in the late 1960s did not make Norway rich; it simply enhanced its existing wealth. Contrary to popular belief, Norway has been relatively wealthy for most of its history, despite its challenging geography for agriculture. Other geographic factors beyond agricultural potential have played a role in determining the fate of nations.

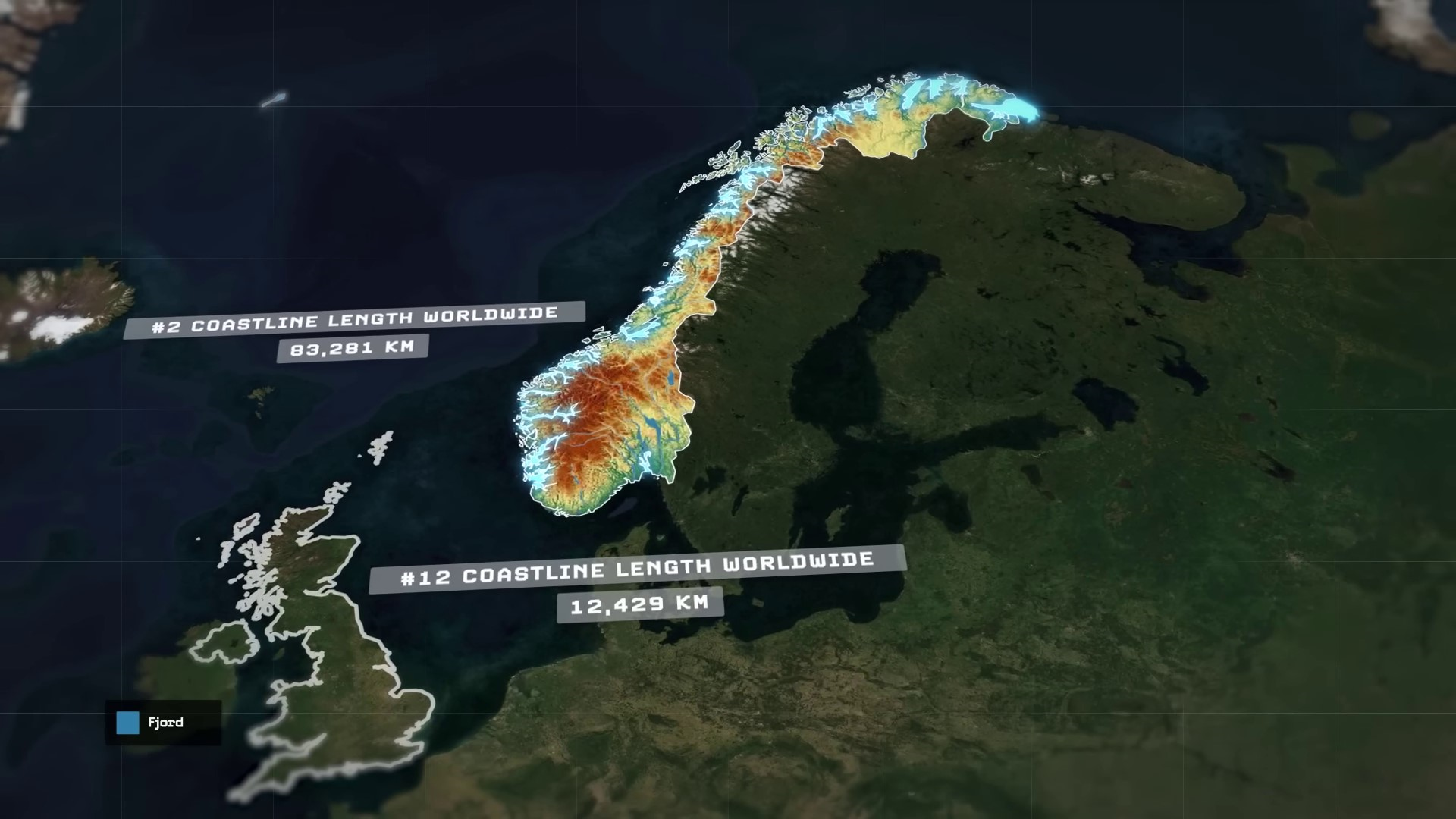

Norway's difficult terrain made land transportation challenging for thousands of years. The jagged fjords along the coast, while initially a hindrance, turned into a blessing as Norway now boasts the longest coastline in Europe. The coastline is more than six and a half times longer than the United Kingdom, making trade and travel easier across the country's territory.

Norway's Maritime Culture and Economic Development | 0:03:35-0:07:35

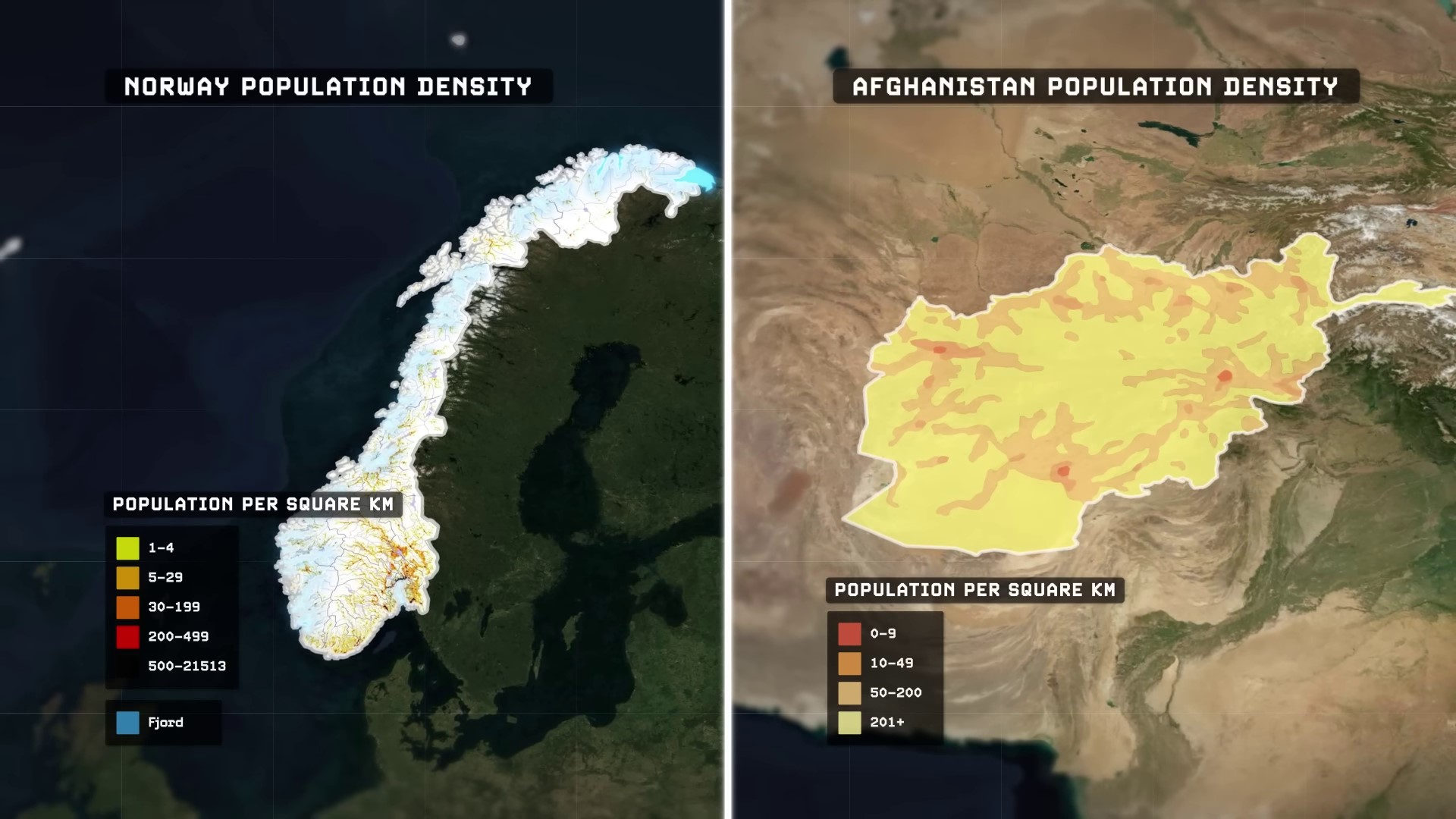

In fact, the enormous size of Norway's coastline, due to its many fjords, makes it the second longest in the world, exceeded only by Canada. This resulted in the small Norwegian population being scattered in clusters throughout the mountains and fjords as the nation evolved. A scenario not unlike other mountainous societies such as Afghanistan or Persia. However, unlike these inland Eurasian societies, the scattered populations of Norway had easy and immediate access to the global ocean due to the fjords that extend deep into the country's interior. This geographical feature encouraged a maritime culture from very early on, facilitating quick sea travel between settlements and allowing traders easy access to Norway's vast forests and lumber resources.

Although Norway does not possess the largest forests in Europe – those honors go to countries like Russia, Finland, Sweden, and even France -- throughout the Age of Sail and before the advent of railroads, Norway's lumber industry was the largest in Europe. This was primarily due to the relative ease of access to its inland forests via the fjords. Norway's timber could be harvested within the interior, then efficiently transported downstream towards the fjord-side settlements and sawmills, where it could be refined and exported cheaply to global markets.

Until the late 19th century, when railroads unlocked the lumber potential of countries with larger forests, such as Russia, Finland, and Sweden, this geographical advantage positioned Norway as Europe's foremost lumber powerhouse. Furthermore, the country's maritime culture led to the construction of a world-class merchant fleet, making Norway home to the fourth largest merchant marine fleet by the 20th century.

The nature of Norway's widely distributed but interconnected and low-density population also fostered a sense of shared identity and cooperative behavior in ship construction for communal benefit. Over time, this led to a decentralized distribution of wealth and ownership in Norway, in stark contrast to the emergence of a centralized capitalist class in other countries like France and Britain.

Such early cooperative behavior integrated into the national economy and shaped various sectors including agriculture, forestry, maritime insurance, and fishing, in addition to banking, which became dominated by cooperative credit unions by the 19th and 20th centuries.

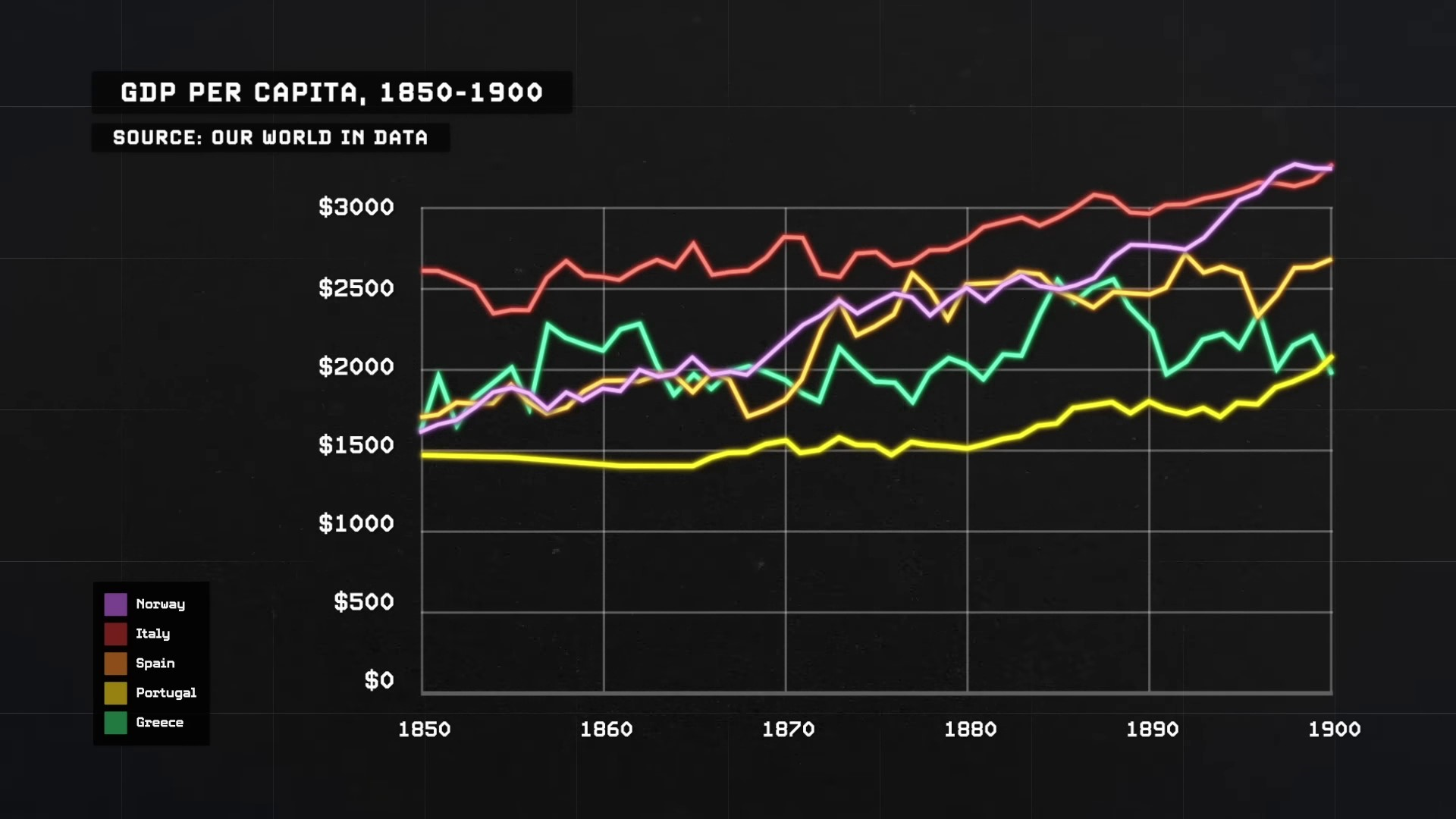

Despite being considered a poor region in the 19th century, Norway was actually doing quite well for itself. By the 1850s, its GDP per capita exceeded that of most of Eastern Europe, including Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, and by the 1880s, it surpassed most of Southern Europe, including Portugal, Spain, and Greece. By the onset of the 20th century, Norway's economy even overtook Italy's, and by 1938, on the eve of World War II, despite having not yet discovered its oil resources, Norway continued to experience economic growth.

Norway's Economic Growth Through Hydroelectric Development | 0:07:35-0:13:35

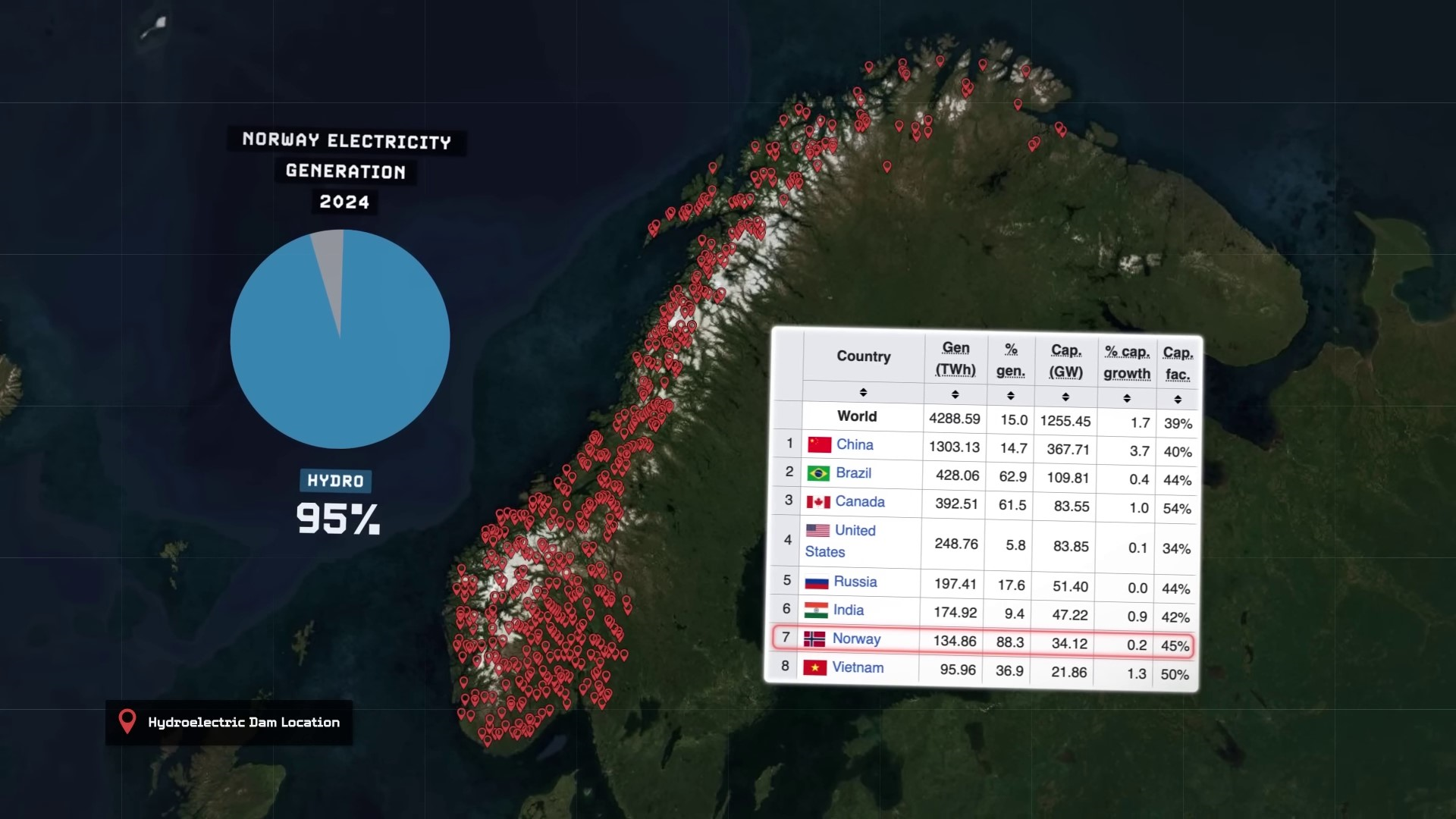

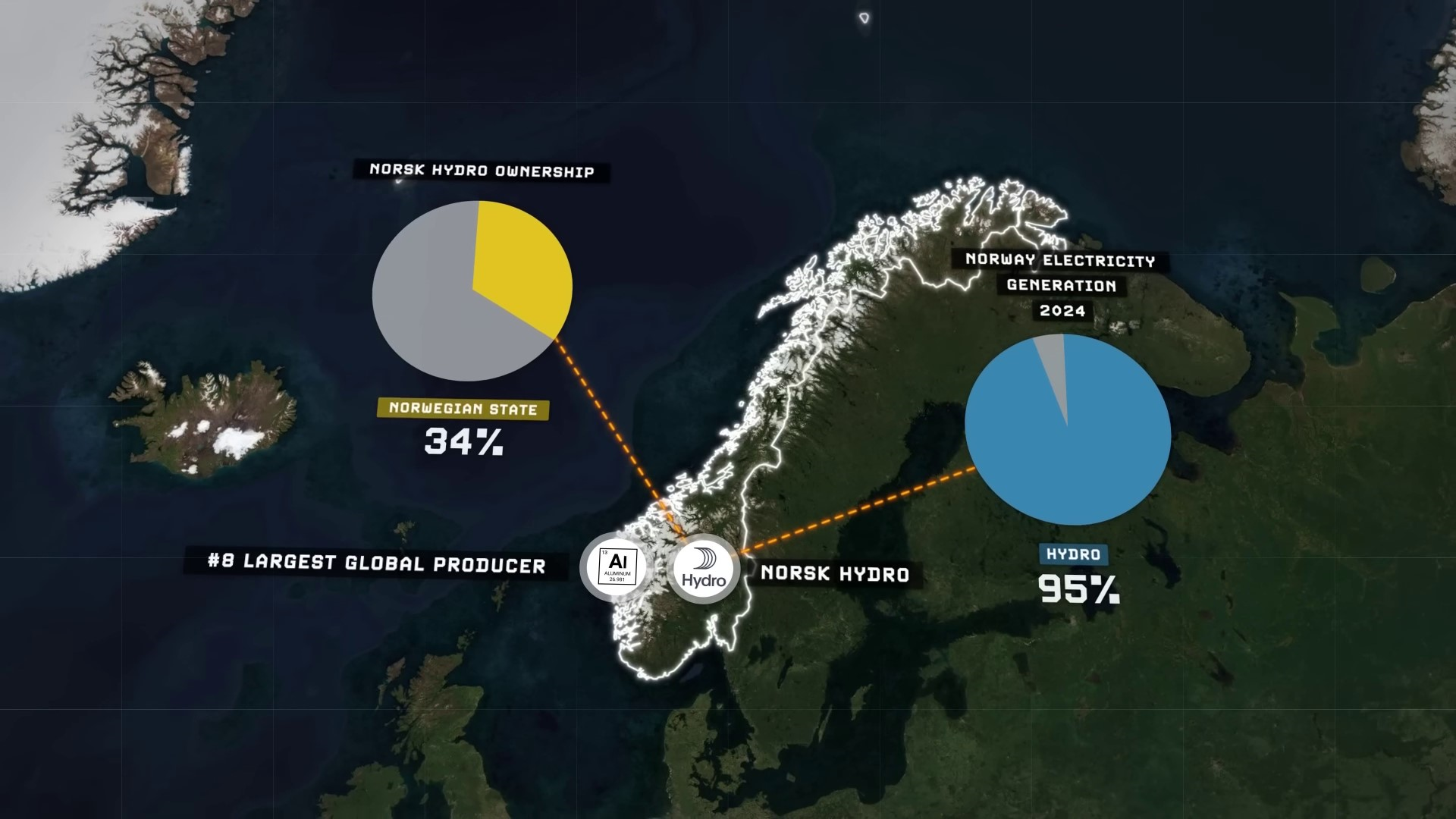

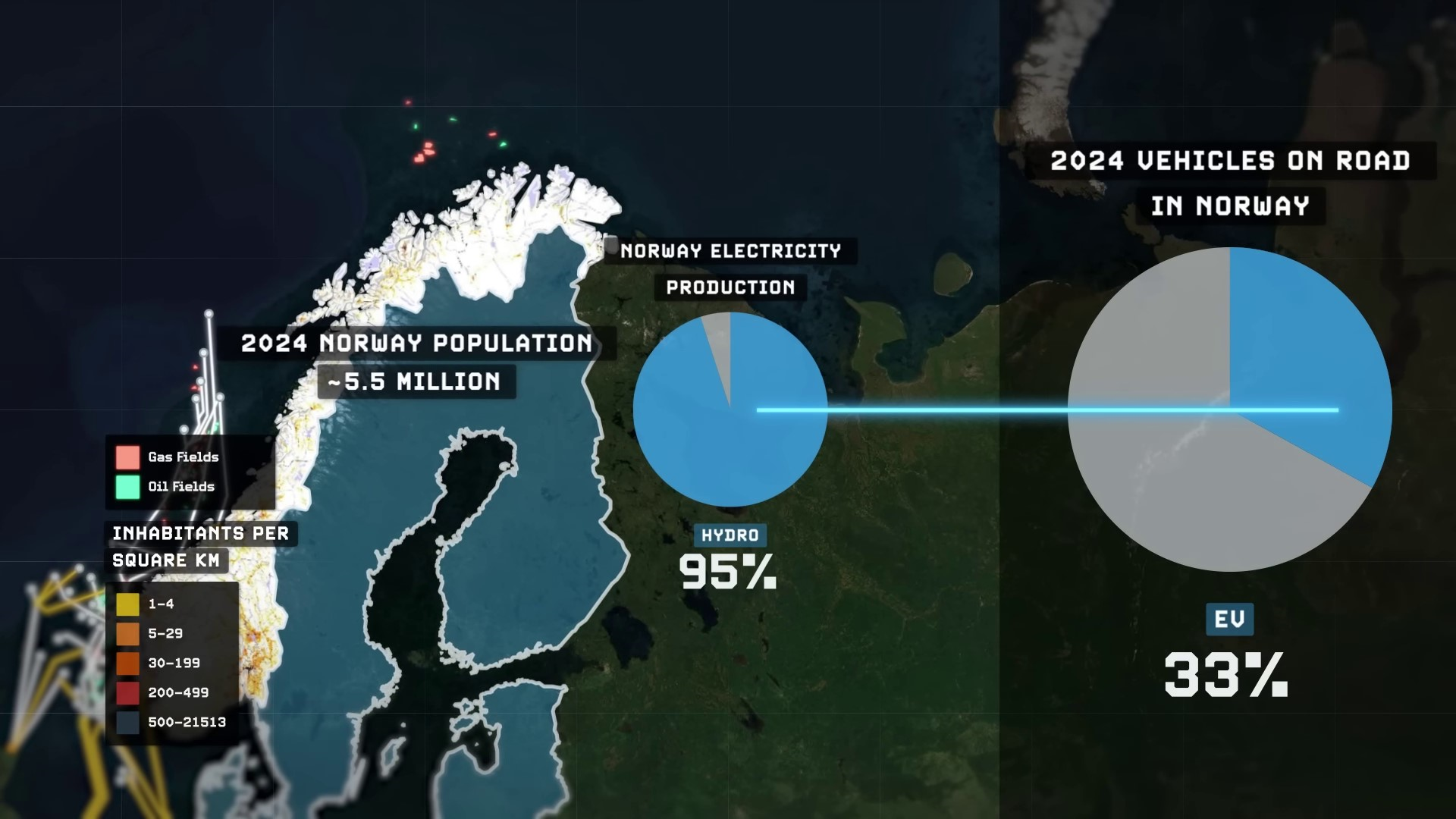

Norway's rapid economic growth between 1900 and 1938 was fuelled by the development of modern advanced water turbines and hydroelectric dams, capitalizing on the country's abundant water resources. By inviting foreign companies to build hydropower stations, Norway utilized its high hydroelectric power potential, satisfying 95% of its electricity demand. This facilitated swift industrialization and electrification, with Norway becoming a significant producer of refined aluminum. However, the industry became dominated by foreign companies, prompting Norway to gradually take control over its resources to safeguard national interests.

To prevent complete foreign control, but still retain control over their own resources, Norway decided to adopt a pragmatic and long-term approach to the hydro industry that would later influence its handling of the oil and gas industry. Norway established rules that required foreign companies investing in Norwegian hydro to secure and maintain the resources themselves, leading to over 90% of Norway's hydro capacity being publicly owned by the state today.

This is why Norway was already a wealthy, heavily industrialized, democratic, and low-corruption state by the late 1950s when interest piqued in the country's potential offshore oil and gas fields. At that time, few believed that there were significant oil or gas resources, particularly within the shallow, submerged part of the European continental shelf beneath the North Sea. This area had, geologically speaking, only recently been submerged a few thousand years prior at the end of the last ice age. In a letter written by the Geological Survey of Norway in 1958, it was concluded that the possibility of any oil or gas resources being discovered on the Norwegian part of this continental shelf was highly unlikely.

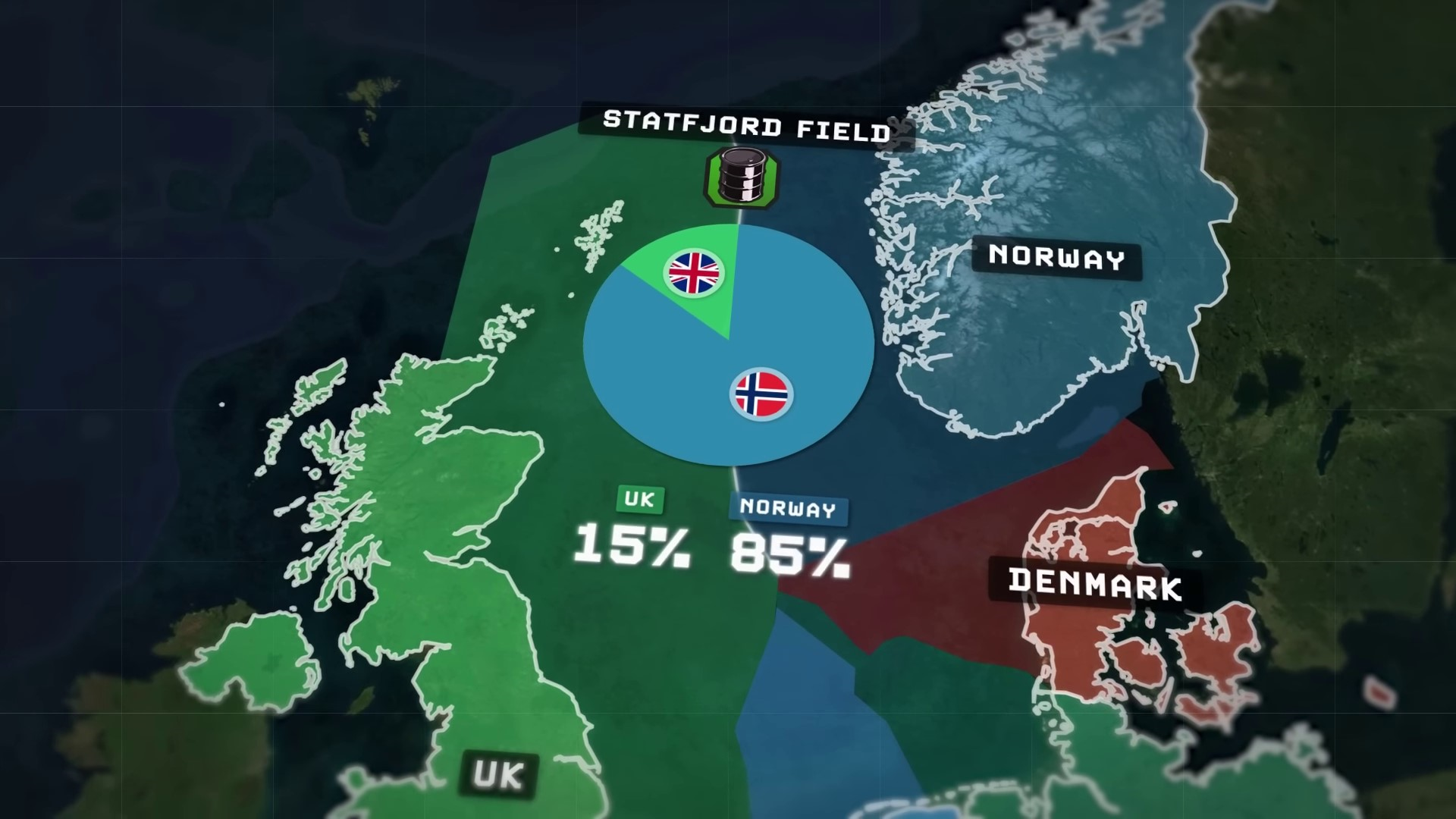

However, in 1959, just a year after the letter was written, a significant natural gas discovery was made in the vicinity which renewed interest and curiosity in the potential for further gas and possible oil discoveries beneath the unexplored North Sea. Three years later, in 1962, American petroleum major Phillips became the first to submit an application to the Norwegian government to explore oil and gas resources within their section of the North Sea. The only issue at that time was the unclear maritime boundaries within the North Sea between the surrounding nations. Fortunately for Norway, the UK government, eager to explore and drill in 1965, swiftly agreed to divide the continental shelf beneath the North Sea based on the median line principle—a geographical line running down the center of the North Sea between the UK's and Norway's territories.

Norwegian Oil, Natural Gas, and Emergence as Petrostate | 0:13:35-0:26:35

Decades later, a hasty yet savvy calculation benefited Norwegians by incorporating thousands of islands in defining the median line, leading to additional oil revenue from the Statfjord oil field. The Norwegian government granted exploration licenses to foreign companies, which resulted in the discovery of the Balder field in 1967. The Ekofisk field was identified by Phillips in 1969, marking a significant moment in Norway's history.

Norway's oil and gas industry was initiated with the Ekofisk oil field discovery in 1971, which in turn led to more significant finds across the Norwegian continental shelf. In 1996, the Troll A offshore oil platform's transportation was a headline-making event, as it was the heaviest and tallest object ever moved by humans. The state-owned oil and gas company Statoil, now known as Equinor, was set up by Norway, and maintains ownership stakes in production licenses. Norway's expertise in shipbuilding assisted in mastering offshore and subsea projects, leading to the establishment of companies like Subsea 7. Today, Equinor continues to be a vital player in the industry.

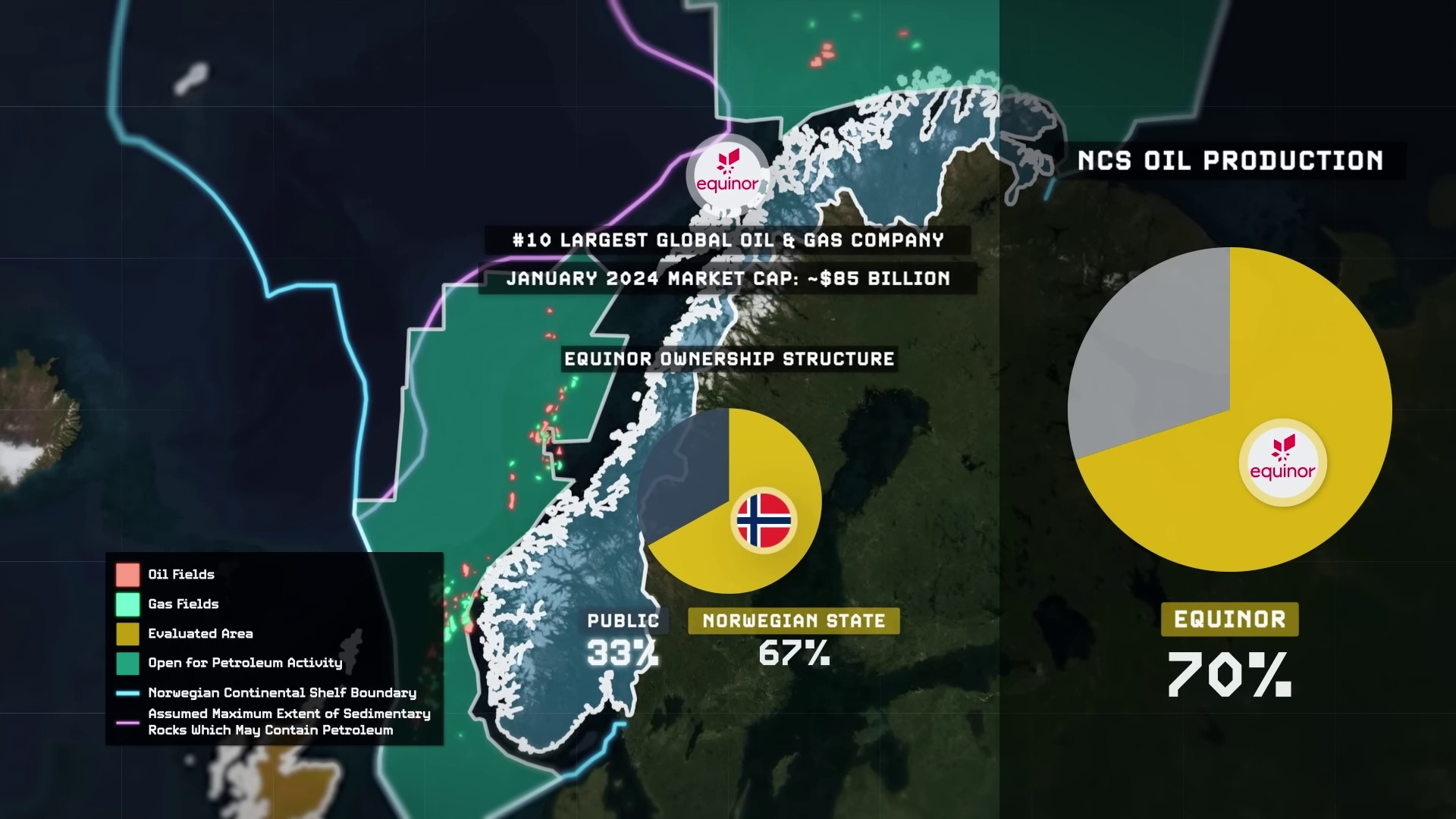

Norway's foresight in directing Equinor has resulted in its global prominence as the tenth largest oil and gas company, boasting a market cap of $85 billion. Equinor is responsible for 70% of oil and gas production on the Norwegian continental shelf, with the Norwegian government owning a 67% stake. The remaining 33% of the company's shares are publicly traded on global stock exchanges. Norway now holds the largest oil reserves in Europe, excluding Russia.

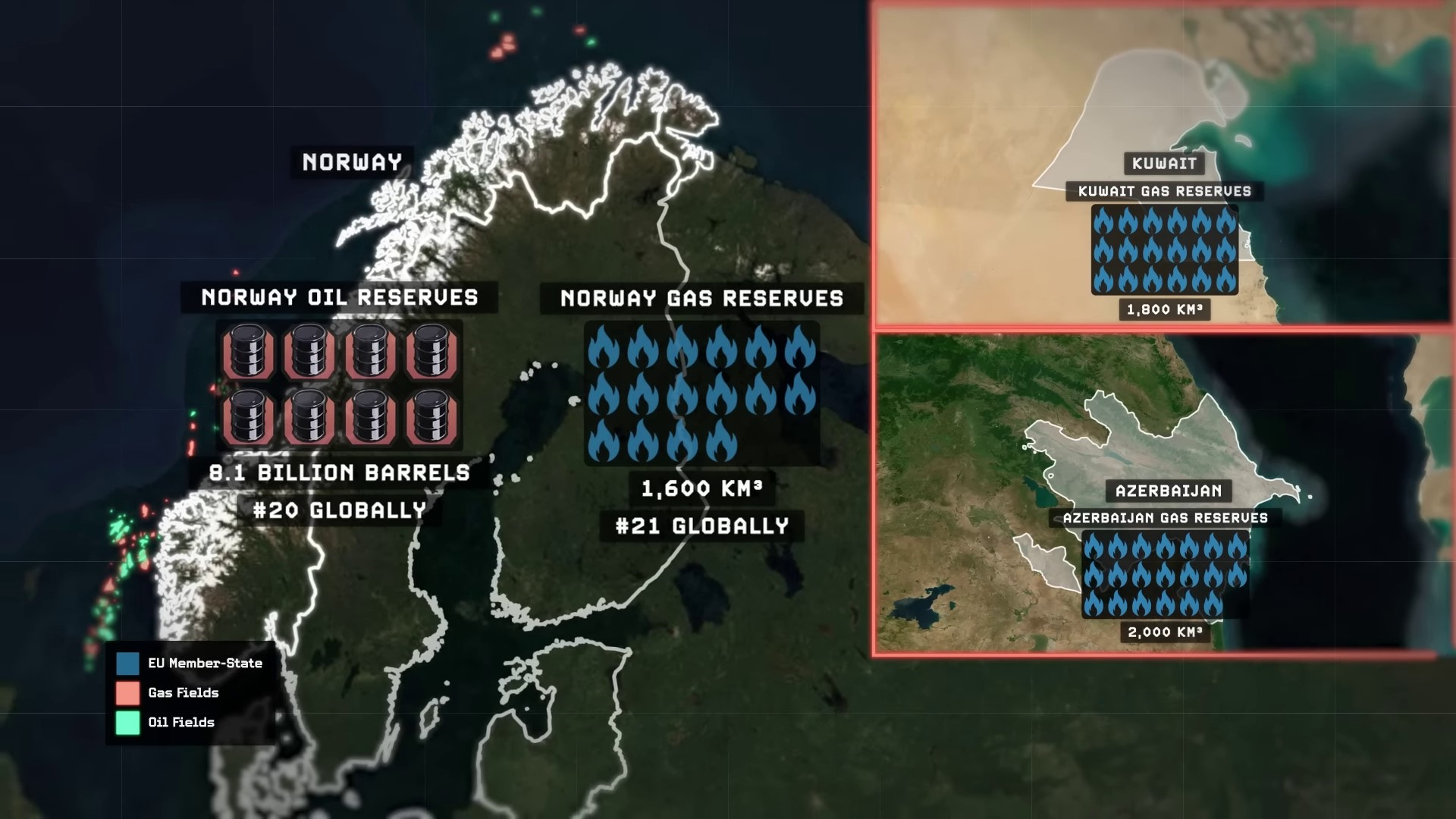

It ranks 20th worldwide and holds volumes similar to those of former OPEC members, Angola and Ecuador. Norway's reserves are more than three times the size of those in the UK, which occupies the next highest European spot across the North Sea.

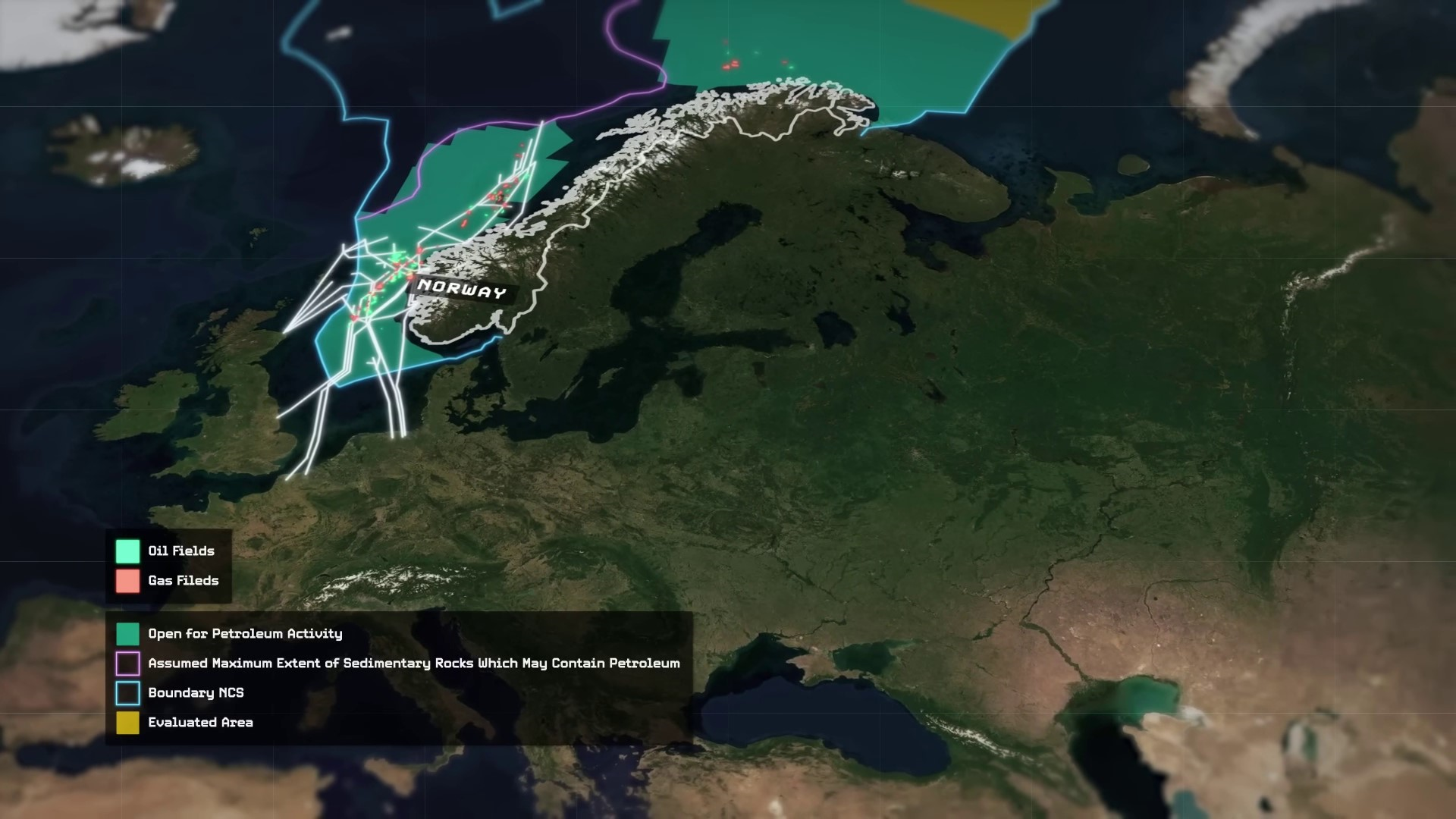

Norway has the largest natural gas reserves in Europe bar Russia, and ranks 21st globally. These reserves are comparable to countries like Kuwait and Azerbaijan. Due to its close proximity to the European Union market, Norway has an immediately accessible export market for its natural gas.

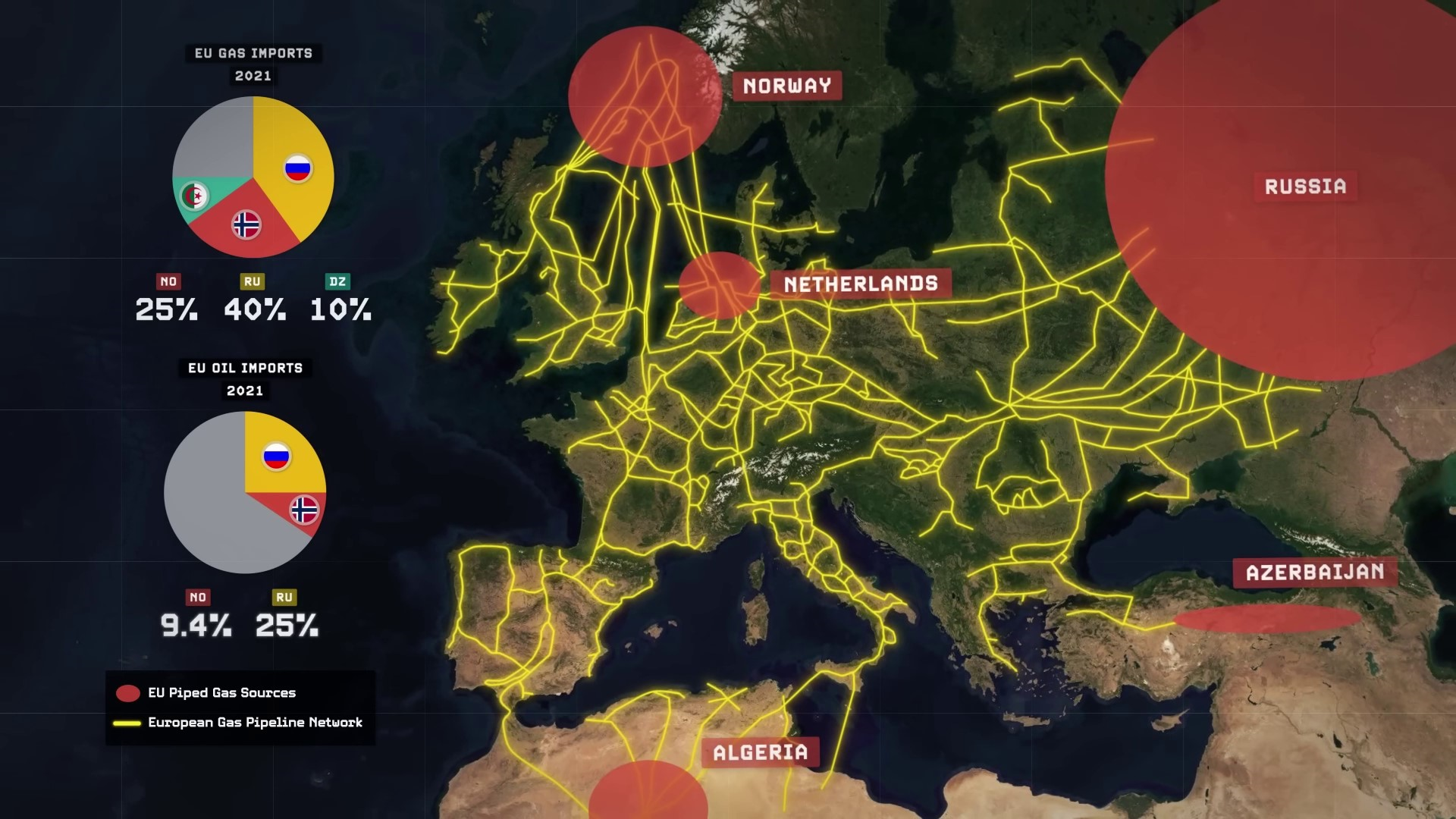

The European Union has had to import most of the oil and gas they consume due to limited domestic resources. While importing oil is simpler, natural gas presents a challenge due to its gaseous state, making it more challenging and expensive to export compared to oil. This is because gas has a larger volume and isn't economically viable to transport using container vessels.

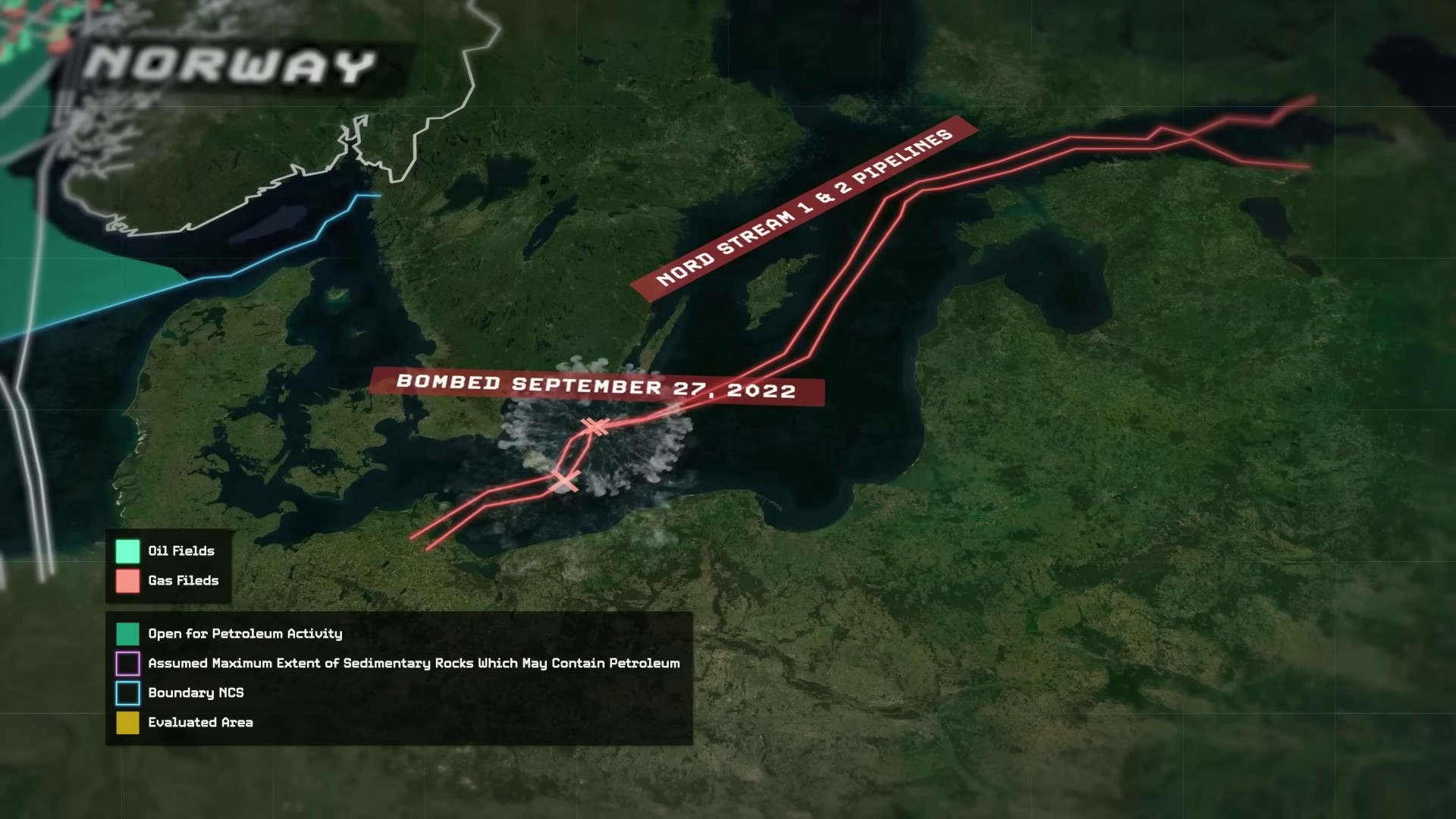

Hence, prior to the rise of liquefied natural gas production, gas markets were highly regional due to geographical constraints. This resulted in Europe building an extensive pipeline system to transport natural gas from relatively nearby sources to consumers. The largest of these, in the 20th and early 21st centuries, were developed from the relatively proximate gas sources in the Netherlands, Algeria, Soviet and later Russian Siberian fields, Azerbaijan after the Soviet Union's collapse, and of course, Norway and the Norwegian continental shelf. This historical precedent made the EU largely dependent on natural gas imports from its three closest and largest neighbors - Russia, Norway, and Algeria.

Norway built a total of 11 sub-sea gas pipelines that directly connected their gas resources to European consumers. In 2010, Norwegian gas production surpassed the country's oil production for the first time due to growing demand in the EU and UK. By the 2010s, Norway had already emerged as the second-largest exporter of natural gas to the EU, second only to Russia. In 2021, before Russia launched its full-scale invasion into Ukraine, Russia was supplying about 40% of the EU's total gas imports, compared to Norway's 25%, and Russia also provided 25% of the EU's oil imports, compared to Norway's 9.4%. By then, with billions of dollars pouring into Norway annually, it had essentially become a petrostate - the only one in Europe outside Russia. In 2021, oil and gas accounted for approximately 21% of Norway's entire GDP, and an astounding 51% of all their exports by value. However, unlike many other petrostates, Norway has successfully avoided falling into stereotypes of corruption and authoritarianism thanks to several distinctive factors.

While there's no universally accepted definition for a petrostate, the term usually refers to countries heavily reliant on oil and gas extraction and exports to the point where their economies could collapse without these industries. In this context, 25 countries across South America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia are typically considered to be the classic examples of petrostates.

Out of these 25, every one of them is deemed by the Economist Democracy Index to be either authoritarian or hybrid regimes, except for two - Indonesia and Norway. However, Norway outshines all of them, including Indonesia, because it is ranked by the same index as being the most democratic, free, and equal society globally. This puts its status as a petrostate in stark contrast to countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, and Venezuela, which are among the world's most heavily authoritarian and corrupt nations.

The major reason why the influx of oil and gas resources didn't transform Norway into a typically authoritarian and corrupt petrostate like many of its counterparts is due to the country's unique geography, history, and strategic government policies.

Norway's discovery of oil was unique because of its long-established tradition of communal resource ownership, wealth equitability, industrialization, and democracy. On the other hand, countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, and Venezuela uncovered oil while under autocratic regimes, leading to consolidated power and wealth. The oil industries in Syria, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and across Africa were transitioned from European colonial administrations to autocratic dictatorships.

Norway, a stable democracy with low inequality, managed its oil wealth more effectively. However, the oil-dependent Norwegian economy encountered a recession in 1986 when oil prices crashed after a period of rapid growth in the 1970s and early '80s.

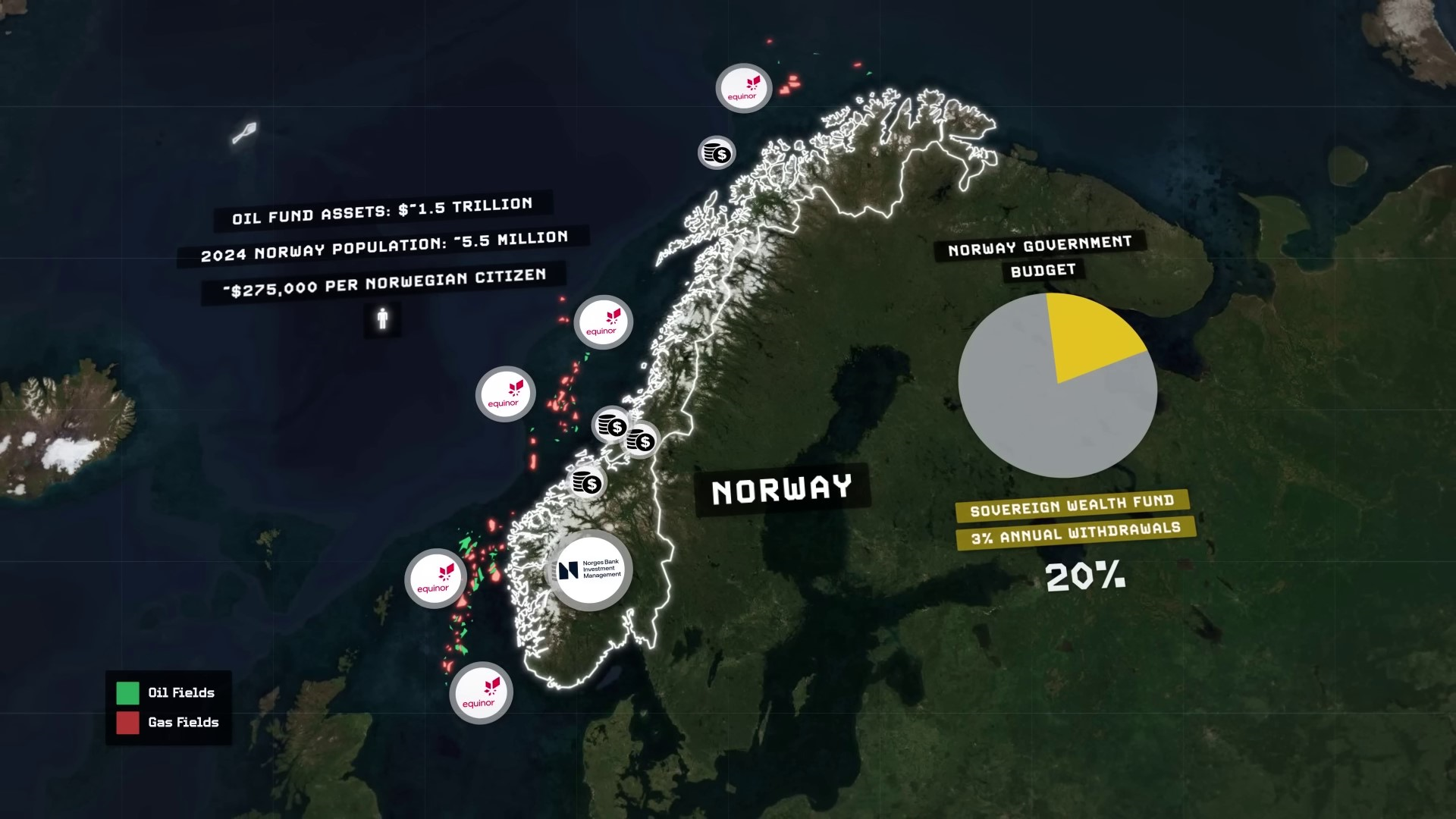

There have only been three occasions when the Norwegian economy has shrunk: in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2009 during the Financial Crisis, and in 1988 during an oil recession. The Norwegian government learned from the 1980s recession and realised the need to diversify away from the oil market. This led to the establishment of the Pension Fund Global in 1990. This sovereign wealth fund, which is financed by surplus revenues from Equinor and taxes on the oil industry, invests in worldwide markets and real estate. Strict rules limit withdrawals to 3% per year to ensure steady growth and prevent misuse by politicians. Since its inception, the fund has grown substantially and has become a valuable asset for Norway's future generations.

Norway's Sovereign Wealth Fund, Energy Approach, and Influence in Europe | 0:26:35-0:38:15

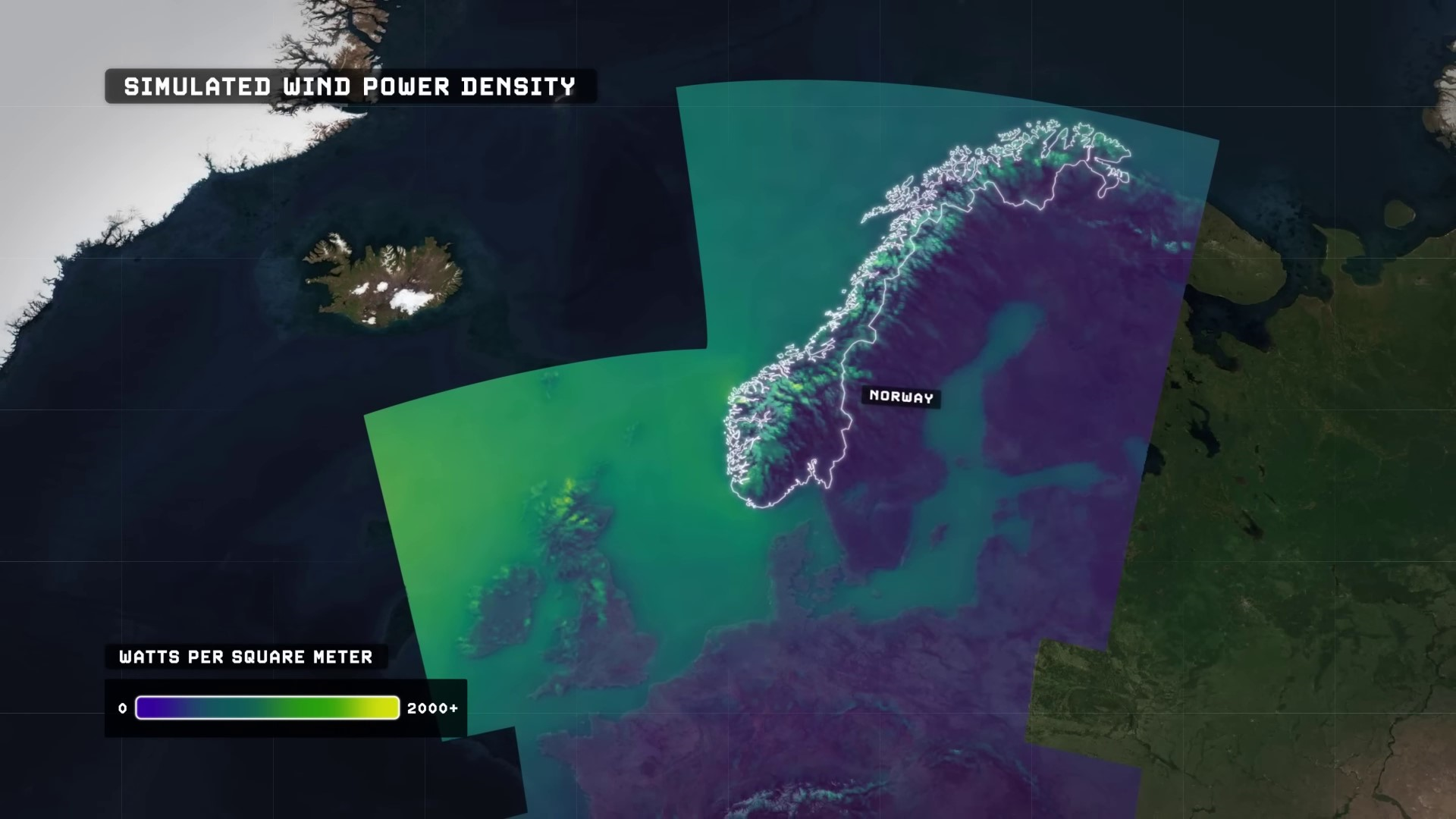

Norway's sovereign wealth fund is the largest in the world, boasting over 1.5 trillion US dollars in net assets, and owns 1.5% of all publicly traded companies globally. Despite Norway's small economy and population, the fund is worth $275,000 per citizen. The fund's 3% withdrawal rate can cover 20% of the government's annual budget. Norway is a significant oil and gas producer and exporter, ranking 13th in oil production and 9th in gas production. The country's renewable energy sources, including hydropower and wind, contribute to its energy self-sufficiency.

Norway also has the 18th largest installed wind capacity in the world and has massive untapped potential in this area that is just beginning to grow. Besides having large amounts of oil and gas, the country has huge potential for renewable energy, and they've been using that potential strategically. They effectively keep all of their renewable hydro and wind resources in-house to indefinitely meet their own energy demands, which frees them up to sell most of their oil and gas resources to countries abroad, particularly to the energy-hungry European Union (EU) next door.

In addition to harnessing their local hydro, wind, and even geothermal potential to effectively transition their entire electric grid to 100% domestically-produced renewables, they're also reducing their reliance on fossil fuels by offering generous tax and financial incentives to citizens who adopt fully electric vehicles (EVs). As a result, 88% of all new car sales in Norway in 2022 were EVs. This is the highest market share that EVs have yet achieved in any country. With the pro-EV policies in place for a long time, nearly one in every three vehicles on Norway's roads are already EVs that do not consume oil and are powered by the state's domestic renewable energy sources.

For Norway, this is about more than just reducing emissions and combating climate change. The country also sees it as a matter of national security and financial power. As Norway becomes more reliant on its homegrown, renewable sources for electricity, the country becomes less dependent on foreign energy imports and supply chains. Conversely, the more oil and gas resources Norway can sell abroad, the more money it can invest in its sovereign wealth fund to diversify its economy and decrease its dependence on oil. Adopting more EVs that can be powered by domestic renewable sources means they can sell even more of their oil resources abroad. This cascading strategy, pursued by Norway for decades, has been transforming the country into one of the most powerful and influential states in Europe.

Norway's unique philosophy for the 21st century is to produce and sell its oil and gas resources abroad while harnessing and providing its renewable resources for its own people. This clever strategy has set them up to export all of the oil and gas they produce while also being completely energy independent. This strategy has driven Norway's modest global oil and gas reserves and production levels to make up a significant amount of the world's total exports, greatly increasing the wealth of the nation.

This prudence and decades of forward-thinking strategic planning paid off in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. The EU decided to cut off their massive imports of Russian oil and gas to deny the Kremlin a primary source of funding for their war effort. With its large oil and gas resources and friendly relations, Norway was well positioned to fulfill the demand. Subsequently, exports of Norwegian oil by tankers and gas through pipelines saw an increase.

The surge in exports to the EU market to replace Russian supplies led to a financial windfall for Norway's oil and gas industry. Revenue from oil and gas reached $131 billion in 2023, a significant increase from previous years. This income has been invested in the Sovereign Wealth Fund and the exploration of untapped oil and gas deposits in the Barents Sea. Infrastructure, such as pipelines to Europe, has been expanded to increase export capacity and to replace Russian market share.

The culmination of Norway's growing influence in the European energy market was seen in September 2022. A series of underwater bombings destroyed sections of the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines, cutting off Germany's direct supply of gas from Russia's Siberian fields. The day after the bombings, Norway and Poland inaugurated the Baltic Pipe, Norway's new gas pipeline to Poland, replacing 60% of Poland's natural gas imports previously sourced from Russia.

Norway has therefore emerged as the EU's largest single energy supplier in the 2020s, and it's likely to extend beyond just oil and gas in the future. As climate change progresses, precipitation levels in Norway are expected to increase, feeding more water into the rivers leading to the seas and coastal areas. In addition, Norway's largely untapped wind potential is expected to be exploited, making the country a global leader in wind energy.

Norway's wealth of rare earth minerals is also well known, and a global push towards green energy transition, spearheaded by many European economies, is expected to demand these resources greatly. Currently, China dominates the world's rare earth reserves, and controls 63% of all global rare earth mining. Norway has the potential to help diversify this resource and weaken China's hold over the rare earth market. This is yet another way in which the country is well-positioned for the growing energy needs of the future.

China's New Export Restrictions on Ore | 0:38:15-0:38:35

In July 2023, China announced new export restrictions on gallium and germanium, essential metals for semiconductor manufacturing, in response to US sanctions on China's semiconductor industry. China is a major producer of gallium and germanium, with 98% and 68% of global production, respectively. The restrictions could impact global semiconductor supply chains and technology industries.

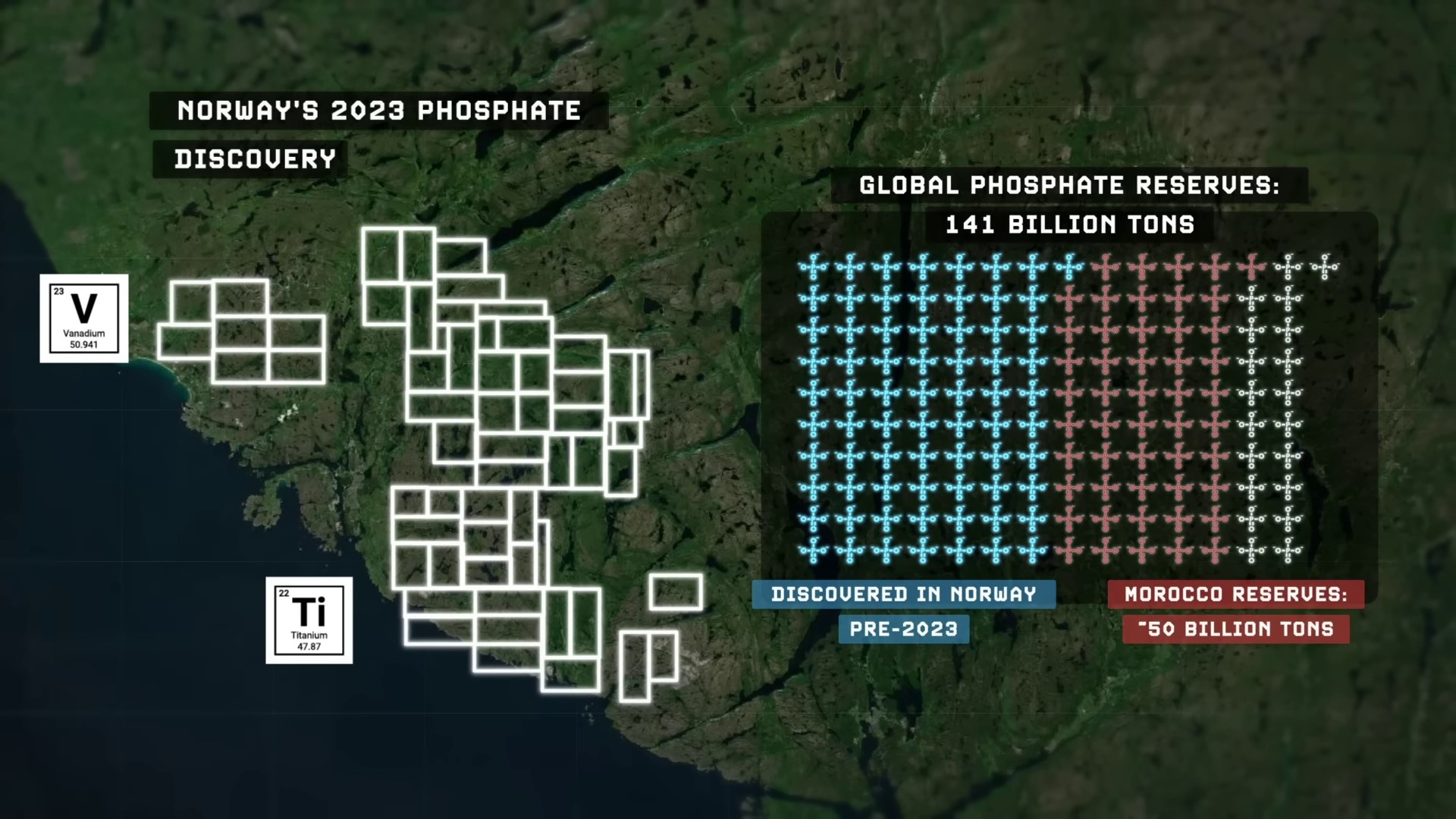

In June 2023, Norge Mining in Norway discovered the largest reserve of phosphate rock in the world, containing around 70 billion tons. This discovery doubled the world's previous proven reserves of phosphate. The phosphate deposit in southern Norway also contains metals like titanium and vanadium, crucial for various industries. China's dominance in the production of these metals has led to geopolitical tensions and reliance on tenuous supply chains for the US and EU. The discovery in Norway has the potential to shift the global market dynamics for these critical resources.

Norway's potential as a major source of titanium, vanadium, phosphates, oil, and gas could lead to increased strategic autonomy for Europe and the West. By relying on democratic countries for raw materials instead of autocratic providers, Norway is poised for continued economic growth and prosperity. The country's focus on expanding its sovereign wealth fund, renewable energy, and electrification efforts positions it for long-term success. The ability to visualize and understand this data on a map enhances the fascination of learning about geopolitics. The sponsor of the video mentioned, Brilliant, offers a STEM learning platform that encourages active learning and flexibility for busy schedules.