Why the Panama Canal is Dying — RealLifeLore

RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Significance of the Panama Canal | 0:00:00-0:03:40

- Challenges in Traffic through the Panama Canal | 0:03:40-0:06:40

- Panama’s Weather Patterns Disrupted by El Niño Event in 2023 | 0:06:40-0:10:00

- Panama’s Dilemma: Water Allocation for Panama Canal vs. Citizens | 0:10:00-0:13:40

- Japanese Merchant Vessel Pays Record Bid to Skip Panama Canal Line | 0:13:40-0:16:10

- Proposed Alternative to the Panama Canal: The Bi-Oceanic Corridor | 0:16:10-0:22:30

- Colombia’s Interoceanic Train Network Project | 0:22:30-0:25:20

- HKND’s Failed Nicaragua Canal Project | 0:25:20-0:29:00

- Mexico’s Inner Oceanic Corridor | 0:29:00-0:30:30

- The Importance of Preparation for Panama’s Future | 0:33:00-

Significance of the Panama Canal | 0:00:00-0:03:40

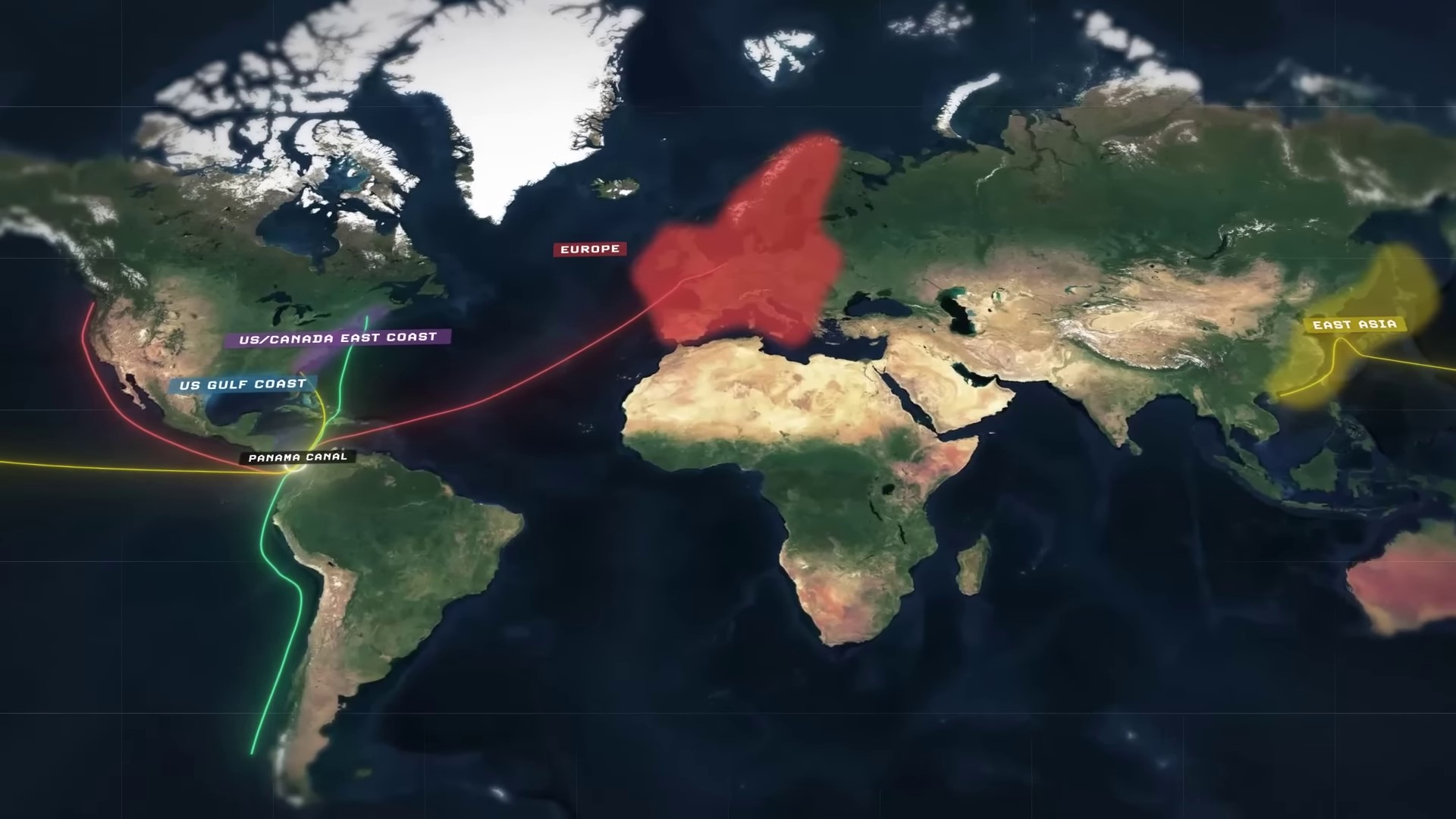

The Panama Canal is the most significant maritime chokepoint in the Western Hemisphere, providing a crucial shortcut for ships traveling between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. It serves as a primary trade route for merchant vessels transporting goods between various regions, including the U.S. East Coast, East Asia, Europe, and South America. The canal’s strategic importance is highlighted by its role in facilitating rapid redeployment of naval assets for the United States. While previously owned by the U.S., control was handed over to Panama in 2000. The canal continues to be of vital interest to the U.S., particularly in potential conflicts with China over Taiwan. Its economic impact is substantial, generating billions for Panama’s government and playing a central role in the country’s economy.

The Panama Canal is a crucial route for the country’s development and the global economy. Its breakdown in 2023 and 2024 has raised concerns about its future and the impact on international trade. Unlike the Suez Canal, which is disrupted by a war, the Panama Canal’s issues are internal and pose a threat to the country’s stability and the global economy.

Challenges in Traffic through the Panama Canal | 0:03:40-0:06:40

The disruption in traffic through the Panama Canal is primarily due to natural and geographic challenges such as unpredictable climate change, increased droughts, and competition from rival alternatives. The unique operation of the Panama Canal involves a series of locks that raise and lower water levels to allow ships to pass through. The war in the Middle East is expected to end, leading to a return of traffic through the Suez Canal, potentially reducing traffic through the Panama Canal indefinitely.

The ship passes through the second gate into the second lock, the gates are closed, and the water level is adjusted between the second and third locks. The water level is raised back up again from the lake on the other side, then the third gate opens up, the ship travels into the third lock, and then, just like that, the ship has been raised up 26 meters in elevation above from where it started at sea level, and can then effortlessly travel the rest of the way across Panama largely over Lake Gatun at 26 meters up in elevation, which was a lake that was artificially created by damming the nearby Chagras River to enters that first lock.

The water level within the lock is raised by the water being pumped into it from the second lock, which originally came down the chain from Lake Atun itself. But then, in order to accept the next ship into the canal from sea level, that extra water in the first lock has to be emptied out into the ocean, and this is the same on either of the canal’s ends. The water that the canal uses for this whole process comes from the two artificially created freshwater reservoirs nearby, Lake Alajuela and Lake Gatun, with Lake Gatun being by far the primary source. Each transit through the Panama Canal consumes around 52 million gallons of freshwater from these reservoirs to make the whole process possible, and then the water that’s lost from the reservoirs is usually replenished with rainfall. So, the canal relies on rain to replenish the lakes, which in turn provides water for the canal to operate and deliver economic and strategic benefits. However, during a severe drought in 2023, the system began to break down due to insufficient rainfall to replenish the lakes.

Panama’s Weather Patterns Disrupted by El Niño Event in 2023 | 0:06:40-0:10:00

Panama experiences distinct wet and dry seasons throughout the year, with the wet season typically lasting from April to November and the dry season from December to March. In 2023, an El Niño event disrupts this pattern by weakening the trade winds in the central and east central Pacific Ocean. This phenomenon causes warm water to be pushed back towards the east, impacting Panama’s usual weather patterns.

Back towards the Americas west coast, it prevents deeper, colder waters from upwelling towards the surface. This creates a big patch of warm water that sits off the west coast and disrupts the area’s usual atmospheric circulation pattern, i.e., the winds that usually carry rains, since record-keeping began back in the 1950s.

October is usually the rainiest month of the year for the country. Overall, the 2023 rainy season in Panama ultimately failed to materialize, with the government reporting that the year saw the second lowest levels of rainfall ever measured in Panama’s history, and built more than 100 years ago now back in the early 20th century before modern climate change and climatic effects were well understood. The Panama Canal was never originally designed with this severe of a reduction in rainfall in the future ever being in mind. Without the rains replenishing the lakes, and with the canal still consuming huge amounts of the water from the lakes to continue operating, the lakes’ water levels have been decreasing to unprecedentedly dangerous levels, down to about 3 meters lower than they usually are at this time of year. And now in January going into February, Panama is in the middle of its usual dry season and the lakes aren’t expected to begin getting any of their replenishing waters until the next wet season starts to hopefully pick back up again in April.

El Nino events typically last for around 9 to 12 months, but due to worsening effects of climate change, they can sometimes last longer, even for years. In September 2023, Noah predicted a 60% chance of the ongoing El Nino lasting through summer 2024. This could impact the rainy season in Panama and the canal’s water source.

Panama’s Dilemma: Water Allocation for Panama Canal vs. Citizens | 0:10:00-0:13:40

Panama is facing a difficult decision regarding the allocation of diminishing water supplies from the lake. The Panama Canal, which funds the government with billions of dollars and represents 6.5% of the country’s GDP, requires a significant amount of water for operation. However, millions of Panamanian citizens depend on the same water supply for drinking water. The government is left with the choice of either rationing water supplies for the canal or for its people.

And so far, the government has been choosing to ration the water supplies for the canal, by enforcing a series of increasingly harsh restrictions on the canal’s usage. The Panama Canal Authority that oversees the canal’s operation has been steadily adapting to the changing circumstances by reducing the number of ships that are allowed to pass through, usually under normal circumstances. A total of 36 ships are allowed to pass through the canal on a daily basis, but as the water crisis in the country has intensified, the limit has been steadily getting reduced. Down to 31 ships per day, and then down to 24 ships per day, and in February, the limit is expected to decrease even further, down to only 18 ships per day, usually reduce the amount of water that they need to pump into the locks to keep the ships afloat in them.

The authorities are also restricting the volumes of cargo the ships are allowed to carry with them through the canal. With lighter loads, the ships displace less water and require less water to move through the locks. But it also means that in addition to only half of the ships as usual being allowed to pass through the canal, the fewer ships that even are being allowed to pass through or carrying up to 40% less cargo than they usually would be. Combined, these series of restrictions on trade through the Panama Canal have been generating massive delays for ships wanting to pass through it, which is causing huge disruptions in the trade flows between the US and Canadian East Coast and Asia, between the US and Canadian West Coast with Europe, and between the US East Coast the South American West Coast.

Before the restrictions, ships who wanted to pass through the Panama Canal could either book their passage up to three weeks in advance or simply show up without a reservation and wait in line. As recently as the beginning of November 2023, the average wait time for these ships showing up without a reservation was still only around two days, and was still far better than taking the alternative route around South America that usually adds around 18 extra days of travel. But within only a month by the end of November, as the Panama Canal Authority began enforcing its heavier restrictions, these average wait times for ships without reservations skyrocketed by more than 5 times over, to an average of nearly 11 and a half days, with a maximum for some ships traveling south bound from the Atlantic to the Pacific, nearly reaching a whopping 23 days of waiting. Which means that traveling all the way around South America would have actually been quicker in some instances. And while booking reservations in advance to use the canal used to be made three weeks beforehand, they’re now often being made months in advance as the bottleneck continues getting worse. These are the longest wait times that the Panama Canal has ever experienced in its entire history of operation, and videos have captured the more than 120 ships at a time now that have been caught stuck waiting outside for their chance to pass through.

Now, ships arriving at the Panama Canal without a reservation are facing three difficult choices of their own that they have to make. Option one, they arrive and basically pay a bribe to the Panama Canal Authority to skip the line and advance through the canal quickly ahead of everyone else who didn’t pay.

Japanese Merchant Vessel Pays Record Bid to Skip Panama Canal Line | 0:13:40-0:16:10

In November 2023, a Japanese merchant vessel paid a record bid of nearly $4 million to skip the line at the Panama Canal. However, bids to skip the line have decreased to an average of $269,000 by January 2024 as more ships opt to avoid the canal entirely due to limited alternative routes.

The ongoing crisis at the Suez Canal, with Iranian-backed Houthis attacking ships, has led to most shipping companies avoiding the area. This has forced container ships to take longer and more expensive routes around South America or Africa. The situation poses challenges for shipping companies, leading to increased costs and inflationary pressures that impact global economies. Unlike the crisis in the Red Sea, which involves military intervention, the Panama Canal issue can only be resolved by waiting for the situation to improve, or by spending years and a lot of money building out new infrastructure projects to make sure that a situation like this doesn’t happen again in the future

Proposed Alternative to the Panama Canal: The Bi-Oceanic Corridor | 0:16:10-0:22:30

The substantial logistical bottleneck at the Panama Canal, compounded by the growing unpredictability of climate change, may persistently generate similar issues in the future, prompting renewed interest in proposed alternatives to the canal. Historically, these proposals haven’t really ever gone anywhere while the Panama Canal has functioned normally. But these proposals could all of a sudden, now, completely revolutionize the way that the trade flows around the world in the near future, which could end up deeply cutting into the increasingly unreliable Panama Canal’s market share. As it currently stands, there are four major infrastructure projects that have been proposed across the Americas as alternatives to the Panama Canal in the 21st century with varying levels of credibility and non-credibility.

The first major proposed alternative has been the so-called bi-oceanic corridor, a series of paved highways and bridges extending across lower South America through the countries of Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil that will eventually enable trucks to carry goods from coast to coast rather than ships. Nothing quite like this has ever been built before in the region because of South America’s uniquely challenging geography. The continent beneath the Panama Canal has always presented challenging barriers to regional integration. It is a continent that is dominated in the west by the enormous Andes mountain chain, the longest continuous mountain chain anywhere on the surface of the earth that runs for nearly 9,000 kilometers and the highest mountain chain located anywhere outside of Asia, with average elevations of more than 4,000 meters above sea level. The Andes effectively block the entirety of South America’s west coast from being able to access the continental interior, while the infamously dense jungles of the Amazon rainforest effectively block off the entirety of South America’s northern coast from being able to access the continental continental interior as well.

These geographic facts meant that over a period of centuries as European colonization of the continent accelerated, three distinctly separated areas of civilization and high population density arose in South America that exist today. The east coast of the continent in Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, the southwest coast in Chile, and the northwest coast in an arc running from Bolivia through Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. The existence of the Andes Mountains and the Amazon Rainforest has long prevented the construction of land-based train links like roads or railways between all three of these centers of population.

Trade between South American regions has historically been maritime-based despite being technically connected by land. Most maritime trade in the 20th century went through the Panama Canal. Some countries in South America still lack roads connecting them, such as Colombia to Panama, Brazil, or Peru, Venezuela to Guyana, and Suriname to Brazil. The first road connecting Brazil and Peru was completed in 2011, and as of 2019, a large region in western Paraguay the size of Austria had no paved roads.

The first road connecting Brazil and Peru was completed in 2011, and as of 2019, a large region in western Paraguay the size of Austria had no paved roads. This region in Paraguay is part of the overall Gran Chaco region of South America, a huge, hot, and arid sprawl of scrubland, savannah, and swamps that extends east of the Andes Mountains across Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil as well. With very little freshwater resources and very little rainfall trapped in the rain shadow of the Andes Mountains to the west, the Grand Chaco has always been an underdeveloped part of the South American. It takes up two-thirds of all of Paraguay’s territory and yet it is only home to 3% of Paraguay’s population. Which is why an area the size of Austria here didn’t have any paved roads as recently as 2019.

But now only a few years later, Paraguay has gone on an unprecedented highway building spree running throughout the area. 3,000 kilometers worth of additional roads and bridges have been paved in the country since then. And by next year in 2025, their long-talked-about biocentric corridor should finally be completed, and once it is, Paraguay argues that it will stand as the linchpin in one of the world’s most significant new trade routes that will compete directly with the Panama Canal for business. The so-called Southern Cone region of South America is overall the continent’s most prosperous and most economically productive. Its latitude, mirrored in the Northern Hemisphere, would roughly correspond to the latitudes of the US mainland, Europe, Northern China, Korea, and Japan. Once the Biotianic Corridor is open and fully operational soon, trucks from South in More importantly, the Biotianic Corridor will prove revolutionary for the development of the so-called Lithium Triangle region located nearby to it right here.

Across Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina lies a region believed to hold over half of the world’s known reserves of lithium, a crucial element for various industries. Trucks transport lithium from this area to Atlantic ports in Argentina and Brazil for direct export to the US East Coast and Europe, bypassing the Panama Canal entirely.

This strategic positioning could potentially elevate Paraguay as a key player in the future’s green energy trade if it plays its cards right. Moreover, it could establish the Bi-oceanic Corridor as one of the most significant trade routes globally, necessitating secure and stable management.

Paraguay asserts that upon completion, the project will save Southern Cone countries 14 days of travel time and a thousand dollars per container compared to using the Panama Canal. If validated, this would represent a substantial reduction in current logistics costs, likely encroaching on the Panama Canal’s market share.

Colombia’s Interoceanic Train Network Project | 0:22:30-0:25:20

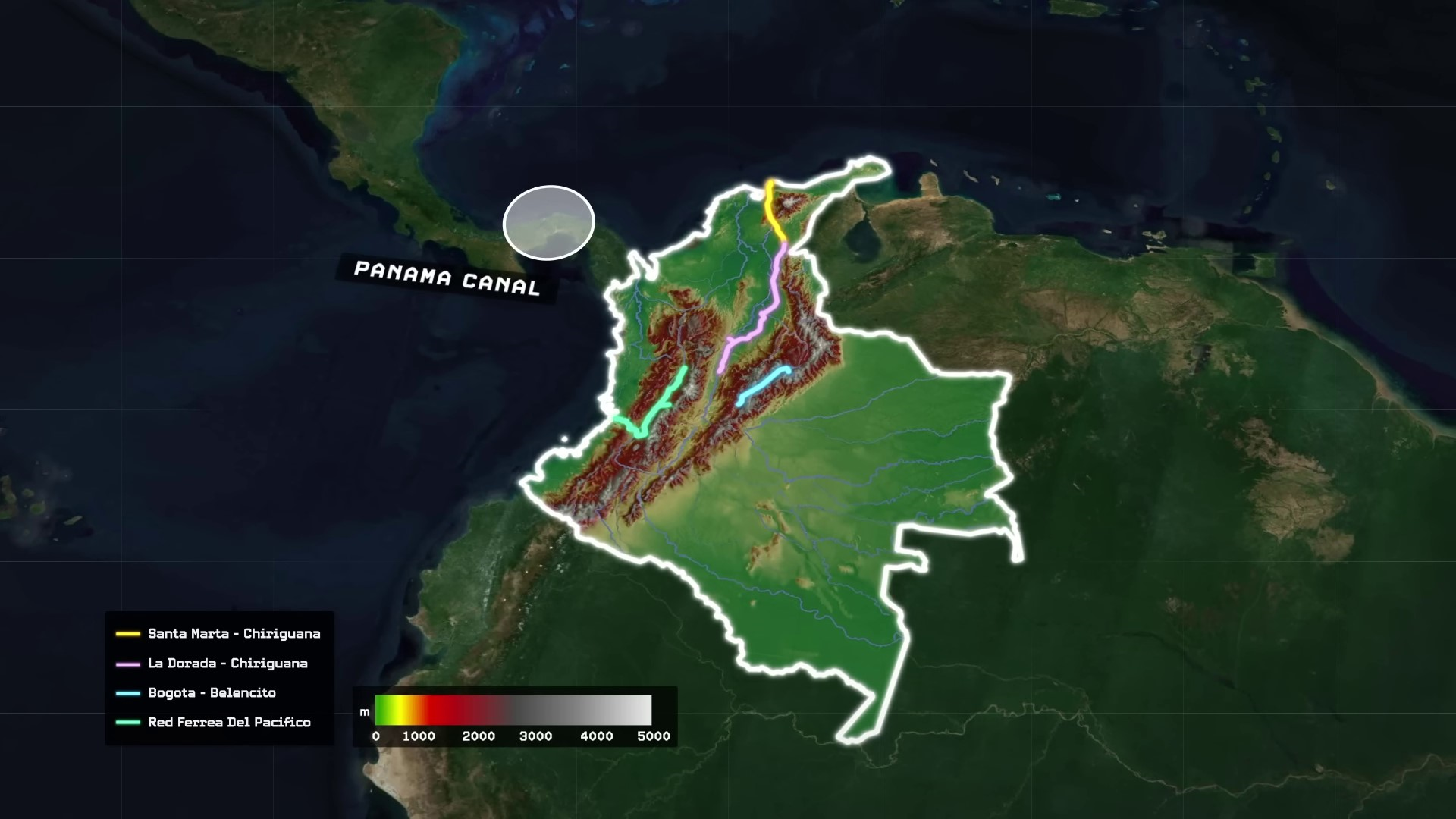

A second proposed alternative to the Panama Canal lies further north in South America, spanning across Colombia. Colombia currently hosts four distinct freight railway networks: two in the east connecting to the Caribbean coast, one in the west linking to the Pacific coast, and an additional network in the east with no coast connections.

Colombia plans to build an interoceanic train network through the Andes Mountains to connect the country’s railways between the Pacific and the Caribbean. The project involves building nearly 200 kilometers of track, including tunnels, to transform Colombia into a global trade hub. In contrast, Nicaragua has a long-standing proposal to build a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Lake Nicaragua. The project was revived in 2012, with the Nicaraguan government authorizing the creation of a state-owned Nicaragua Canal Authority and awarding the construction bid to a Chinese company in 2013.

HKND’s Failed Nicaragua Canal Project | 0:25:20-0:29:00

HKND, led by Chinese billionaire Wang Jing, planned to construct the Nicaragua Canal with $50 billion in funding. The project aimed to rival the Panama Canal and double Nicaragua’s GDP. However, environmental concerns and financial setbacks led to its failure. Wang Jing’s fortune declined drastically, and construction never began. Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega faces criticism for his authoritarian rule and unfair elections, leading to mass exodus and strained relations with the US. Nicaragua remains one of the poorest and most corrupt countries in the Americas.

Nicaragua ranks as one of the worst countries riddled by corruption in the Americas on the Corruption Perception Index, an annual index compiled by Transparency International based in Germany. Nicaragua is ranked as the 11th most corrupt country in the world in 2022, following countries like North Korea, Haiti, Yemen, and Venezuela. The possibility of Nicaragua creating a canal costing tens of billions of dollars seems bleak. As an alternative to the Panama Canal, there have been proposals to create a canal in Mexico’s narrow isthmus of Tehuantepec, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. This idea has been considered for centuries since Hernán Cortés first encountered the region.

Mexico’s Inner Oceanic Corridor | 0:29:00-0:30:30

The Isthmus, at its narrowest point, separates the two oceans by about 192 kilometers, similar in length to the Suez Canal. In 1907, the Mexican government built a railway across the Isthmus for freight transport, but the Mexican Revolution in 1910 led to chaos. The Panama Canal opened in 1914, impacting the Tehuantepec Railway. By 2020, under President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the Mexican government took action regarding the railway.

Mexico, under President AMLO, is revitalizing the Tehuantepec rail route to create the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The project includes modernizing ports, building a high-capacity rail line, and constructing industrial parks. The government is investing $2.85 billion, aiming for completion in the early 2030s. The corridor is expected to be a faster and cheaper alternative to the Panama Canal, capable of carrying 300,000 cargo containers annually by 2028.

By 2033, Mexico’s inner oceanic corridor of the Tehuantepec is projected to move about half the volume of the Panama Canal. This project is crucial for developing Mexico’s south and is considered the most important infrastructure project under AMLO’s administration. The Panama Canal Authority faces potential competition from alternative projects in Mexico, Nicaragua, Colombia, and Paraguay. To address challenges, the Panama Canal Authority is considering solutions like damming up the Indio River and upgrading the canal at an estimated cost of $900 million over 6 years. Climate change poses a threat to the Panama Canal’s reliability, prompting the need for adaptation to prevent losing market share to emerging competitors.

The Importance of Preparation for Panama’s Future | 0:33:00-

In order to safeguard their own future and continued prosperity, Panama must begin preparing now by taking difficult decisions, lest they wake up one day and realize that the flow of global trade has suddenly circumvented them. Panama has been at the epicenter of globalized trade in the Western Hemisphere for more than a century now, but it cannot afford to be comfortable or complacent, because this may not remain the same case for the next century.