Why Venezuela is Preparing to Conquer Guyana — @RealLifeLore

@RealLifeLore Infographic Summary

Table of Contents

- Venezuela’s Controversial Annexation of Essequibo Region | 0:00:00-0:01:40

- Population and Infrastructure in the Essequibo Region | 0:01:40-0:03:40

- The Complex Situation Surrounding Oil in Guyana and Venezuela | 0:03:40-0:10:20

- Continuous Decline in Venezuela’s Oil Production | 0:10:20-0:15:20

- History of Venezuela’s Oil Economy | 0:15:20-0:23:40

- Venezuela’s Current Situation | 0:23:40-0:30:00

- Venezuela’s Territorial Claim and Implications for the United States | 0:30:00-0:37:20

- Maduro’s Strategic Moves in 2023–2024 | 0:37:20-0:43:40

https://youtu.be/DQ7fTSirNDs

Venezuela’s Controversial Annexation of Essequibo Region | 0:00:00-0:01:40

The Venezuelan government claimed that 95% of the votes in favor of annexing the Essequibo region from Guyana were in favor of the annexation. This would result in the creation of a new Venezuelan state to be called Guyana-Essequibo. In reality, third-party international observers believe that fewer than 2.4 million Venezuelans actually participated in the referendum. But that didn’t stop Venezuela’s decade-long autocratic leader, Nicolas Maduro, from declaring that the Venezuelan people had spoken loud and clear, claiming that the vote was so overwhelming that the Venezuelan government had no other choice than to abide by it. Maduro immediately ordered the publishing of a brand new official map of Venezuela that includes the Essequibo territory to be displayed in every school, university, government building, and house in the country. A Venezuelan general was immediately appointed by Maduro to become Venezuela’s new governor of the territory, while Venezuelan troop movements directly near the border with Essequibo began increasing in activity. The Venezuelan government promptly issued arrest warrants for political candidates in the country who opposed the referendum and the annexation. Well, immediately before the referendum on the annexation took place, Venezuela’s defense minister very publicly and ominously stated that Venezuela’s dispute with Guyana over the Essequibo is, quote, “not a war for now.” Annexing Essequibo will not be an easy task. The theater of operations will be huge across an area roughly the size of Florida, and at the northern edge of the Amazon rainforest, it’s also almost entirely covered by incredibly dense jungle.

Population and Infrastructure in the Essequibo Region | 0:01:40-0:03:40

The region is also very sparsely populated, with only about a hundred and twenty-eight thousand people actually living there, making the Essequibo one of the most sparsely populated areas. It is so densely jungled and sparsely populated that there has been very little need to build out any infrastructure in the region or develop it from Guyana’s perspective. As a result, there is literally only one single paved road that runs from Venezuela into the Essequibo region and into Guyana in general, and it runs through Brazil first before entering Guyana later.

Immediately alarmed following Venezuela’s referendum and demands for the annexation of Essequibo, and worried that Venezuelan troops and their logistics may use the strategically vital paved road to enforce their claims by marching through their territory, Brazil has already deployed its own troops and vehicles to the region around the road to discourage the Venezuelans from attempting it. At the same time, the United States Air Force has already begun conducting aerial patrols over Guyana’s territory to send a further message to the Venezuelans not to try their luck.

There is a major geopolitical crisis in South America with a risk of state-on-state warfare involving Venezuela, Guyana, Brazil, and the United States over the Essequibo region. Despite the region being underdeveloped and challenging for Venezuela to invade, Venezuela is threatening a land grab war due to historical territorial disputes and economic interests. The sudden escalation in tensions has raised concerns about the potential for conflict in Latin America.

The Complex Situation Surrounding Oil in Guyana and Venezuela | 0:03:40-0:10:20

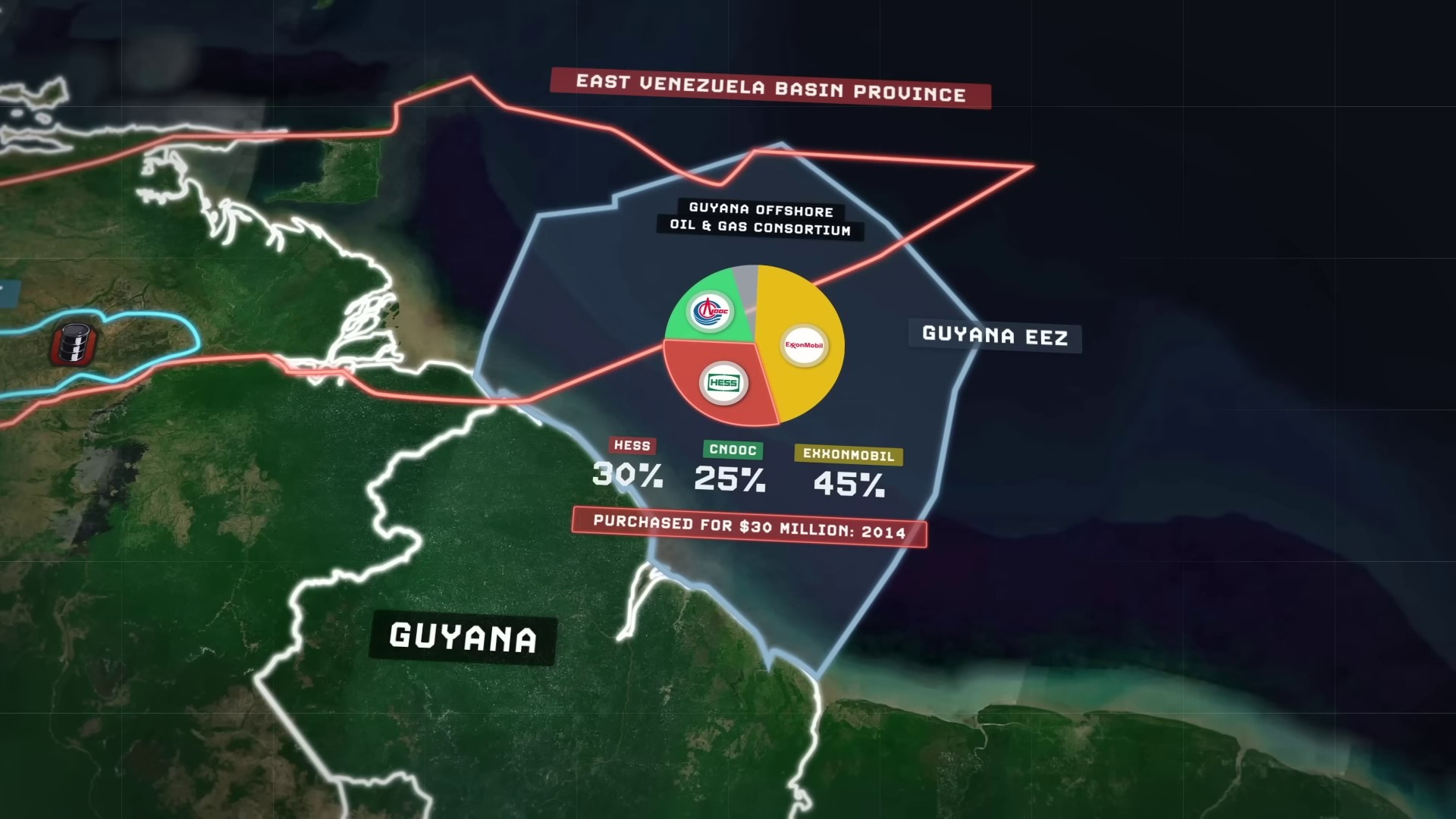

There is a complex geopolitical crisis surrounding oil in Guyana and Venezuela involving global struggles for energy resources, historic grievances, and significant financial stakes. The Orinoco oil belt in Venezuela is a key area with vast crude oil reserves. In 2014, Royal Dutch Shell sold its stake in Guyana’s offshore oil project, which led to significant discoveries by ExxonMobil. In 2015, massive offshore oil deposits in Guyana’s exclusive economic zone were estimated to total around 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil.

This catapulted Guyana to having the 17th largest oil reserves globally. The Exxon-led consortium has invested over $40 billion in offshore oil platforms since 2015, with estimated reserves worth half a trillion dollars by 2023. The consortium splits profits 50–50 with Guyana, with additional royalties. Hess’s stake in the project surged in value, leading to Chevron’s $59 billion buyout. Guyana currently produces 380,000 barrels of oil daily, with potential for further discoveries.

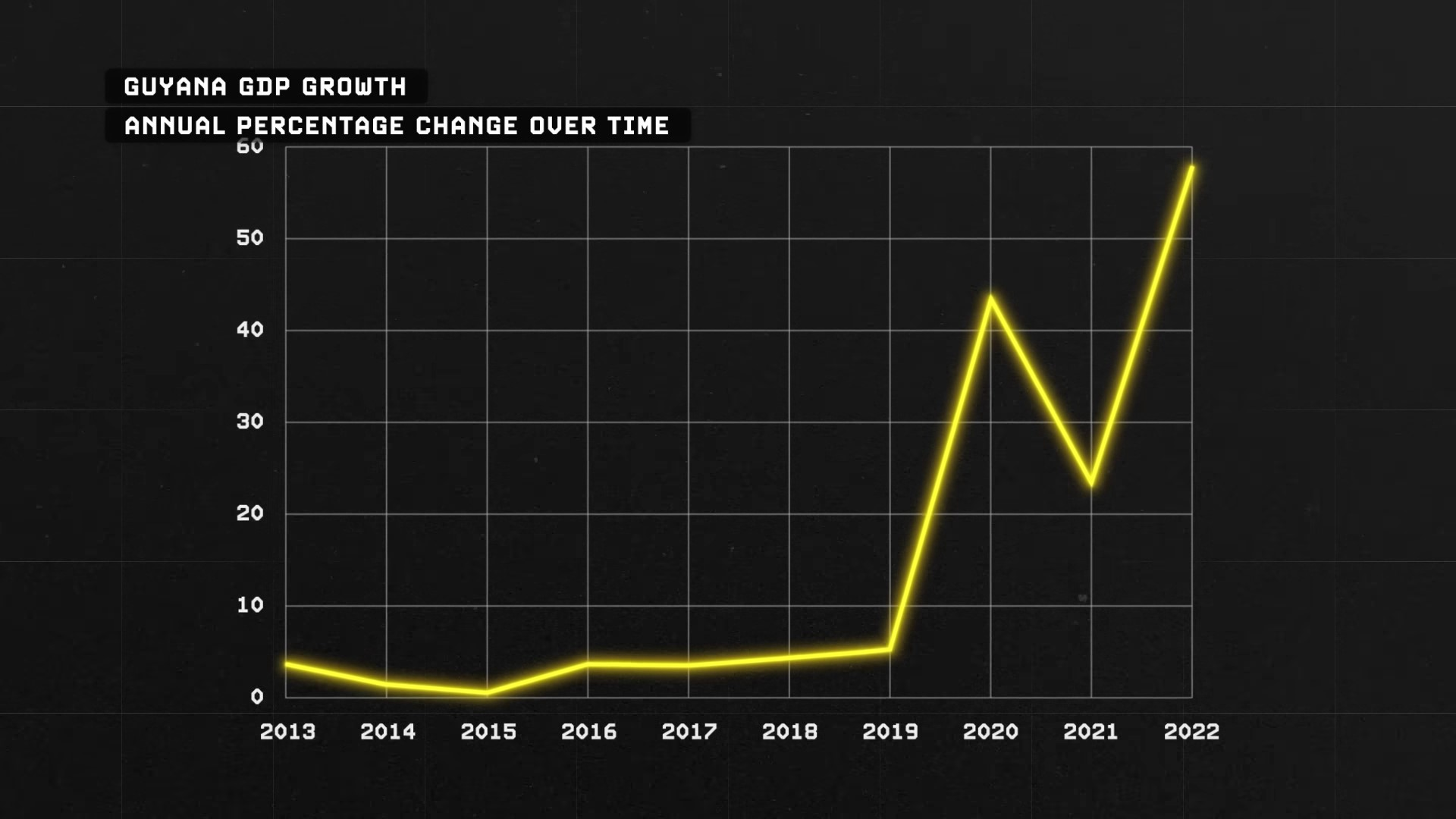

By 2023, or 2028 as more foreign investment pours in and more platforms are developed, they are expected to increase production levels to about 1.2 million barrels per day, which by then will be just over 1% of the entire planet’s production. This would rank Guyana roughly alongside modern-day Algeria’s production levels with a total population of only around 800,000 people. Guyana will by then become, by far, the largest per capita producer of oil in the world, and by 2036, it’s expected that Guyana’s government will be raking in about $16 billion a year in taxes and levies on the oil industry, on an almost unbelievable 62.3% tax. Before the discovery of oil in 2014, Guyana was a sleepy little country with very few other major industries, and so the GDP per capita in the country was nearly $5,400 per person per year, which made it one of the poorest countries in the Americas.

By 2028, with the unexpected oil boom, Guyana’s nominal GDP per capita is expected to rise to more than $37,000 per person within just the next few years, which by then will be the third highest in the Americas only behind the United States and Canada, and about on a par with Italy. It’s for this reason that some people have already taken to calling Guyana the world’s next United Arab Emirates, another small, formerly British-controlled country that was once extremely poor but managed to grow exorbitantly wealthy and influential. Guyana has emerged as a powerful player in the global energy market in the 2020s due to the discovery and harnessing of its oil resources. The country’s oil exports are primarily directed towards the European Union, marking its significance in the energy sector.

Rotterdam in the Netherlands has been benefiting from Guyana’s newly online oil to replace Russian oil due to the war in Ukraine. OPEC has approached Guyana to join the cartel, but Guyana has rejected the offer to maintain independence. Venezuela, with the largest crude oil reserves globally, has struggled to produce oil since the 1990s despite its potential.

Continuous Decline in Venezuela’s Oil Production | 0:10:20-0:15:20

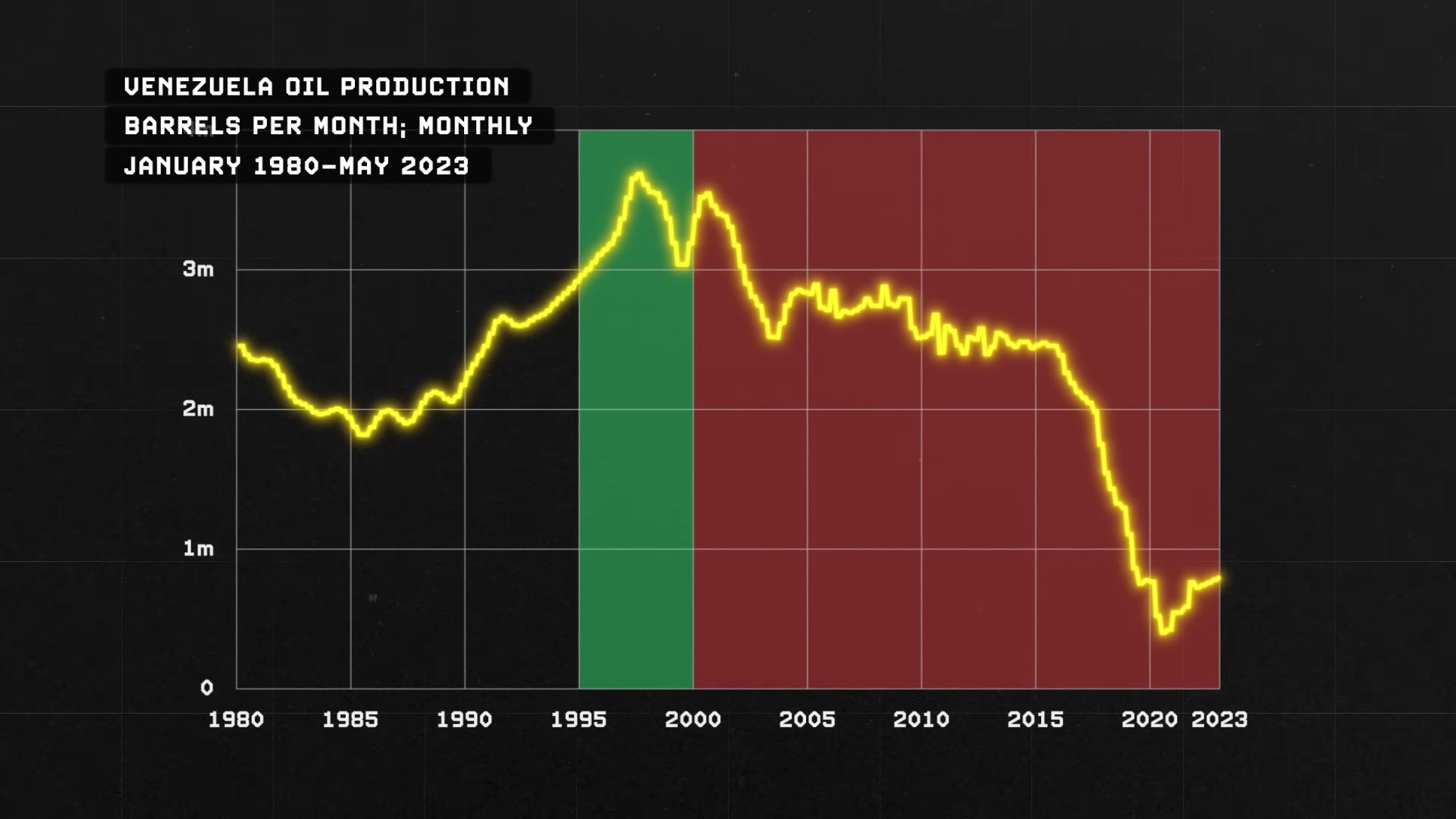

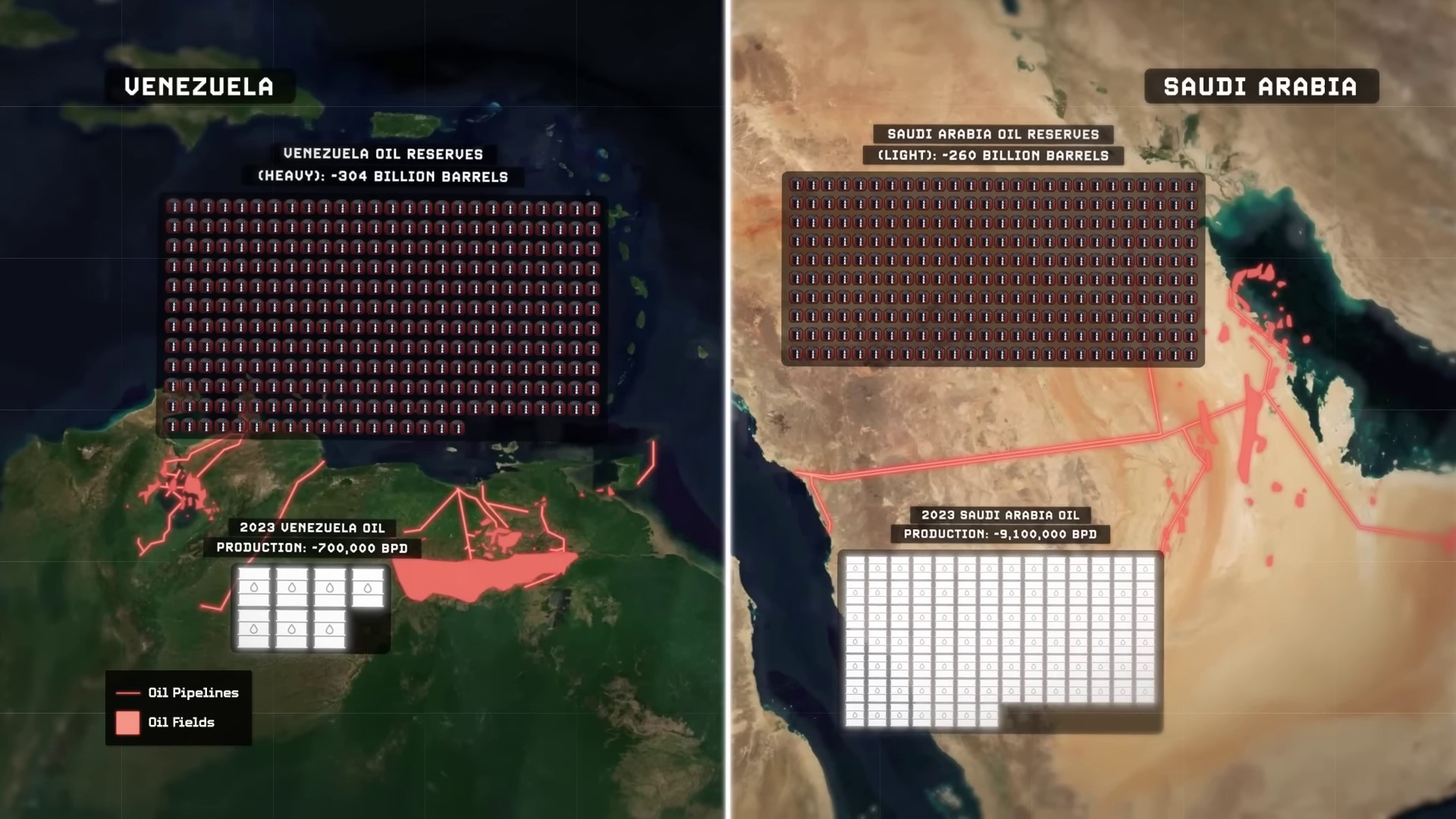

In the mid-1990s, Venezuela’s oil production was around 3.2 million barrels a day, which could have placed them in the top 10 oil producers globally if sustained. But they didn’t maintain that rate, and in fact, they’ve seen a continuous decline in oil production over the past 30 years to the point where today, they’re barely producing more than 700,000 barrels a day, a rate of oil production that’s even less than the United Kingdom, despite Venezuela having more than 120 times the amount of proven reserves as the UK does.

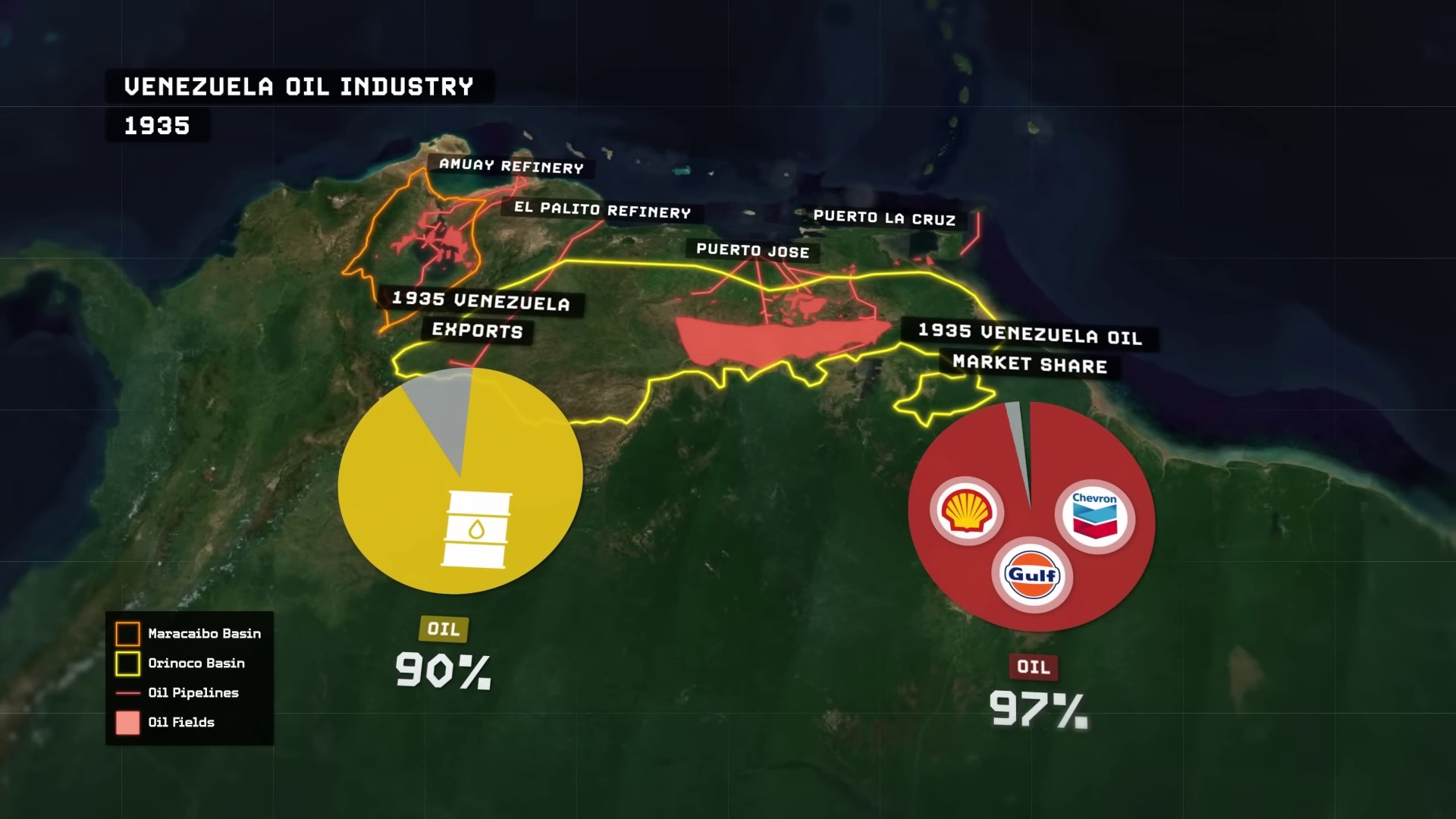

The oil industry in Venezuela dates back more than a century to 1922 when Royal Dutch Shell first hit oil in the country in the Maracaibo Basin here in the far northwest of the country. That discovery sparked an unprecedented oil boom, and by the end of the decade in 1929, there were more than 100 foreign energy companies operating in Venezuela, all drilling for oil. The country’s production had exploded to become the second-highest producer in the entire world, remaining only behind the United States’ oil production itself. But at the same time, Venezuela was ruled by an autocratic military dictatorship, and that regime failed to properly diversify the country’s economy away from the ballooning oil industry. In the first 15 years of when oil was first discovered in the country, oil was already making up more than 90% of all of Venezuela’s exports, and the country had become the leading petrostate in the Western Hemisphere. Moreover, only three foreign energy companies had managed to outmaneuver and outcompete all of the others to dominate 98% of the entire Venezuelan oil market.

In the 1940s, Venezuela passed a new law that required these foreign energy companies to pay half of their oil profits to the state. The companies complied, and Venezuela’s government revenue exploded. But with that came a classic problem that every petro-state before and since has had to confront. With government revenues coming more from taxes on oil production in foreign oil companies, the government begins relying less and less on the taxes from their own citizens. And so, the government begins becoming less accountable to its own people, which opens the door to the country’s ruling elite to become more corrupt and more authoritarian over time. Which is exactly what ended up happening in Venezuela.

Venezuela became one of the founding members of OPEC alongside Saudi Arabia. While the oil prices were roaring, the Venezuelan government decided to nationalize their oil industry and established a new state-owned oil company called PDVSA that would monopolize all of the exploring, drilling, production, refining, and exports in the country. Foreign oil companies were still allowed to continue operating in Venezuela after 1976, but they could only do so under a joint venture with PDVSA, and PDVSA had to own a minimum 60% stake in the joint venture. But, as is well known in the oil industry, prices never remain high forever, and for every boom time, there’s a bust time that always follows. In the 1980s, the global price of oil crashed, and so too did Venezuela’s undiversified government revenues. Inflation in the country accelerated, but the government continued taking on huge amounts of debt by continuing to spend aggressively, most notably with their purchase of half of the American oil and gas company Citgo in 1986, and then the purchase of the remaining half of the company four years later in 1990.

Venezuela’s purchase of Citgo was strategic for multiple reasons, though. Venezuela’s oil reserves, while being the largest in the world, are also among the lowest quality in the world. Venezuela’s oil is extremely heavy and crude, full of impurities like sulfur and mercury that require a lot of technical expertise to drill out of the ground. And then, it requires a much more intensive refining process to transform into usable finished end products like gasoline. This is in stark contrast to the oil fields of Saudi Arabia. Saudi oil is slightly smaller in volume compared to Venezuela’s, but it is lighter and purer, making it easier and cheaper to drill and refine. This has contributed to Saudi Arabia becoming the world’s most influential oil power and Venezuela a mere secondary player.

History of Venezuela’s Oil Economy | 0:15:20-0:23:40

Across the 1980s, American oil refineries across the Gulf Coast and Texas and Louisiana began anticipating that the world was starting to run out of the lighter, more pure crude oil deposits that were easy to refine, and as a result, everyone was eventually going to have to start refining the heavier and less pure crude oil going forward, like the oil that’s found in Venezuela. Consequently, most of America’s Gulf Coast refineries began retooling themselves to handle the world’s heavier and less pure oil, and they became some of the only refineries in the world that could actually handle the processing required of Venezuela’s extra-heavy crude oil.

Venezuela’s geographic proximity to oil fields made it logical for them to use refineries in the US, like Citgo, to refine and sell oil to American consumers. By 1997, Venezuela was America’s largest oil source, but corruption within the Venezuelan government was rampant. In 1989, Venezuela sought a bailout from the IMF, leading to austerity measures and deadly riots. In 1992, Hugo Chavez attempted a coup, failed, and was imprisoned. After his release in 1994, Chavez ran for president in 1998.

Chavez ran under a socialist campaign in Venezuela, promising to distribute the country’s oil wealth more equitably to the poor and end corruption. He was voted into power in 1998 and expanded his office’s powers with little opposition. Independent media outlets were shut down, press freedoms decreased, and presidential term limits were abolished. Chavez also increased his party’s control over the national oil industry by seizing oil projects jointly owned with American companies like Exxon and ConocoPhillips.

Chavez fired thousands of experienced PDVSA employees during a strike in 2002–2003, replacing them with inexperienced loyalists, leading to a decline in Venezuela’s oil production. Venezuela sold oil at a discount to friendly nations like Cuba and Nicaragua, while aligning foreign policy with Russia and China. The administration purchased $20 billion worth of arms from Russia, further impacting the country’s economy.

Venezuela’s relationship with Russia included the acquisition of Russian fighter jets, surface-to-air missile systems, and tanks in exchange for partnerships in Venezuelan oil fields and loans. The shift towards Russia led to an arms embargo from the US in 2006. As oil production declined under Chavez, Venezuela’s oil exports to the US decreased, with Canadian crude oil replacing Venezuelan oil in American refineries. Chavez’s government spending and deficits increased Venezuela’s national debt, which became unsustainable as oil prices fell.

Venezuela’s Current Situation | 0:23:40-0:30:00

Maduro’s regime also witnessed a decline in press freedoms, with Venezuela’s economy heavily reliant on the oil industry. Venezuela’s current situation is dire, with the country ranking in the bottom 20 globally alongside Russia and Belarus. Most television channels are state-owned, and the government’s violence against its people has escalated, leading to over 20,000 extrajudicial killings. The economic crisis worsened after the 2014 oil price drop and continued mismanagement. Maduro’s disputed re-election in 2018 was widely criticized as fraudulent, leading to international rejection of the results.

After the 2018 election, only a few countries like Cuba, Bolivia, Russia, Syria, Iran, China, and North Korea continued to recognize Maduro’s leadership in Venezuela. The United States, along with other countries, refused to recognize Maduro and imposed severe sanctions on his government and the state-owned oil company PDVSA to pressure him to step down. These sanctions included a ban on American imports of Venezuelan oil and cutting off the Venezuelan government from the US financial system starting from January 1st, 2019.

Between 2013 and 2021, the Venezuelan economy experienced a severe crash, with the GDP plummeting by over 75% due to factors like the presidency of Maduro, the COVID-19 pandemic, and hyperinflation. The inflation rate soared to millions of percent in 2018, leading to a practically worthless currency. Poverty rates doubled, with nearly two-thirds of Venezuelans living in poverty by 2021. The economic collapse led to a mass exodus of Venezuelans, with one in four leaving the country by 2023, causing a brain drain issue. Additionally, Venezuela faced restrictions in the American financial system and lost access to exporting oil to the US.

Venezuela lost its ability to send its oil to the vital Gulf Coast refineries that it needed to refine its oil into finished products, including the three Gulf Coast refineries it owned by proxy through CITGO. This occurred as Venezuela’s own oil industry and refineries began languishing under the stresses of fleeing experienced workers and a critical lack of investments and capital necessary for upkeep and maintenance. As a result, Venezuela’s oil production levels have also crashed alongside its economy, with production collapsing from about 3 million barrels per day in 2013, right when Maduro first assumed office, to only about 700,000 barrels a day by the beginning of 2023. This has only compounded Venezuela’s financial problems even further. Now, at the end of 2023 and beginning of 2024, the Venezuelan GDP is only about $92 billion, but the government’s debt is still more than $147 billion, representing a total debt-to-GDP ratio of about 160%.

The nation’s GDP per capita sits at just $3,420, and is ranked in the bottom 5 of the Western Hemisphere and the lowest in the whole South American continent. The unemployment rate is still more than 35% of the country’s remaining labor force, while the population has plummeted to only about 26.5 million people, more than 4 million fewer than they had just a few years ago when they were in the status of a producer that they once enjoyed a century ago. At about the same time as Venezuela’s entire civilization, economy, and oil industry began collapsing from 2015 onwards, plucky little Guyana’s oil industry right next door began booming with the offshore discoveries made by the ExxonMobil-led consortium beginning in 2015.

In an extremely ironic twist of circumstances, Venezuela became the world’s fastest-crashing economy at the exact same time that Guyana right next door became the world’s fastest-growing economy. And in both circumstances, it had to do with oil. But, as it turned out, Guyana’s massive oil discoveries were being made within a maritime region, an extension of a land area in the country that Venezuela had long claimed for itself dating back to the 19th century, the Essequibo region. The origin of the dispute over this area representing two-thirds of Guyana’s current territory goes back to the competing colonial claims of the Spanish and British Empires in South America.

Venezuela’s Territorial Claim Against the British | 0:30:00-0:37:20

Venezuela inherited a territorial claim against the British to the west bank of the Essequibo River from Spain. They began claiming the modern region of Essequibo between the river and their own territory. In 1887, Venezuela severed relations with the UK over this dispute. In 1897, both countries agreed to pass the Essequibo dispute to an international tribunal in Paris, with Venezuela’s interests represented by the United States during the tribunal.

The jurists who would ultimately decide the case came from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia. None came directly from Venezuela. Two years later, in 1899, the Paris Tribunal announced its final verdict. Britain would receive 90% of the disputed land in question, while Venezuela received the remaining 10%. At the time, both Venezuela and the UK accepted these findings as legally binding, in addition to the entire international community, and the case was closed. And that remained the case largely without issue for more than 60 years until the 1960s, when the Essequibo issue came up yet again. As the UK was preparing to finally grant British Guyanese citizenship on their independence in 1966, Guyana inherited the dispute on their end from the British, while Guyana has continued asserting that the findings of the 1899 tribunal are final and binding. From there, the dispute on the region remained open and unresolved, with neither side agreeing to forfeit their claim to it all the way up until 2018 when, after decades of zero progress being made, the matter was finally forwarded to the International Court of Justice in 2018 for yet another international arbitration where it continues to remain today.

But Maduro’s Venezuela rejects the International Court of Justice’s jurisdiction in their country, and as a result, they refuse to ever participate in this most recent arbitration case, and they will almost certainly refuse to recognize whatever final verdict they eventually come up with. And then, of course, the nearly two-century-old Essequibo territorial dispute became way, way more important in 2015 when an Exxon-led consortium discovered half a trillion dollars worth of recoverable oil reserves in Guyana, leading to a potential annexation by Venezuela. Venezuela aims to control the Essequibo region to expand its exclusive economic zone and access lighter, easier-to-drill oil. Despite challenges in refining and expertise, Venezuela seeks to exploit the offshore oil fields. With a larger population and military, Venezuela could overpower Guyana in a conflict over the disputed territory.

If Guyana were to try to man the entire border evenly, they would only be able to deploy about 5 or 6 soldiers per kilometer of length. They only have a few dozen old, outdated Soviet-era artillery pieces, no tanks, no armored vehicles, and virtually no navy or air force. By comparison, Venezuela has a standing army of 138,000 active-duty personnel, 30,000 additional reservists, and an estimated 1.6 million paramilitary forces that the Maduro regime controls. An invasion of Guyana to secure the Essequibo region through force would almost certainly not be limited to a mere one-on-one fight. The United States would almost certainly militarily respond against Venezuela for multiple reasons. First, ExxonMobil and now Chevron have invested tens of billions of dollars into developing Guyana’s offshore oil fields since And a Venezuelan assault on Guyana and seizure of the Essequibo would mean that all of those investments would basically just go up in smoke, which alone would place enormous pressure on Washington to ensure that never happens.

But, perhaps more importantly, Guyana is already sending most of its crude oil exports to the European Union and the US West Coast. And, within the next three years, Guyana is expected to more than triple its oil production levels from today. This represents what is almost certainly the largest incoming supply of oil onto the global market in the years ahead. Most of which will go towards the European Union and further assist them in diversifying away from Russia’s oil. And, which will create downward pressures on global oil prices and downward pressures on global inflation. Two outcomes that the United States very much wants to happen. Both to hurt Russia’s war machine in Ukraine and to reduce inflationary pressures being felt at home. If Venezuelan troops were to suddenly roll into the Essequibo region, they would likely meet little resistance from Guyana and swiftly occupy it.

Maduro’s Strategic Moves in 2023–2024 | 0:37:20-0:43:40

Maduro is likely raising the stakes of the Essequibo issue now at the end of 2023 and beginning of 2024 for multiple reasons. There is, of course, all that sweet oil in Guyana’s offshore that’s at play. But there are other factors going on too. He might not actually be serious about ordering an invasion to seize a Florida-sized chunk of land in Guyana that would likely trigger a cataclysmic war. Instead, he might just be simply trying to drum up patriotism in Venezuela to shore up some support for his deeply unpopular regime ahead of the 2024 presidential election. According to a Caracas-based consulting firm called Consultores Ventillistas, Maduro’s approval rating in the country is currently hovering at only about 29%, which is perhaps understandable for the leader who has overseen the world’s greatest economic collapse in recent history. Maduro must know that he’s an unpopular leader, which is why he resorted to fraud and repression during the 2018 election to keep himself in power. It was unprecedented for him to work with the United States to start removing some of their sanctions on his country’s oil industry so that they could begin rebuilding and making more money again. Across 2022 and 2023, he was actually seeing some progress being made on these goals. After the Russians invaded Ukraine and they and the Saudis began a campaign of coordinating oil production cuts, the price of oil momentarily skyrocketed around the world, and Washington suddenly became interested in getting as much oil back onto the global market as possible to begin cooling prices back down and pushing back against Russia. Even if some of that oil had to come from Maduro’s Venezuela. And so, in November of 2022, the Biden administration in Washington eased some of the sanctions that went into force on Venezuela back in 2019, finally enabling Chevron to restart their jointly owned ventures with PDVSA in the country.

In January of 2023, after four years of a complete American embargo on Venezuelan oil imports, small amounts of Venezuelan crude finally began trickling back into the still Venezuelan-owned Citgo refinery on the American Gulf Coast. And then, on the 18th of October 2023, the United States agreed to effectively lift all of their sanctions on the Venezuelan oil industry for a period of six months, in exchange for Maduro agreeing to free political prisoners and agreeing to host genuinely open and free presidential elections in 2024. And then, knowing, or perhaps realizing, that he would almost certainly lose a genuinely open and free election in 2024, he has perhaps decided on a strategy of hyping up the Essequibo issue with Guyana now to try and increase patriotic sentiment for his struggling poll numbers. But then, by doing this and demanding two-thirds of a neighboring oil-rich country, with tens of billions of dollars worth of private US investments sunk into it, he’s just gone and made himself a pariah to the United States all over again.

If he escalates the rhetoric over Essequibo and the maps showing Essequibo as a part of Venezuela and sends in the army to actually enforce it on the ground, then any future hope of sanctions relief on his country’s already floundering oil industry will immediately evaporate so long as he continues to remain in power, and any hope of Venezuela recovering with him at the helm will be destroyed for good. And that’s assuming the United States wouldn’t just respond with a second Gulf War aimed at obliterating his regime from the face of the earth, which they probably would. It seems so insane for Maduro to continue considering an invasion of Guyana that it won’t ever actually happen. But, just because something doesn’t make any sense to you or me doesn’t mean that it won’t actually happen.

Consider something that happened back in 1982. Back then, Argentina was ruled by an unpopular military junta that was struggling to hold on to power in the country. Their idea to continue hanging on to power was to whip up a sense of patriotism by enforcing one of Argentina’s long-standing territorial claims on the nearby Falkland Islands administered by Britain. A territory that they called the Islas Malvinas, and something that they had claimed to have been stolen from them by the British during the age of colonialism. Home to nothing other than 1,800 people and 400,000 sheep, the Argentines launched a surprise scale amphibious invasion of the islands and secured total control over them with little resistance in less than 24 hours of landing. They expected that the British, nearly 9,000 miles away on the other side of the world, would do nothing. The islands would become theirs, and the act of securing the islands after more than a century of dispute would solidify their struggling regime’s legitimacy and popularity, and enable them to continue staying in power. But they grossly miscalculated. Instead, the British sent down an armada to fight them and a ten-week-long war exploded between them. Hundreds of soldiers on both sides were killed and thousands were injured. Major ships were sunk, and dozens of aircraft were shot down. More people were killed and wounded over the fighting for the Falkland Islands in 1982 than people who actually lived there. In the end, the British emerged victorious. The Argentine invasion was decisively defeated, and the already unpopular military junta in the country collapsed under the scale of the disaster.

Hardly anybody believed in early February of 2022 that the Russians were imminently about to invade Ukraine. Ukraine, despite all of the warnings and the posturing because it didn’t seem to make sense to Westerners for them to actually do it. But here we are, nearly two years later and hundreds of thousands of deaths later, with the war in Ukraine still raging on. Perhaps Maduro might believe that with the United States presently distracted with major ongoing wars in Ukraine and around Israel, Washington would be less interested or even less capable in also intervening against a Venezuelan seizure of the Essequibo region now. And by doing that and being successful at it, it would finally resolve a centuries-old territorial dispute in Venezuela’s favor, make it appear as if Maduro was standing up to the global colonial powers, solidify his unpopular regime’s legitimacy, and popularity in the process, and enable him to continue holding on to power. He might also be only seeking to simply use the threat of war to gain more leverage during his own negotiations with the United States on further sanctions relief on his country’s oil industry. He must know that Washington won’t want another war breaking out in their own backyard with the current one still raging in Ukraine and around Israel.